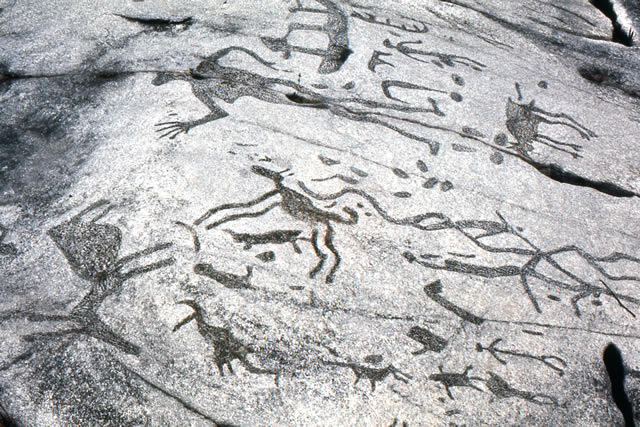

The central image is a humanlike being whose head appears to be taken up as a single eye. The figure itself seems to be a commentary on the fact of looking or the power of images: is it saying that the figure has been taken over by images or that the figure represents a visionary capable of feats of representational power? Are the nearby images making some form of obeisance to the larger central figure, or is their position in relation to it accidental? Indeed, in this whole set of images, are we to read each image on its own, or are there threads to follow or constellations to grasp? Or may all these approaches be deployed simultaneously?

Although these images have been treated as art pieces by at least one scholar (see Vastokas and Vastokas), here I will treat them as a mode of writing. In proposing that these enunciations be seen as writing, even literature, I am recalling the early Derrida’s expansive notion of writing in Of Grammatology (107–09) while also invoking a notion of the alterity of the other. However, and as will shortly become clear, the specific form of alterity involved here is grounded materially—through the concept of mode of production—in a way that does not allow it to easily fold into the generalized discussions of identity politics that circulate widely. So before proceeding I need to backtrack.

Indigenous people, like Anishnabwe, of the mid and far north of “Canada” base their way of life off a gathering and hunting mode of production, or what Glen Coulthard has called a bush mode of production (171). Across the boundary of mode of production all certainties dissolve: time, space, and subjectivity become organized around different principles and values. Fredric Jameson early in his theoretical work positioned the concept of mode of production as the third and widest horizon of interpretation (88–102). While literary theory invokes mode of production to set a literary text in a historical context involving some seismic shift in capitalism, or more occasionally in the transition to capitalism, in anthropology mode of production remains a marker of the sharpest or most distinct social difference. There is no other that is more other than those who remain attached to the distinct way of life associated with a different mode of production. The bush mode of production (or gathering and hunting) is even more different from contemporary capitalism than the agricultural, tithe, or neolithic modes of production, including such modes that were also colonized (see Wolfe, whose broad understanding of the concept and whose studies of the peasant forms remain invaluable).

The bush mode of production involves values, ways of seeing, ways of being, laws, gender relations, decision-making processes, and forms of writing that are markedly different from those we take for granted. Hence, if this paper has a modest program, it would be to recognize what we do not know. We do not know how to “read” the Teaching Rocks, because although we may recognize them—or choose to categorize them—as a form of writing, we are illiterate in that form. The “we” here would include non-Anishnabwe who do not know the protocols of interpretation associated with these inscriptions on rock. Consider figure 2.

Multiple utterances, inscriptions, folded over each other, some faded and in palimpsest-like relation, others sharp and distinct. Human and animal; possible clan symbols; spirit journey vessels; and in their midst, carved around a crack in the rock, a curvaceous, female-gendered image. It is said that the sound of water once emanated from the fault, that the image may be a guardian or at least positioned at the entrance of another world. She is constructed around a feature (the crack) of the rock itself. The image also recalls the notion of earth as mother that has some currency among many bush people. Here certainly we have a representation where the substance of the representation (image of a woman), the material of the representation (along a crack in a rock), and the subject of the representation (the earth as mother / mother as earth) collapse into each other: the earth as woman is woman as earth.

To show that such complexity is not unique to that image, I will refer to another. In figure 3 the turtle invokes “turtle island,” an image or notion or legend that Haudenosaunee and Anishnabwe alike use to describe and understand the world: the earth is an island carried on the back of a turtle. And in this image, again, we have the substance (image of a turtle), the material (rock, or the earth itself), and the subject of the representation (turtle island) all indistinguishable from one another:

I offer this partial, inadequate reading of these images to make three interrelated points: that most of us, settler colonials, do not know how to read these writings; that nevertheless “we” can know enough to know that there is a strong representational power to these writings; and that the use of the terms simple or complex (including my own above) is generally irrelevant to interpretive gestures except as part of the apparatus of colonization (in which everything to do with the bush mode of production is “simple”). To actually make a strong interpretation of these writings we would need to talk to someone: a spiritually knowledgeable Anishnabwe teacher. But, finally, my real purpose here is to raise the issue of what has happened to the Teaching Rocks, what is happening all around us to similar places, and what therefore is happening to the people associated with these places.

