In what follows I will try to offer a literary alternative to the murderous, supersessionist versions of the story that animates the site. The textual and the physical sites that appear so recalcitrant and exclusive are actually interwoven, more elastic and artificially constructed than they appear in contemporary theological or political discourse. So if we can solve the textual conundrum, we may be able to resolve the conflict on the ground.

The site of revelation and sacrifice begins in the Hebrew Bible with the vague injunction to Abraham in Genesis 22.2 to “go forth to the land of Moriah and offer [Isaac] up as a burnt offering on one of the mountains which I shall say to you.”5 It then moves through a number of extemporaneous altars and dramatic encounters to a movable ark accompanying a people in the wilderness and, finally, to one fixed shrine in Jerusalem. But even after King David has consolidated his dominion over Jerusalem and established its status as sacred center by bringing the Ark of the Covenant to the city, and even as his son Solomon commences building a “house” for the Lord, there remains some ambivalence about confining the divine into one physical space. It emerges that the holiest place in Judaism is not the dwelling place of the deity but the site where the human voice can call to, can name, can invoke, the deity. God repeatedly refers to “this house, which is called by my name,” not the place where God dwells (1 Kings 8.15–19; Jer. 7.11, 13–14).6

That is, this bold monotheistic move, by which the presence of the divine is established, is one of appellation, a human speech act—undermined periodically, however, when people attempt to reify the desire to draw near to, to possess, or to merge with the divine.7 The seesaw between unmediated presence and forms of mediation—calling, naming, imagining—will continue to haunt and shape Judaism from its inception in ancient Hebrew impulses to the present.8 After the destruction of the First Temple by the Babylonians in the sixth century BCE, before the dust had settled on its ruins, before physical reconstruction had commenced under the new Persian regime, it was rebuilt as a vision or figment of the imagination—in the prophecies of both Ezekiel and Zachariah.9

But the pendulum continues to swing. The Hebrew Bible, which opened in Genesis with a vague designation of “one of the mountains [in the land of Moriah],” concludes with a reference in 2 Chronicles to Solomon’s building the “house of the Lord” on “Mount Moriah, where the Lord appeared to David his father” (3.1). And thus the mountain has been known ever since: all the shrines and hills consolidated into one spot,10 all the holiness and all the squabbling stories and stones, like the squabbling brothers, concentrated in a few dozen acres.11

My argument is that the symbolic status of the city—a wandering signifier—was born at the same time as the material edifices. And that the topocentric need for what Mircea Eliade would have called an axis mundi continues to compete with more spacious, inclusive, and self-conscious linguistic and ethical flexibilities hidden in plain view in the constitutive text.

I entitled my remarks “Literary Archaeology at the Temple Mount.” Archaeologists tend to find what they are looking for, and current archaeology of the area around the Temple Mount is governed by those who discard evidence in which they are not invested. Although physical remains of the reign of David are virtually nonexistent, Elad, the right-wing Israeli group in charge of much of the reconstruction of the so-called City of David, creates what is meant to be an authentic evocation of the past through visual and textual means; these architectural “reconstructions” and “archaic” landscapes succeed in eradicating or occluding almost all traces of Islam or Arabs, past or present.12

Literary archaeology has the advantage of keeping your hands clean, even while you are paging through a text that is thousands of years old. It can, like later appropriations in the midrash and in other monotheistic traditions, be twisted or squeezed to yield various versions and meanings, but the text itself is always there to be rediscovered. A literal reading of the story will highlight certain structural and narrative quirks that determine the genre and contain the secret of the akeda.

Genesis 22 begins very theatrically, like the Book of Job: “And it happened after these things that God tested Abraham.” This is a wink behind Abe’s back to the audience, who is given some assurance that the old man will pass the test. In what follows we may be forgiven if we forget the stage wink as we get caught up in the unfolding tragedy. J. William Whedbee, in his study The Bible and the Comic Vision, follows Northrop Frye in calling the U-shaped plot pattern the telltale curve of the comic. According to Frye, this pattern entails “action sinking into deep and often potentially tragic complications, and then suddenly turning upward into a happy ending” (qtd. in Whedbee 7).13 Disaster averted at the last minute through divine intervention is the Hebrew version of deus ex machina.

