We are entering an era of higher education in which the capacity to adapt matters more than size alone. For faculty members accustomed to thinking that the goal of any major is to grow, and who are convinced that enrollment management is a zero-sum game, a different age has dawned. Bigger is not necessarily better.

Since the 1960s the number of degree programs offered by baccalaureate-granting colleges and universities in the United States has ballooned from under two hundred to over 1,100. More majors has meant, on average, a smaller share of students for each. While a few individual degree programs retain an outsize share, students are mostly spreading out to newer degree programs, some of which have miniscule numbers of graduates.

Language and literature departments interested in creating new majors would be well advised to consider the changing landscape of higher education, in which niche programs are increasing in number. Too much attention is given to the outliers: big majors that keep getting bigger or online programs that enroll thousands. A look across the country reveals a very different and potentially more important trend: growing numbers of interdisciplinary and subdisciplinary majors, as well as small, nondepartmentalized disciplines. This development poses new organizational challenges at the department, college, and university level.

Language and literature departments interested in creating new majors would be well advised to consider the changing landscape of higher education . . .

A close examination of the United States Department of Education’s degree-completion taxonomy and classification of instructional programs can give us a more realistic understanding of current trends in majors in higher education, as well as better tools for cultivating and preserving humanities programs. Analysis of this taxonomy and the data collected by means of it supports our contention that, when it comes to helping the humanities thrive, innovation and collaboration across small programs may be a better strategy than doubling down on a few large disciplines.

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), an office within the Department of Education, records degree completions at colleges and universities across the country using a system called the Classification of Instructional Programs (CIP). As required by the Higher Education Act, colleges and universities report degree completions using standard CIP codes. The Department of Education (DOE) defines an instructional program as a collection of courses or experiences offered by a recognized institution of higher education that lead to a degree or comparable award (“Introduction” 1–2). For nearly a half century, the DOE has given CIP codes to an ever-widening range of programs. The latest revision added a CIP code for Hawaiian Language and Literature and one for Anthrozoology, for example. Changes to the CIP code taxonomy reflect trends in major degree-program offerings and provide the means by which those offerings are reported.

To better understand the structural change in higher education over time, we will delve into the historical development of the CIP code taxonomy, which is often overshadowed by reports about the current state of degree completions. Most of the time we hear about the fate of individual degrees or variously constructed categories like the humanities. One learns that, like stocks on the market, English is down and computer science is up. Buy STEM. Dump your holdings in the humanities. These headlines grab the attention of faculty members who teach in these majors—and may elicit feelings of schadenfreude for others. But they do not tell us anything about the larger framework within which the fate of any particular degree is decided. That framework matters, because it allows us to understand how the fates of humanities majors are shaped by changes in higher education as a whole.

The Degree-Program Explosion

In 1967 the federal government launched the Higher Education General Information Survey (HEGIS), which in its inaugural year recorded degrees awarded in 187 programs of study. Its taxonomic architecture was revamped in 1980 with the introduction of the CIP code scheme, which itself has since undergone a series of updates. In 1992 the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) replaced HEGIS as a means of organizing higher education data, including CIP data.1 As of the 2020 update there are 2,149 distinct CIPs. We estimate that around 1,400 of these CIPs will be offered as four-year degrees.

The growing number of CIP codes is the result of a highly choreographed process of program review involving DC bureaucrats as well as college and university personnel from across the country. NCES collects information from course catalogs provided on college and university Web sites, conducts research, and identifies and reviews potentially new species of degrees (“Introduction” 3). After receiving input and suggestions from stakeholders—state coordinators, for instance—a CIP panel releases a revised scheme to the public for feedback. Once this feedback has been reviewed, the new CIP schema becomes the basis for IPEDS’s reporting on degree completions.

Colleges and universities have some flexibility when deciding how they classify degree programs. Such decisions might well be driven more by institutional program structures than by the CIP scheme. For instance, similar curricula in film and media studies may lead to completions recorded as Mass Communication/Media Studies (CIP code 09.0102), Film/Cinema/Media Studies (50.0601), or even English Languages and Literatures, General (23.0101).2 If film faculty members work in a college of communications, it makes sense to record the completions in Communication, Journalism, and Related Programs (09). It may not make sense to do so, however, if those faculty members are part of a school of arts, which likely houses degrees in Visual and Performing Arts (50). Reporting completions under English, in contrast, would reflect a decision not to award a distinct degree in film and media studies.