For many years (as I have been told by my friends from Curve Lake First Nation), the Teaching Rocks were buried under moss. Elders would bring initiates and offer tobacco, tell stories, and show specific images, deploying them in healing ways. Then in 1924 a local, nonnative person “discovered” the Teaching Rocks. All the moss was removed, and in classic colonial nominalist practice the site became known as the Peterborough Petroglyphs and also became a favored picnic hike for local people, both nonnative and Anishnabwe. The sound of water gurgling underneath acted as accompaniment to those who visited. But, exposed to the elements and especially to acid rain, the images began to erode. Good-natured, helpful, non-Anishnabwe grew concerned about the immanent disappearance of this powerful sacred site. Meetings were held. Funds were raised. A solution emerged. A protective structure was built around one core area of the Teaching Rocks, in which all the above images are found. Now “protected,” the teaching rocks can be visited at Petroglyph Provincial Park (established in 1976), encased in the structure pictured in figure 4.

The sound of water faded and disappeared as this structure was built. There are other images around the building that are not so protected. As well as the physical structure, explanatory signs “contain” the logic of the Teaching Rocks, telling viewers that, for example, there are some number of similar images found around the Great Lakes: categorization as interpretation. In the period of political decolonization that emerged at around the same time (the 1970s) and especially under the impetus of a push to aboriginal self-government in the 1980s, the site has come to be managed by nearby Curve Lake First Nation, though it remains a provincial park. Traditional teachers and users of the site have keys and can visit and practice their spiritual activities away from the objectifying gaze of visitors or tourists. But protection itself, conservation in a museum or conservation on site, can also act as one of the most powerful destructive mechanisms of totalizing power. Safe, contained, renamed, surrounded, preserved, embalmed, sterilized: an evocative challenge to our mode of writing opening onto a substantial questioning of our mode of being is here repositioned as a cultural curiosity, the object of a settler colonial, imperial gaze.

Consider and compare another set of teaching rocks (fig. 5), images located in roughly the northwest corner of Anishnabwe territory, also known as the Manitoba Petroforms, in Whiteshell Provincial Park in my home province. Here, the images are produced not by carving into the rock but by piling stones on top of the large flat surfaces of boreal, igneous rock that serve as canvas or writing paper. It is as if these sets of images exist in some relation or tension with each other, a mirroring or reflection.

Here too we find one of several turtles, where again the tripartite elements of representation become inseparable. Scattered across an area of several acres, the distinct images pose the same problems as their eastern relatives: do we read each image as a singularity? Do we tell stories that connect multiple images or all of them? Does a single image sit in several constellations? Among snake, spirit vessel, clan figures, we find, again, the mother that is earth. Partly covered in growth, made of about twenty rocks, she lies flat, simultaneously sinking into and emerging from the earth: she is called Bannock Point Woman. She has arms, legs, head, breasts, and a rounded belly. Is this mother the earth? Is this earth the mother? Is every earth also mother? Is every mother also earth? No doubt many present and past visitors do not know of the spirit “double” that exists far to the east, and, taken together, these earth mothers gently but insistently question prevailing notions of the value of uniqueness and of the establishment of genealogical relations.

This site is in a large provincial park. It is marked by sparse signage and accessed through a trail from a parking lot off a little-used paved road. There is no structure, not even a fence, surrounding the site, though a bit of signage at the parking lot reminds visitors to respect the images, which are vulnerable to the boots of visitors. That the images remain intact is a modest testament to the respectful behavior of the province’s citizens. The province’s leadership, however, does not evidence such a positive ethical example. Among the most powerful sacred sites in northern Manitoba (Inninuwak/Cree territory), two, the Footprints (figs. 6 and 7) and Wasagejak’s Chair (fig. 8), were flooded in the profiteering interests of the export of hydroelectric power.

The story of the Footprints is a cautionary tale. The site originally had a number of footprint-shaped and

-arranged indentations going straight up a sheer wall of rock (the story associated with it tells of the trickster Wasagejak getting his head stuck in a moose skull and running to shake it off until he ran into the rock, which he then walked up). In the 1970s the site was flooded as part of a hydroelectric grand project called the Churchill River Diversion and Lake Winnipeg Regulation. Two of the Footprints were removed and set in a concrete slab, which sat at a variety of destinations until it was returned to rest on the bank of the river near its original site. Although there is evidence of traditional activity at the site, at least some local elders believe these are not the real Footprints but a copy, attesting in my view to the fact that they feel the site has lost its power.