The structural seemingly needs no elaboration. We all know that Genesis 22 ends with Isaac’s release, yet we repeatedly repress that knowledge so that Isaac can continue to animate our tragic imagination. From the description of Isaac’s “death” and “resurrection” in the midrash14 through nearly every modern Israeli version—and through all its appropriations in Christian iconography—the akeda is apprehended as an accomplished sacrifice. In fact, the occlusion of the happy ending in Genesis 22 is fundamental to the evolution of the genre of tragedy as sacrifice; safeguarding the place of the sacrificed son, the pharmakos—Isaac or Jesus—is tantamount to safeguarding the very “idea of the tragic,” as Terry Eagleton argues in Sweet Violence. So unearthing the comic structure in the place of ultimate sacrifice becomes a subversive act.

The other element that signals the comic in this narrative cycle is rhetorical or linguistic: the repetitions and wordplays that create literary patterns in the Bible. Genesis 17.17 is the first time the word z-h-k (“to laugh”) is introduced in the six chapters that surround the story of the akeda, when God tells Abraham that his wife, Sarah, will bear a child: “And Abraham flung himself on his face and he laughed [va-yitzhak], saying to himself, ‘To a hundred-year-old will a child be born, will ninety-year-old Sarah give birth?’” In the commentary to his translation of Genesis, Robert Alter notes that “in the subsequent chapters, the narrative will ring the changes on this Hebrew verb, the meanings of which include joyous laughter, bitter laughter, mockery, and sexual dalliance” (83). In short, all the elements of the comic genre. Actually, some version of the word z-h-k appears twenty times in these chapters. Everyone laughs—Abraham, Sarah, Ishmael, and, as a capstone, laughter is embedded in Isaac’s very name, Yitzhak, which means “he will laugh.”

In this most serious of texts the comic muscle is flexed, then, in its every permutation.15 I will illustrate with only one more passage, which replicates Abraham’s response—this time as slapstick or shtick. When Sarah, who is listening at the tent entrance, hears the annunciation given again to her husband, she repeats Abraham’s response: “So Sarah laughed inwardly, saying, ‘After being shriveled, shall I have pleasure, and my husband is old?’ Then the Lord says to Abraham, ‘Why is it that Sarah laughed [lama ze tzahakah Sara], saying, ‘Shall I give birth, old as I am?’ Is anything beyond the LORD?’. . . And Sarah dissembled, saying, ‘I did not laugh [lo tzahakti],’ for she was afraid. And He said, ‘Yes, you did laugh [lo ki tzahakt]’” (Gen. 18.12–15).

Although one can really ham this passage up, in the manner of domestic farce,16 something very consequential is transpiring here. I see this as the beginning of the Jewish version of the Divine Comedy17 as it is passed down from the biblical narrative in Genesis to Philip Roth’s story “Conversion of the Jews.” The exchange manifested hilariously in Sarah’s incredulous laughter, and God’s put-down, actually points to a disparity that will remain fundamental to the Jewish conception of the comic: despite the miracles that are regularly performed throughout the five books of Moses, especially in Genesis and Exodus, there is a healthy Jewish suspicion about any supernatural intervention that disrupts the normal processes of nature. God may be all-powerful, but parturition on the part of a ninety-year-old woman raises the same skepticism as Immaculate Conception will over a thousand years later.

Nevertheless, the laughter intensifies, darkens, and then fades as the story proceeds. After the twenty wordplays on his name, Isaac’s laughter disappears altogether, as if his near-death experience effaced whatever good humor he had.18 Posttraumatic stress disorder is, after all, a far more powerful reflex than humor.

But one can conclude from the convoluted ways in which the biblical story plays out here, and in future histories,19 that the very essence of Yitzhak’s name is manifest in the test that Abraham, and his descendants, actually failed: what was at stake was belief in a God who would desire child sacrifice, or for that matter, any human sacrifice. No, the story states simply, God—the tarrying deus ex machina—would actually prefer the comic version of human history and human-divine relations. Der Mensch tracht, und Gott lacht (man proposes, God disposes [literally, man schemes, God laughs]).