In 2020 new CIP codes have been made available as part of the scheme’s revision. A sampling of these codes indicates the range of new offerings (table 1).

| wdt_ID | CIP Code | CIP Title |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 01.0310 | Apiculture |

| 2 | 05.0135 | Appalachian Studies |

| 3 | 09.0909 | Communication Management and Strategic Communications |

| 4 | 11.0902 | Cloud Computing |

| 5 | 13.0413 | Education Entrepreneurship |

| 6 | 15.1704 | Wind Energy Technology/Technician |

| 7 | 26.0509 | Infectious Disease and Global Health |

| 8 | 27.06 | Applied Statistics |

| 9 | 27.0601 | Applied Statistics, General |

| 10 | 30.34 | Anthrozoology |

Table 1. Selected Additions to the 2020 CIP Scheme. Source: Classification of Instructional Programs, 2020 Revision, National Center for Education Statistics, nces.ed.gov/ipeds/cipcode/default.aspx?y=56.

Examples like Anthrozoology, Thanotology, and Data Science demonstrate how the CIP code taxonomy is built, with an initial two-digit number indicating degree-program family, followed by a four-digit number, the first two digits of which indicate the genus and the second two of which indicate species. Since there can be no individual program species without a genus, in some instances both a new genus and a species with the same name will be added at the same time (e.g., Anthrozoology). The 2020 revision shows considerable growth in CIP family number 30, also known as Multi-/Interdisciplinary Studies.

There are various possible reasons for the new CIPs featured in the 2020 revision, especially given the breadth of the taxonomy, which covers all postsecondary degrees, from associate’s to doctoral. Changes in faculty research specialization, response to demand from students, response to demand from a changing national or regional economy, collaboration with local employers, and myriad other explanations might be behind the changes. A closer look at some humanities additions to the 2020 CIP scheme indicates that someone has a stake in developing these fields but does not explain whether those stakeholders are administrators or faculty members working in these fields (table 2).

| wdt_ID | CIP Code | CIP Title |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16.1409 | Hawaiian Language and Literature |

| 2 | 16.1701 | English as a Second Language |

| 3 | 30.3601 | Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature |

| 4 | 30.4001 | Economics and Foreign Language/Literature |

| 5 | 30.4501 | History and Language/Literature |

| 6 | 51.3204 | Medical/Health Humanities |

Table 2. Selected Humanities Additions to the 2020 CIP Scheme. Source: Classification of Instructional Programs, 2020 Revision, National Center for Education Statistics, nces.ed.gov/ipeds/cipcode/default.aspx?y=56.

This is important: the humanities are not balkanized by the CIP scheme but rather infuse the taxonomy in ways that may seem surprising. The scheme’s conceptual arrangement of fields does not correspond to the organizational chart of any institution.

In fact, the CIP might offer a more accurate picture of the history of the academy in the United States than can be gleaned from the various disciplinary histories through which so many of us know higher education’s past. The evolution of the taxonomy highlights cross-pollination and schism, novelty and innovation. In contrast, disciplinary histories tend to tell narratives of rise and inevitable fall.

Consider the degrees nested within CIP family 23, English Language and Literature/Letters. The history of this CIP category offers a snapshot of a disciplinary array that has grown increasingly complex. There were no changes in 2020, but previously the taxonomy was highly unstable, spinning off degrees, generating new ones within English Language and Literature/Letters, and reorganizing those degrees in various configurations (table 2).