The story of Wasagejak’s Chair is easier to tell. It was flooded as part of the same project. I have no pictures of the chair, but in figure 8 you can see a representation of the void it has left behind.

The Teaching Rocks, northeast and northwest, have been constructed by indigenous peoples, specifically by hunting people. The Footprints and Wasagejak’s Chair may have been found, constructed by people, or constructed by more-than-human, supernatural beings. Figure 8 shows rather starkly what we have left to learn from these powerful sites and moves me toward a theoretical point.

I deploy the term totalization to describe the social and cultural processes that assiduously refashion the bush mode of production. The term signifies the transformation of bush ways of embodying space, time, subjectivity, landscape, relations, ways of seeing, and modes of being into forms that are conducive to the accumulation of capital and to the expansion of the commodity form. While these two forces were well known to Karl Marx, he did not specifically theorize the state as another instrument of totalization, as a structure that sets into place the preconditions that will allow for, indeed call for, capital accumulation. A state can also, of course, be totalitarian: that is, and here I can recall Hannah Arendt, a state form that relies extensively on a police-surveillance apparatus to ensure the production of politically docile bodies (447, 457). Totalization and totalitarianism are distinct processes. When they conjoin, as they sometimes do, they make for a particular and historically specific, dangerous hegemonic form. To some extent, the regime of George W. Bush moved the United States in such a direction. Contemporary settler colonies almost always rely on some combination of both forms. In Canada, what could be more totalitarian than residential schools? In Canada, what could be more totalizing than the day schools that both predated and came after residential schools? The state-produced and monitored form of relating to time (say, clock time) has been socially naturalized and becomes a presupposition that everyone is expected to conform to: totalization. The systems of coercion used to ensure that indigenous people do not miss their appointments: totalitarianism.

Both the brutality of planned and orchestrated destruction of sacred sites, that is, totalitarianism, and the “accidental” generational “forgetting” of sacred places, that is, totalization, are busily doing their work erasing, containing, and sterilizing as many of these sites from the settler colonial landscape as they can and as quickly as possible. That many such sites remain in the mid and far north of Canada is only a signifier that work remains undone. Consider the sites in figure 9 from the western arctic, Northwest Territories, or Denendeh.

This waterfall is far up the Redstone River, which flows into the Dehcho (Mackenzie River) from the Mackenzie Mountains. A female spirit is said to reside or be embodied at this site. It is an unmarked site and not frequently visited. The waters are thought to have healing power. The “blackness” that is seen in the rock to my untrained eye indicates a possible presence of oil or natural gas in the limestone that could be extracted through fracking. It is therefore entirely possible that this site will, at some future point, be disappeared by a bulldozer or drill rig. And consider figure 10.

This sacred site sits at the foot of Red Dog Mountain on the Begadeh (Keele River), which also flows from the Mackenzie Mountains to the Dehcho. It is the subject of a powerful ancient narrative, still told by mountain Dene (Begade Shuhtagotine). Hunters traveling up the river by jet boat leave bullets or tobacco or coins at this place as they pass it.

Figure 11 is a photograph taken on the Dehcho itself but quite far upstream, between the communities of Norman Wells and Fort Good Hope: outlined along the side of a cliff is Wolverine, a powerful being in Dene narrative and philosophy. The small pointed rock outcropping is the tail, and if one follows that down the cliff a brief distance, the head and legs of Wolverine become clear. The site is known as the place where Wolverine turned to stone, in reference to an event embedded in the lengthy story cycle involving that character. As with the waterfall, as with Red Dog Mountain, there are no markers. In my many travels by boat from Norman Wells to Fort Good Hope, I passed the place where the Wolverine turned to stone without knowing of it. The fact that these sites are unmarked both protects and endangers them: they are intentionally visited by relatively few people, mostly local Dene or Métis, and therefore not disturbed. A proposed Mackenzie gas pipeline would lead to a huge construction project near this site from which it could be damaged or destroyed.

When the memory of these sites is lost, the sites are lost: they are irreparably tied to their place in memory. While some of these may be mapped by, for example, the very good ethnographers working with the Northwest Territories Heritage Museum, it is possible that my own work may be the only documentation of their existence (needless to say, this dramatizes their deeply precarious status). And of course this small sample only gestures toward the many other similar sites embedded in the landscape. Negotiating an ethical relationship to these sites must be premised on face-to-face interaction with the people who know the stories. Advertising the sites through park structures can lead to protection but also sterilization. Keeping knowledge of the sites restricted can lead to accidental destruction. The solution offered by the Footprints is not an acceptable middle ground. Each site must be placed under the stewardship of the indigenous people who read it, who themselves must decide how to balance official protection, desecration, commercial value, continued spiritual uses, and so on.