In other words, like the messianic faith in Judaism that posits the inevitability of salvation but also its endless deferral, this constitutive story authorizes the Jewish comedy.20 But today in the Holy Land, where hard-won lessons have again been superseded by sacred temptations and messianic impatience, we need something more radical. The comedy I am endorsing makes more room for human intervention. Grounded in faith but driven by human agency, it has been most powerfully articulated in the bloody twentieth century in the work of Franz Kafka and the ethics of Jacques Derrida. Here is a taste of Kafka’s Abraham:

I would conceive of another Abraham for myself—he certainly would have never gotten to be a patriarch or even an old-clothes dealer—who was prepared to satisfy the demand for a sacrifice immediately . . . but was unable to bring it off because he could not get away, being indispensable; the household needed him, there was perpetually something or other to put in order, the house was never ready. . . . (172)21

Kafka’s Abraham, humbly anti-Kierkegaardian, is the ultimate comic figure, one who cannot obey the call-from-without because he is too embedded and obligated in this world.

The problem is that the “event” of the akeda, enshrined as memory, is what leads us, again and again, to the suspension of ethical obligation and the comic point of view in favor of the tragic-sacrificial mind-set. “Memory serves tragedy,” writes Carey Perloff in the October 2014 issue of PMLA, devoted to tragedy: “In the Sophoclean universe, to hold the memory of an injustice in one’s ongoing consciousness is a heroic act. In today’s world, it can be a form of psychosis” (833).22

The “sacrifice” of Isaac moves, then, from a remembered “event” to an existential posture. Psychotic memory abolishes the wedge that distance and deferral provided. “[The] secret of the sacrifice of Isaac,” Derrida tells us, is the “space separating or associating the fire of the family hearth and the fire of the sacrificial holocaust” (88). (The “whole-burnt offering” that Abraham was to offer in the form of his son is called olah in Hebrew—holocaustum in the Latin Vulgate.) Negotiating that space, between the family hearth—the Kafka/Derrida quotidian—and the fire of the sacrifice, is, then, the forgotten secret.