Faculty members in English departments may recognize a process whereby some areas of teaching and instruction slowly differentiate themselves and then drift away. For example, in 2010 Rhetoric and Composition/Writing Studies came to name a genus of three different degree programs within English. Previously, those programs may have existed in English but been invisible to IPEDS, or they may have been organized under some other CIP. The same process of differentiation has also affected more explicitly literary programs of study. New degrees like American Literature (United States) as well as Children’s and Adolescent Literature emerged and were rearranged during the period from 1990 to 2010 (see table 3).

| wdt_ID | 2000 Code | 2000 Title | Action | Text Change | 2010 Code | 2010 Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23.01 | English Language and Literature, General | No substantive changes | no | 23.01 | English Language and Literature, General |

| 2 | 23.0101 | English Language and Literature, General | No substantive changes | no | 23.0101 | English Language and Literature, General |

| 3 | 23.04 | English Composition | Deleted | no | 23.04 | Deleted |

| 4 | 23.0401 | English Composition | Deleted | no | 23.0401 | Deleted, report under 23.1301 |

| 5 | 23.05 | Creative Writing | Deleted | no | 23.05 | Deleted |

| 6 | 23.0501 | Creative Writing | Moved to | no | 23.1302 | Creative Writing |

| 7 | 23.07 | American Literature (United States and Canadian) | Deleted | no | 23.07 | Deleted |

| 8 | 23.0701 | American Literature (United States) | Moved to | no | 23.1402 | American Literature (United States) |

| 9 | 23.0702 | American Literature (Canadian) | Moved to | no | 23.1403 | American Literature (Canadian) |

| 10 | 23.08 | English Literature (British and Commonwealth) | Deleted | no | 23.08 | Deleted |

Table 3. English Languages and Literature/Letters (CIP 23), 2000 to 2010 Crosswalk. Source: Classification of Instructional Programs, 2000 to 2010 Crosswalk, National Center for Education Statistics, nces.ed.gov/ipeds/cipcode/Files/Crosswalk2000to2010.csv.

At a time when the broader landscape of higher education is changing, it would be perilous to rely on a singular metric of success.

Creative Writing might appear to be a possible still point in the shifting landscape. It was a degree option in the HEGIS scheme, and it remains one today. However, it has also spawned options in other CIP families, including Visual and Performing Arts (CIP 50), home of Playwriting and Screenwriting (50.0504) as well as Theatre Literature, History and Criticism (50.0505). Likewise, rhetoric has appeared in new locations beyond English, for example, as part of Communication, Journalism, and Related Programs (09).3 Writing instruction also appears in Basic Skills and Developmental/Remedial Education (32). One might be surprised to learn that Comparative Literature, Classics, and Linguistics were grouped with English in the HEGIS taxonomy. All of them had struck out on their own by 2000.