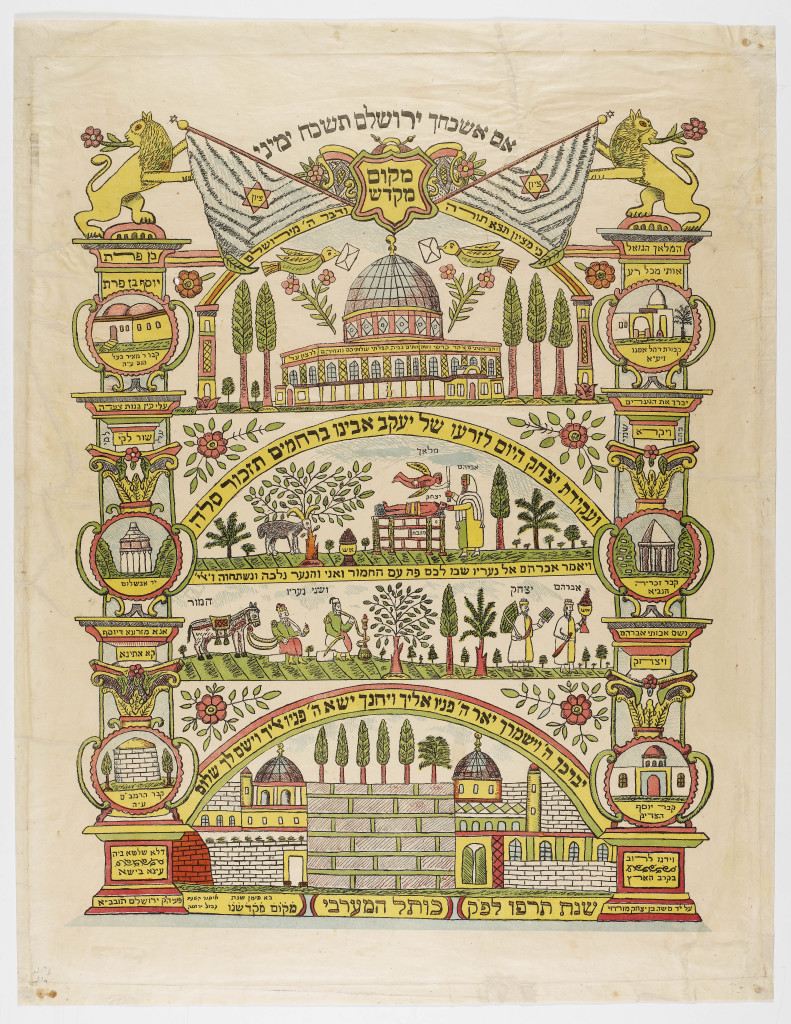

In modern Israel and Palestine, that secret has undergone different iterations and subversions. In the early prestate Jewish community referred to in Zionist memory as the Yishuv, the Temple Mount had more or less the same status in Jewish imagination as it had in the diaspora—although in Jerusalem much of the tension in the 1920s between Muslims and Jews centered on the Wailing Wall, or Al Buraq, and the Temple Mount, or Haram al Sharif.23 The folk art of the period speaks volumes. Consider, for example, a Rosh Hashanah (New Year’s) greeting from 1925 by the craftsman Moshe Mizrahi (fig. 1).24

The iconography is layered and eclectic, representing a popular concatenation of visions for the future. The flag on the top of a somewhat stylized Dome of the Rock says, “mekom ha-mikdash,” or “place of the Temple.” There are a number of biblical verses, including a reference to the akeda and the priestly blessing. There are doves of peace with greetings in their beaks. But the most interesting element is the barely decipherable writing on the mosque meant, presumably, to be the place holder for the Temple. The passage is from Isaiah’s eschatological projections—when God, the speaker, “will bring them to My holy mountain and make them joyful in My house of prayer. Their burnt offerings and their sacrifices shall be accepted on My altar; for My house shall be called a house of prayer for all the peoples” (Isa. 56.7). The reference is to “all the peoples” who accept God’s dominion in the end of days, but the phrase “all the peoples [or nations]” doesn’t appear in the inscription on this card. Naturally, the Hebrew reference to sacrifices and burnt offerings was not exactly pleasing to the Muslims whose Koranic inscriptions it supplants. Although in the ongoing conflict over the Temple Mount this image and others like it enraged the Muslim community—and, as Hillel Cohen shows in his recent study, this kind of supersessionist ambition actually contributed to the riots of 1929 (106–96)—one can also see such acts as at least on some level evoking an “end of days” scenario in which all competing religious visions will be reconciled.25

Because this site was occluded from view and inaccessible to Israelis, because there really was space between the family hearth and the fire of the sacrifice, the Temple Mount was overshadowed by other physical shrines that constituted the “official” Israeli landscape after the establishment of the state in 1948: Yad Vashem and Mount Herzl as memorial sites, the Knesset as the site of modern Jewish sovereignty, and the Israel Museum as a shrine to ancient and modern art.26 Since the Israeli victory of 1967, however, as messianic fervor has grown, all memorial and sacramental activity has converged on the Wailing Wall, with the Temple Mount as site of ultimate aspiration. Along with our loss of boundaries, that is, there has also been the loss of space between us and the sacred center—and, crucially, the loss of our sense of humor.

I suggest, then, an alternative that has always been there, that is consistent with a literal, even “fundamentalist” reading of Genesis 17–22 and of the memory site it animates: a spacious, comic negotiation between the material and the divine, with faith in, but without the hope of, final resolution.

In a speech before the United States Congress in 1994, Jordan’s King Hussein declared, “My religious faith demands that sovereignty over the holy places in Jerusalem reside with God and God alone . . .” (qtd. in Molinaro 17).27 The smiles I imagine on congress members’ faces at the king’s appeal to divine intervention to pacify the squabbling sons of Abraham are the rare signs of our stubborn faith—tested regularly by events on the ground—that politics, like poetry, can be a site where memory yields to magic and comedy defeats tragedy.

Notes

- Israel and Palestine together measure about 10,000 square miles; Massachusetts measures approximately 10,500 square miles. Massachusetts has 6.7 million people; Israel has approximately 6.5 million, and the West Bank and Gaza together just under 4 million (“Israel”).↩

- The reference in the Koran is to the sacrifice of an unspecified son understood by most exegetical traditions to be referring to Ishmael: “And when he reached with him [the age of] exertion, he said, ‘O my son, indeed I have seen in a dream that I [must] sacrifice you, so see what you think.’ He said, ‘O my father, do as you are commanded. You will find me, if Allah wills, of the steadfast.’ And when they had both submitted and he put him down upon his forehead, We called to him, ‘O Abraham, You have fulfilled the vision.’ Indeed, We thus reward the doers of good. Indeed, this was the clear trial. And We ransomed him with a great sacrifice, And We left for him [favorable mention] among later generations: ‘Peace upon Abraham’” (Noble Qu’ran, As-Saffat 102–09). For a comparison of the biblical and the Koranic versions, in which the second incorporates a discussion between Abraham and his “son” and the son’s eagerness to fulfill the sacrifice, see Wikipedia’s entry “Ishmael in Islam,” subsection “The sacrifice.” It should be noted that the midrashic material that elaborates on such a discussion would have been available to the compilers of the Koranic tradition; many scholars of Islam argue that the sources are rabbinic. See Calder. See also Rippin 87 and Caspi and Greene.↩

- For a discussion of the complexities of this phenomenon, see Ma‘oz.↩

- It is not at all clear that pilgrimage to the absent temple is what the biblical redactors had in mind when they legislated the three holidays centered on the Temple of Solomon—and for some two thousand years most Jews found substitutes for cults that were suspended when the Second Temple was destroyed in 70 CE. As for the event on 13 October 2014, strangely, the YouTube videos posted of this clearly choreographed event seem to have been taken down soon afterward. But the potential for apocalyptic violence has not abated. Moshe Feiglin, a stridently anti-Arab Knesset member, was one of those who ascended the Temple Mount. Yehuda Glick, another member of this group, was attacked in west Jerusalem on 24 November 2014 by an assailant who was identified as a militant Palestinian by the Israeli authorities and killed. This was followed a few weeks later by the murder of three Hassidim and a Druze guard in a synagogue in West Jerusalem. During the Passover holiday in April 2016, nearly thirty Jews who tried to pray on the Temple Mount were evicted by police. And so it goes.↩

- Unless otherwise specified, all citations in English of the five books of Moses (Gen.–Deut.) are from Alter; citations from other parts of the Hebrew Bible are from The Jerusalem Bible. I have anglicized the Hebrew transliterations of names used in The Jerusalem Bible.↩

- “The heaven is my throne, and the earth is my footstool: where is the house that you would build for me? And where is the place of my rest?” God says, as ventriloquized by Isaiah, who lived, by textual accounts, in the eighth century BCE but more historically is understood as writing from the Babylonian exile (Isa. 66.1). See on this subject Goldhill 23.↩

- See Maimonides in The Guide of the Perplexed, which considers in some detail the dangers and the attraction of proximity to and anthropomorphic representations of the divine.↩

- On the evolving debate over the specificity of divine presence in the Temple itself, see Hurowitz.↩

- See Mackay; Ezrahi, “‘To What’” 222.↩

- To see how imbricated the history is, consider that the “rock” over which the Dome of the Rock is built, where Mohammed is said to have ascended to heaven, is also identified as the rock where Isaac was nearly sacrificed and as the even ha-shtiya or fundament from which the world was created. Kenan Makiya builds on the traditional view that the mosque was built as a tribute and not just a triumphalist succession to the temple of Solomon. See Ezrahi, “‘To What’” 221; see also 230n5 for a specific engagement with Makiya’s work.↩

- To be more precise, the Old City of Jerusalem measures around 212 acres; the esplanade of Temple Mount—over which the Waqf was granted full civil administrative authority—is approximately 37.1 acres (see Grabar and Kedar, Introduction 9). For an elaboration of the history and ramifications of this site, see A. Cohen; Reiter and Seligman. See also Ben-Arieh 27.↩

- See Greenberg and Mizrachi; Mizrachi. See also the English Web site of Emek Shaveh; Schwartz; and two articles by Tomer Persico on the Temple Mount in Haaretz after the October (2014) skirmish: “Why Rebuilding the Temple Would Be the End of Judaism as We Know It” and “The Temple Mount and the End of Zionism.”↩

- The original quotation comes from Northrop Frye’s Fables of Identity: Studies in Poetic Mythology, page 25. For other related discussions of the comic and its relation to the tragic in classical Jewish sources, see Ezrahi, “After Such Knowledge” and “From Auschwitz.”↩

- “Isaac’s ashes as it were” appears in Ta‘anit 16a; Lev. Rabbah 36.5. On this reference, see Yuval 94. For an elaboration of Isaac and the reverberations of the story of the akeda, see Levenson 192–99.↩