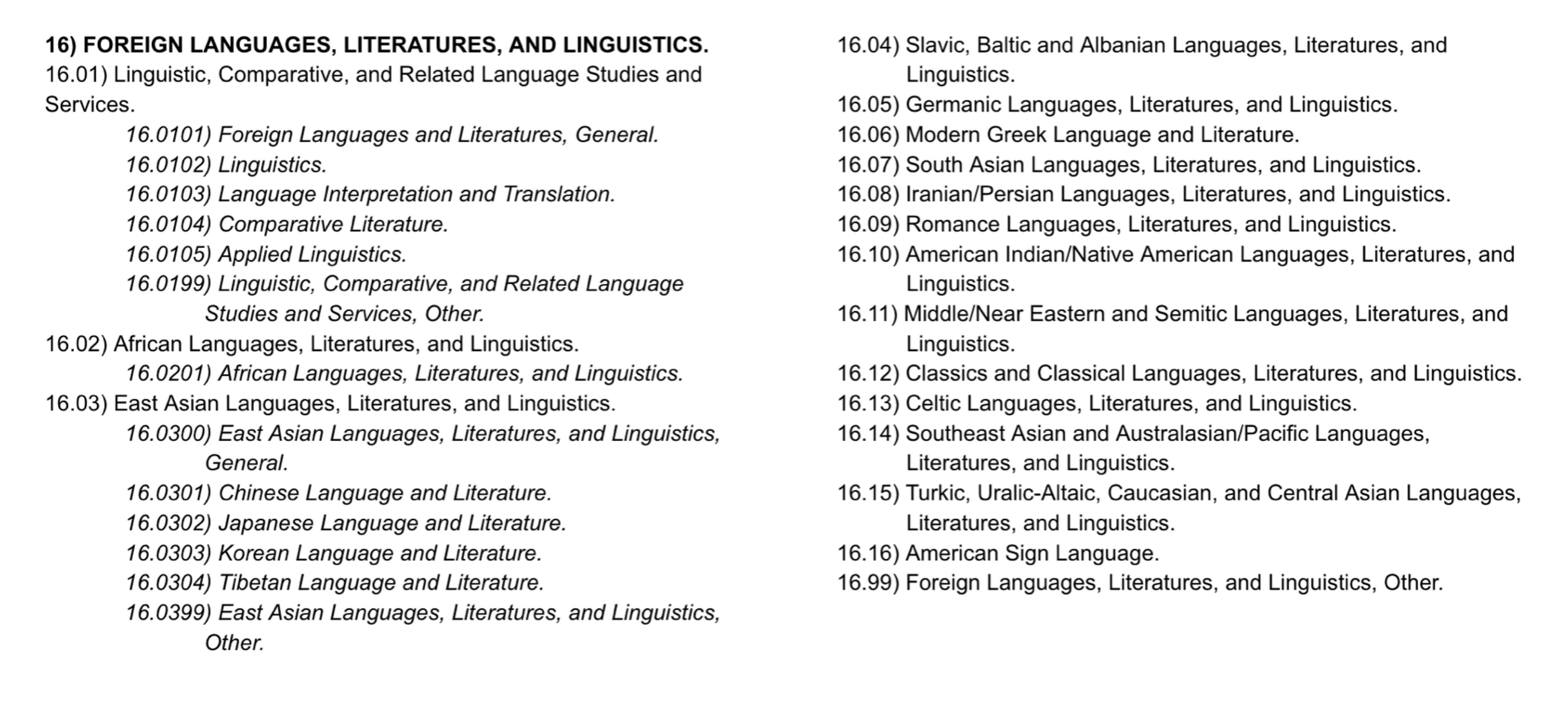

These changes to the scheme make apparent the realignment and dissemination of humanities degrees one might otherwise think of as neatly nested within a select number of traditional families (English, History, etc.). Each CIP revision not only captures a moment amid ongoing instability but also manifests areas of taxonomic coherence. A perfect example of this may be found in Foreign Languages, Literatures, and Linguistics (CIP 16).

Degrees in various languages and literatures nest right where one expects them to within a geographically delimited taxonomy. In the left-hand column of figure 1, expanded genus categories reveal the species within. The genus categories in the right-hand column may also have species under them, although we have not shown them here.