- For a bibliography and references to instances of laughter connected to Isaac’s life, see Zucker.↩

- Whedbee says this is “farce befitting domestic comedy” (76).↩

- The Israeli writer Meir Shalev says that the incredulous laughter of Sarah and Abraham is the first—and also the last—laughter in the Bible. I do not agree that it is the last, but certainly laughter is the dominant motif in the narrative we are looking at. It is, says Shalev, also the first instance of “Jewish humor”—i.e., humor born of danger (213).↩

- The word returns several chapters later, and only when Isaac is described as playing with or fondling his wife, Rebecca, whom he is trying to pass off to Philistine King Abimelech as his “sister” (once again the reference to laughter here suggests sexual dalliance): “ve-hineh yitzhak mitzahek et rivkah ishto” [“Abimelech king of the Philistines looked out the window and saw—and there was Isaac playing with Rebekah his wife”] (Gen. 26.8).↩

- Building on midrashic elaborations on lacunae or inconsistencies in the text, modern scholars see possible traces of a suppressed tragedy—the “actual” sacrifice of Isaac—in the Hebrew Bible itself. See, for example, Fishbane 182.↩

- If the Jews have a credo or a doxology, it is summed up in the following: “I believe in the coming of the Messiah, and even though he tarries, I will wait for him.” See Ezrahi, “After Such Knowledge” and Booking.↩

- See Darrow.↩

- In the Canadian Wajdi Mouawad’s play Scorched, on the civil war in Lebanon, the doctor tells of three young refugees who strayed outside the camps and were hanged by the militia:

Why did the militia hang the three teenagers? Because two refugees from the camp had raped and killed a girl from the village of Kfar Samira. Why did they rape the girl? Because the militia had stoned a family of refugees. Why did the militia stone them? Because the refugees had set fire to a house near the hill where thyme grows. Why did the refugees set fire to the house? To take revenge on the militia who had destroyed a well they had drilled. Why did the militia destroy the well? Because the refugees had burned the crop near the river where the dogs run. Why did they burn the crop? There must be a reason, but that’s as far back as my memory goes . . . but the story can go on forever. . . . (qtd. in Perloff 833)

See, further, Perloff’s discussion of photographs of atrocities in the Middle East, including from Iraq, which prompted her to wonder “how we [might] apply the ethical arguments of Greek tragedy to shed light, for example, on the divisive tribalism of the contemporary Middle East . . .” (831). In this context, where each ethnicity “believes it has the prior claim and the deepest sense of victimization, is the sacrifice of an individual to this cycle of vendetta tragic or foolish? This is the question of the modern Elektra” (832). The question of personal versus “collective tragedy” similarly interests Perloff: “We long for the catharsis of tragedy, for the quest for meaning that defines Greek dramaturgy” (831, 833).↩

- Al Buraq is the Arabic designation of the wall—otherwise known as the Western or the Wailing Wall—where Mohammed was said to have tethered the animal that transported him magically to Jerusalem. On the events leading up to the riots of 1929, see H. Cohen. For a more recent iteration of the ongoing conflict as embedded in naming practices, see UNESCO’s decision in April 2016 to refer to the Wall only as Al Buraq and to the Mount only as Haram al Sharif. And see the response to this decision posted on the Web site Emek Shaveh (Greenberg and Mizrachi).↩

- Moshe Mizrahi—later ben-Yitzhak Mizrahi, still later Sofer—was born in Tehran before 1870 and died in 1940; he is buried on Mount of Olives. My thanks to Eli Osheroff for his stimulating lecture in which he presented this card and its context. The card is the back jacket of the polemic pamphlet by Yehuda Etzion, Alilot ha-mufti ve-ha-doktor [“Plots of the Mufti and the Doctor”]; the “Doctor” referred to is the Zionist leader Haim Arlosoroff. The pamphlet by Etzion is part of the ongoing polemic initiated by Hillel Cohen’s thorough investigation of the events of 1929.↩

- For a fascinating study of the intersections of Jewish and Muslim iconography at, in, and on the Dome of the Rock, see Berger.↩

- Mount Herzl is the military cemetery, which contains rows of identical graves of the young soldiers who gave up their lives for this country; Yad Vashem, the memorial to the dead in the Holocaust, is perched on a hilltop that occludes the hardly visible traces of the Arab village of Deir Yassin in the valley below, many of whose inhabitants were massacred in 1948. One guide at Yad Vashem lost his job because he pointed this out to a group of Israeli soldiers. The other urban centers that defined Israeli sovereignty in Jerusalem—from Yad Vashem to Mount Herzl to the Knesset and government center—eventually gave way to the prominence of religious claims over the sacred center in the Old City. Projection backward to original claims is matched by projection forward to a vision of redeemed Jerusalem, replete with a rebuilt Third Temple meant to usher in the messianic era.↩

- Many of the studies of conflicting claims to contemporary Jerusalem are based on the thorough work of Menachem Klein; see his Jerusalem: The Contested City.↩

Works Cited

Alter, Robert. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary. W. W. Norton, 2004.

Ben-Arieh, Yehoshua. Ir Be-rei ha-tekufa: Yerushalayim be-meah ha-19 [The City in Its Historical Context: Jerusalem in the Nineteenth Century]. Yad Ben Zvi, 1976.

Berger, Pamela. The Crescent on the Temple: The Dome of the Rock as Image of the Ancient Jewish Sanctuary. Brill, 2012. Studies in Religion and the Arts.

Calder, Norman. “From Midrash to Scripture: The Sacrifice of Isaac in Early Islamic Tradition.” Le Muséon, vol. 101, no. 3-4, 1988, pp. 375–402.

Caspi, Mishael, and John T. Greene, editors. Unbinding the Binding of Isaac. UP of America, 2007.

Cohen, Amnon. “1516–1917: Haram i Şerif, the Temple Mount under Ottoman Rule.” Grabar and Kedar, Where, pp. 210–30.

Cohen, Hillel. Tarpa’t: Shnat ha-efes ba-sikhsukh ha-Yehudi-Aravi [1929: The Zero Hour of the Jewish-Arab Conflict]. Keter Books, 2013.

Darrow, Robert Arnold. “Kierkegaard, Kafka, and the Strength of ‘The Absurd’ in Abraham’s Sacrifice of Isaac.” Electronic Theses and Dissertation Center, Wayne State U, 2005, etd.ohiolink.edu/rws_etd/document/get/wright1133794824/inline.

Derrida, Jacques. The Gift of Death. Translated by David Wills, U of Chicago P, 1995.

Eagleton, Terry. Sweet Violence: The Idea of the Tragic. Blackwell Publishers, 2003.

Etzion, Yehuda. Alilot ha-mufti ve-ha-doktor: Ha-siah ha-Yehudi-Muslimi be-noseh har ha-bayit ‘al reka pera’ot tarpa’t [Plots of the Mufti and the Doctor: The Jewish-Muslim Discourse on the Temple Mount as Background to the Riots of 1929]. Sifriyat Beit El, 2013.

Ezrahi, Sidra DeKoven. “After Such Knowledge, What Laughter?” Interpretation and the Holocaust. Special issue of Yale Journal of Criticism, vol. 14, no. 1, 2001, pp. 287–317.

———. Booking Passage: Exile and Homecoming in the Modern Jewish Imagination. U of California P, 2000.

———. “From Auschwitz to the Temple Mount: Binding and Unbinding the Israeli Narrative.” After Testimony: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Holocaust Narrative. Edited by Susan Suleiman, Jakob Lothe, and James Phelan, Ohio State UP, 2012, pp. 291–313.

———. “‘To What Shall I Compare You?’: Jerusalem as Ground Zero of the Hebrew Imagination.” PMLA, vol. 122, no. 1, Jan. 2007, pp. 220–34.

Fishbane, Michael. Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel. Clarendon Press, 1985.

Frye, Northrop. Fables of Identity: Studies in Poetic Mythology. Harcourt, Brace and World, 1963.

Goldhill, Simon. The Temple of Jerusalem. Harvard UP, 2005. Wonders of the World.

Grabar, Oleg, and Benjamin Z. Kedar. Introduction. Grabar and Kedar, Where, pp. 9–13.

———, editors. Where Heaven and Earth Meet: Jerusalem’s Sacred Esplanade. U of Texas P, 2010. Jamal and Rania Daniel Series.