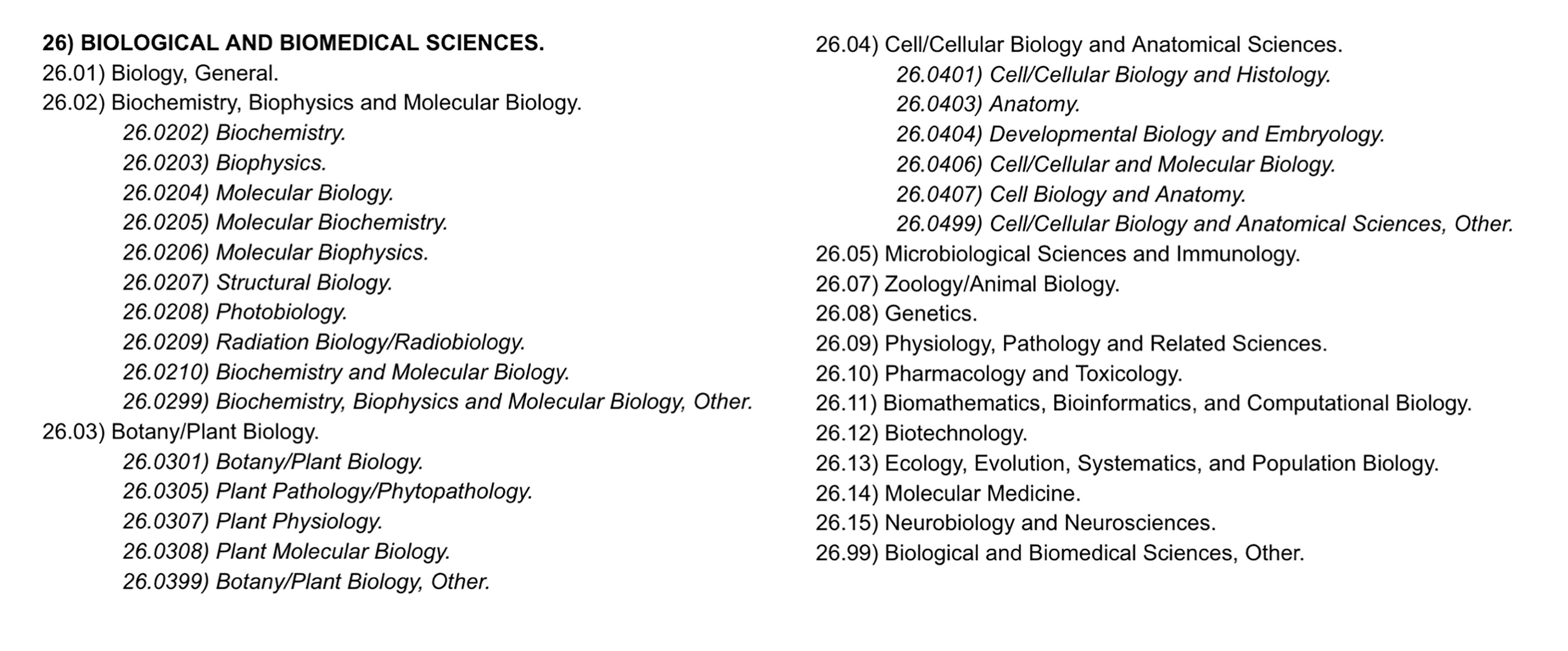

Biological and Biomedical Sciences (CIP 26) presents similarly tidy organization in some areas. At the same time, it includes categories like 26.11 and 26.12, which show the conventional definition of biology stretching to accommodate computational approaches, technology development, and other emphases that had not previously fallen under its purview. The sciences, like the humanities, evolve.

Aggregation Is Always Misleading

The proliferation of new credentials and the drama of defining relations among fields of instruction disappear, however, when CIP data is aggregated. This, unfortunately, is how that data is most typically encountered. We have all seen charts like the one included in Benjamin Schmidt’s 2018 Atlantic essay on the state of humanities majors. Colored lines labeled Religion, History, and English plummet toward the X axis, capturing graphically the fall from grace that dominates in disciplinary histories of humanities fields.

This kind of aggregation makes data recorded through the CIP code scheme intelligible, but it also introduces a misleading narrative. Precisely because it demands that we only see monoliths like “English” rather than the variety apparent within the scheme, such aggregation fails to render the way higher education is changing. As we have shown, humanities degrees show up in parts of the taxonomy where one may not expect to find them—for instance, in Medical Humanities (CIP 51.3204) or any of the multidisciplinary hybrids in CIP 30. The tendency of the humanities, like all disciplines, to cross-pollinate and propagate throughout the scheme cannot be captured by a plunging trend line. No future is anticipated by this kind of chart. Instead, such figures depict a fall from grace, while simultaneously erasing the new terrain created by the explosive growth of degrees.

It is possible to get a sense of what is left out of the plummeting humanities charts by comparing the aggregation scheme employed by the National Science Foundation (NSF) with the method used by the NCES. In NSF publications, including the Survey of Earned Doctorates, a field group called Humanities and arts includes four categories: Foreign languages and literature, History, Letters, and Other humanities and arts (“Technical Notes,” Table A-6). There is more here than meets the eye. No one can earn a degree in Other humanities and arts, of course. That label aggregates some nineteen different degree areas, ranging from Archaeology (which also appears under the aggregation Social Sciences) to Theology/Religious Education (SED). That latter category gets its own data line in the NCES aggregations (Theology and Religious Vocations), which also include lines for English language and literature/letters and the remarkable catchall Liberal arts and sciences, general studies, and humanities (“Table 318.50”). Perceptions of degree share will vary according to which of these competing schemes one follows. Neither the NCES nor the NSF, we stipulate, sets out to deceive its readers. Misprision results from the generic conventions of the share report, where intelligibility demands that the many hundreds of fields in which a college student might actually major be reduced to a few bundles—perhaps as many as fifty if the data is presented in tabular form, far fewer if a pie chart or time-series plot presents it. Representing share in this manner means obfuscating the university’s actual structure.