Greenberg, Rafi, and Yonathan Mizrachi. “Mi-silwan le-har ha-bayit: Hafirot archeologiot ke-emtza’i le-shlita; Hitpathuot—bekfar silwan u-ve-ir ha-atika shel yerushalayim be-shnat 2012” [From Silwan to the Temple Mount: Archaeological Digs as Means of Control; Developments in Silwan and the Old City of Jerusalem in 2012]. Emek Shaveh, alt-arch.org/en/from-silwan-to-temple-mount. Accessed 29 Nov. 2014.

Hurowitz, Victor Avigdor. “Tenth Century BCE to 586 BCE: The House of the Lord (Bayt YHWH).” Grabar and Kedar, Where, pp. 15–34.

“Ishmael in Islam.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 9 Aug. 2015, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishmael_in_Islam.

“Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory” The Carter Center, www.cartercenter.org/countries/israel_and_the_palestinian_territories.html. Accessed 23 Oct. 2014.

The Jerusalem Bible. Koren Publishers, 1992.

Kafka, Franz. “Abraham.” The Basic Kafka. Washington Square Press, 1979, pp. 170–72.

Klein, Menachem. Jerusalem: The Contested City. Hurst, 2001.

Levenson, Jon D. The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son: The Transformation of Child Sacrifice in Judaism and Christianity. Yale UP, 1995.

Mackay, Cameron. “Zechariah in Relation to Ezekiel 40–48.” The Evangelical Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 4, 1968, pp. 197–210. Biblical Studies.org.uk, biblicalstudies.org.uk/pdf/eq/1968-4_197.pdf.

Maimonides, Moses. The Guide of the Perplexed. Translated by Shlomo Pines, introduction by Leo Strauss, 2 vols., U of Chicago P, 1974.

Makiya, Kenan. The Rock: A Tale of Seventh-Century Jerusalem. Vintage, 2002.

Ma‘oz, Moshe, editor. The Meeting of Civilizations: Muslim, Christian, and Jewish. Sussex Academic Press, 2009.

Mizrachi, Yonathan. Letter to the UNESCO executive board. 19 Apr. 2016, http://alt-arch.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Emek-Shavehs-Response-to-UNESCO-Executive-Board-199th-decision.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2016.

Molinaro, Enrico. The Holy Places of Jerusalem in the Middle East Peace Agreements: The Conflict between Global and State Identities. Sussex Academic Press, 2009.

The Noble Qu’ran. www.quran.com. Accessed 12 Nov. 2014.

Perloff, Carey. “Tragedy Today.” PMLA, vol. 129, no. 4, Oct. 2014, pp. 830–33.

Persico, Tomer. “The Temple Mount and the End of Zionism.” Haaretz, 29 Nov. 2014, www.haaretz.com/news/features/.premium-1.628929.

———. “Why Rebuilding the Temple Would Be the End of Judaism as We Know It.” Haaretz, 13 Nov. 2014, www.haaretz.com/news/features/.premium-1.626327.

Reiter, Yitzhak, and Jon Seligman. “1917 to the Present: Al-Haram al-Sharif / Temple Mount (Har ha-Bayit) and the Western Wall.” Grabar and Kedar, Where, pp. 230–73.

Rippin, Andrew, editor. The Qu’ran: Formative Interpretation. Ashgate, 1999.

Schwartz, Hava. “National Symbolic Landscape around the Old City of Jerusalem.” Hebrew U of Jerusalem, 2013.

Shalev, Meir. Reshit: Pe-amim Rishonot Ba-Tanakh [In the Beginning: First Steps in the Bible]. Am Oved Publishers, 2008.

Whedbee, J. William. The Bible and the Comic Vision. Cambridge UP, 1998.

Yuval, Yisrael. “God Will See the Blood: Sin, Punishment, and Atonement in the Jewish-Christian Discourse.” Jewish Blood: Reality and Metaphor in History, Religion and Culture, edited by Mitchell B. Hart, Routledge, 2009, pp. 83–99.

Zucker, David J. “Isaac: A Life of Bitter Laughter.” Jewish Bible Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 2, 2012, pp. 105–10, jbq.jewishbible.org/assets/Uploads/402/jbq_402_isaaclaughter.pdf.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.Posted July 2016