The Web site of the Humanities Indicators project, run by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, offers a helpful gloss on the challenge of aggregation, maintaining that “[t]he organizations and studies from which indicator data are drawn may include different disciplines within the humanities. For example, some count all theology and ministry courses as humanities instruction; others class history as one of the social sciences; still others assume all general education to be humanistic” (“Context”). The point is not that competing aggregations are wrong but rather that all aggregation is contestable. Aggregation reflects, to put it somewhat differently, the historical debates that have shaped and reshaped definitions of the humanities—and the social sciences, and the sciences.

Most practicing scholars in fields such as English and the languages are aware that the humanities, as a category, has changed over time. We see no reason to rehearse that history here. Neither are we particularly interested in valorizing one of the various present-day norms for including disciplines within, or excluding them from, that category. Instead, in recalling that the humanities are always an aggregation of existing degree programs, and in noting that the pretended clarity of such aggregations is always misleading, we want to make it easier to recognize what IPEDS data reveal by resisting the urge to aggregate.

Disaggregated shares of degree completions can be likened to television shares, the technical term for the percent of the total audience watching a given program at a given time. In 2018, the most recent year of NCES data available as we write this article, a given program in the CIP system captured, on average, 0.09% of all completed bachelor’s degrees. The top quartile of degree programs producing the most completions—285 CIPS—have a share of 0.04% or greater. That is not a typo: most of the most popular degree programs have an extremely small share of the overall pie. A very small number do very well, comparatively speaking. CIP code 23.0101, English Language and Literature, General, claimed 1.6% of all degree completions in 2018. CIP code 16.0905, Spanish Language and Literature, claimed 0.3%. And CIP code 52.0201, Business Administration and Management, General, ruled the roost with a 7% share. Those and the other select outliers are the lone dots on the right-hand side of figure 3.

The outliers are not the story, although they do get a lot of press. The story is the cluster of very small numbers on the left side of the chart, which confirms that mean share is going nowhere but down, as represented by figure 4, which also reveals the consequences of CIP revision for individual degree share. A significant drop in the average followed the introduction of new CIP codes in 2010, and we can expect another drop in 2020. More degrees on offer necessarily means that each can expect a smaller share on average. Meanwhile, the median share number remains basically flat, at around 0.01%.

Fig. 4. Source: Chart by the authors created using completion data and institutional characteristics compiled in the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (provisional release data for 2018), nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/DataFiles.aspx.

As average share drops, one should imagine undergraduate-degree seekers spreading out, taking advantage of new and different degree options as they appear. The resulting dynamic is not a zero-sum game in which an increasing number of business majors means a decreasing number of history majors, for example. Rather, a select number of degree programs with historically large numbers of graduates are losing share to upstart degrees. Many of those upstart degrees were designed and are taught by faculty members who once, or perhaps still, teach in the majors that are now losing share. Some new degrees, moreover, surely are administered by the very same departments in charge of other, older degrees that have lost share.

Degree and department are not the same thing. English departments offering literature degrees might also participate in interdisciplinary majors with other departments, as well as offer several majors of their own in rhetoric or creative writing. Humanities professors trained in disciplines other than English regularly teach both in English and in degree programs across campus. This is not a sign that the humanities are in danger. To the contrary, it indicates that they are nimble, responsive, and sustainable. A student majoring in medical humanities rather than English is still pursuing humanistic study.

A different measure of audience better reveals the reorganization of university curricula than does degree share. In broadcasting, reach is the term used to designate the percentage of a total target audience exposed to programming at least once during a given period. In translating this concept to higher education, one might define reach as the percentage of students who could have chosen to finish a given program because it was available at their institutions. Reach enables new questions: instead of asking how many students completed a given degree program, reach asks how many students could access it. Discovering the reach of a degree program further encourages us to recognize the increasingly common approach of attracting comparatively small, but often profoundly committed, audiences to degree programs that exist in relatively few places.

Reach thus also offers a different way to contextualize and evaluate program success, one that may allow us to think a little differently about curricular innovation. It requires us to acknowledge, in a way share does not, that no program is available at every baccalaureate-granting institution. A bigger reach is not necessarily better: to the contrary, programs might seek to attract students by cultivating relatively scarce niches. That strategy may explain why median reach is so low—1.48% in 2018. After 2010 the majority of degree programs reached fewer than 1.5% of those who completed degrees. The average is raised significantly by a handful of ubiquitous degrees (table 4) and by programs that are expanding their reach (fig. 5).4

Fig. 5. Source: Chart by the authors created using completion data and institutional characteristics compiled in the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (provisional release data for 2018), nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/DataFiles.aspx.

Very few programs are nearly ubiquitous. For those outliers, high reach guarantees high share, but there is variance in this group, as seen in table 4. There are eight CIP codes that have greater than 80% reach, and their share varies from 0.7% (Chemistry) to 7% (Business Administration and Management).

| wdt_ID | CIP Code | CIP Title | Reach | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23.0101 | English Language and Literature, General | 85.74% | 1.60% |

| 2 | 26.0101 | Biology/Biological Sciences, General | 87.83% | 3.74% |

| 3 | 27.0101 | Mathematics, General | 83.93% | .90% |

| 4 | 40.0501 | Chemistry, General | 83.14% | .71% |

| 5 | 42.0101 | Psychology, General | 86.89% | 5.24% |

| 6 | 45.1001 | Political Science and Government, General | 83.15% | 1.69% |

| 7 | 52.0201 | Business Administration and Management, General | 80.74% | 6.98% |

| 8 | 54.0101 | History, General | 87.42% | 1.14% |

Table 4. The Eight CIP Codes with More than 80% Reach, 2017–18. Source: Table by the authors created using completion data and institutional characteristics compiled in the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (provisional release data), nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/DataFiles.aspx.

Reach indicates the full breadth and variety of institutional and student interest better than share does. Students find subjects to study for all sorts of reasons, and institutions create degree programs for all sorts of reasons, too. The mere fact that a degree program is available does not lead to large numbers of students in that program, although there are degrees with both high reach and high share, like psychology and business. Clearly, however, programs with both high reach and high share are not the only ones deemed sustainable in the current environment. Programs with dedicated followings can be low in reach. Low-reach programs will be necessarily low in share compared to the ubiquitous majors, but low-reach programs that find an audience might see their share increasing relative to other low-reach programs.

At a time when the broader landscape of higher education is changing, it would be perilous to rely on a singular metric of success. As every institution that has chased an emergent degree program knows, it can be costly to do what everyone else is doing, and to do so well enough to recruit students. It is far better, we think, to map the wider landscape and attempt to find a distinctive place within it. Humanities professors would also do well to adopt that broader view. If you mainly derive your academic identity from your department, it is likely that you are not thinking about the university or college where you work in a manner that will allow you to help shape its future.

Viewed together, reach and share suggest that when it comes to curricular development, it is easier to cultivate a new niche than to defend an old territory. Consider what is happening in the languages. Over the past decade the three major European languages of study—Spanish, French, and German—are decreasing in reach, while programs in other languages have seen their reach grow. Figure 6 shows this pattern for the twenty largest degree programs in foreign languages. For many of the other thirty-four CIP codes in family 16—for example, Sanskrit, American Indian/Native American Languages, Norwegian, and Turkish—increase in reach has been significant, although these programs’ share of total degrees remains negligible.

The languages follow the general pattern: as program variety grows, the overall tendency is toward increasingly uneven distributions. Colleges and universities distinguish themselves through differences in program offerings. To the extent that our programs help such attempts at distinction, we may understand ourselves as finding success in a different way than that available to us when we dwell on degree share alone.

Bigger may not be better if it does not allow your institution to distinguish itself in the context of decreasing numbers of traditional-age undergraduates and the resulting increase in competition to recruit and retain students. Lots of degree programs have very dedicated student and alumni populations, even if some of those programs are only graduating a handful of students every year. In an environment where niches proliferate, curricular programming is more like Netflix than basic cable, although thanks to the CIP scheme and the NCES reports, it is easier to see who is enrolling in what degree programs than it is to see who is watching what on video-streaming platforms. There is virtue in serving such diverse tastes and cultivating institutional distinction. The axiom that not all institutions can be all things to all people is abundantly clear to senior staff members, but it is best expressed through the creative activity of curricular development.

Thinking of reach instead of share may help us see how curricular innovation contributes to an increasingly diverse higher education ecosystem. Instead of imagining the goal as snatching students from another major, consider opportunities to team up with colleagues in other programs and departments in order to offer those students something new.

Finding ways to collaborate with other departments is an essential way to develop innovative degree programs. Many of the proliferating niche majors carve up existing institutional bureaucracies in creative ways, sourcing instructors from multiple units or identifying cohorts of faculty members within existing departments. Collaboration across departments to generate new programs is not in itself new, of course. Women’s studies, for example, has long enabled the joint efforts of humanists and social scientists, many of whom on small or less-well-resourced campuses have cross appointments. Today, such multidisciplinary experimentation is an emergent norm, as the wealth of new interdisciplinary degree programs in the 2020 CIP scheme revision confirms.

New amalgams like Economics and Foreign Language/Literature or Medical Humanities offer us intriguing possibilities to work with colleagues across campus rather than defend ourselves against them. In addition to responding to student demand and exciting changes in our fields, innovative emergent degree programs can breathe new life into existing ones, especially if they involve collaboration across departments. Faculty members who teach in both new and well-established degree programs may find that each program feeds the other in surprising ways.

In the decade ahead, large departments like English will likely continue to lose share. We should bear in mind that this decline not only indexes student demand but also indicates the ever-increasing diversity of fields with which all others clamor for attention. It is also true that the time of English as a big tent characterized by its ability to shelter other fields has passed. As degree programs proliferate across universities, these programs clearly want the distinction that comes from visibility within the CIP scheme. Embracing a future of program niches means an opportunity for English faculty members to make new alliances, and on more even terms. It is better to make allies than to claim turf, we can only conclude.

Notes

1 IPEDS reports on all sorts of numbers beyond degree completions, including financial data, faculty demographics, and staffing levels across student services and other types of administrative offices.

2 With the CIP Wizard tool (nces.ed.gov/ipeds/cipcode/wizard/default.aspx?y=56), users may look up particular CIP codes as well as compare various revisions to the taxonomic scheme.

3 There is surely a longer tale to tell here, one that would also include the drift of some versions of rhetoric from mass communications to English.

4 Space does not permit elaboration of data, but it is possible to identify the programs that are gaining traction in terms of reach, just as one can track gains and losses of share.

Works Cited

“Context for the Humanities Indicators.” American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2018, www.amacad.org/context-humanities-indicators.

“Introduction to the Classification of Instructional Programs: 2020 Edition (CIP-2020).”National Center for Education Statistics, 2019, nces.ed.gov/ipeds/cipcode/Files/2020_CIP_Introduction.pdf.

Schmidt, Benjamin. “The Humanities Are in Crisis.” The Atlantic, 23 Aug. 2018, www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/08/the-humanities-face-a-crisisof-confidence/567565/.

SED: Survey of Earned Doctorates: July 1, 2018 to June 30, 2019. National Science Foundation, 2019, www.nsf.gov/statistics/srvydoctorates/surveys/srvydoctorates-2019.pdf.

“Table 318.50. Degrees Conferred by Postsecondary Institutions, by Control of Institution, Level of Degree, and Field of Study: 2016–17.” National Center for Education Statistics, 2018, nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d18/tables/dt18_318.50.asp?current=yes.

“Technical Notes.” National Science Foundation, 2017, ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf19301/technical-notes.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.John Marx is chair of the English department and faculty adviser to the provost at the University of California, Davis. Mark Garrett Cooper is chair of the faculty senate and professor of film and media studies at the University of South Carolina, Columbia. They are each the author of three books, the most recent of which is their coauthored work, Media U: How the Need to Win Audiences Has Shaped Higher Education (Columbia UP, 2018).