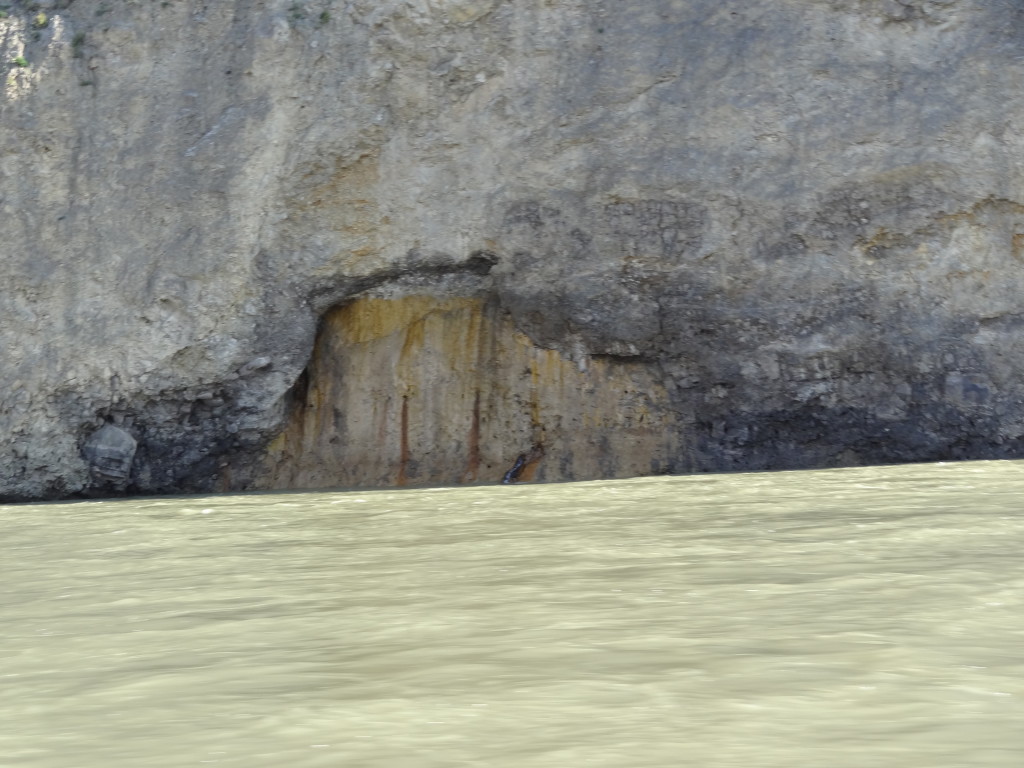

Another example, from Nunavut, land of the Inuit, in the eastern portion of the arctic, raises similar and additional issues, including the broad question of how we see as epistemology (or how we “train . . . the imagination for epistemological performance,” in Spivak’s phrasing [122]). Halfway up the “cut,” or ledge, that traverses this cliff face a cave can be seen, itself briefly obscuring the cut. The path leading up to the cave is known as the Blind Man’s Walk (fig. 12), owing to a lengthy and powerful story cycle involving a central character who, after much travail that in part left him blind, walks across the ice, up along the ledge, and through the cave, at which point he regains his sight.

Elsewhere I have commented on the desire that “we” might traverse this passage and come to see the world with newly reenchanted eyes (I note the influence of Michael Taussig’s work on this idea). A few blasts or drills to merely explore for the minerals that might be behind this rock face will be enough to erase this marker forever. The dominant social order is more likely to engage this place in the search for abstract wealth than to walk through it in an attempt to stretch the boundaries that circumvent the forms of meaning that circulate to entrench the established order. That is, do we see the possibility for capital accumulation to take place here (in which case we remain blinded by the promise of a certain restricted form of wealth as capital), or do we see the possibility of another form of wealth associated with another form of seeing?

To be clear, placing signs to mark the fact that these are signs is not what ethics demands, is not an adequate ethical response. Developing an ethical relation with indigenous communities in which asking and listening are the primary and foundational actions would allow for the stories that unfold the significance of these sites to be told. The continuing capitalist colonial conquest of the Americas carries and rests on a set of presuppositions that foreclose such asking and listening. The bottom line is to say that more lands should be under the control of more bush peoples, but this view challenges the logic of primitive accumulation that underwrites the global economic forces pressing on these peoples, these sites, this knowing, these practices, this reading, these ways of seeing.

Because the capitalist colonial conquest of the Americas is not some long-past set of events but rather a continuing and urgent politics, this analysis can finally move to its conclusion. A final few images will anchor this element.

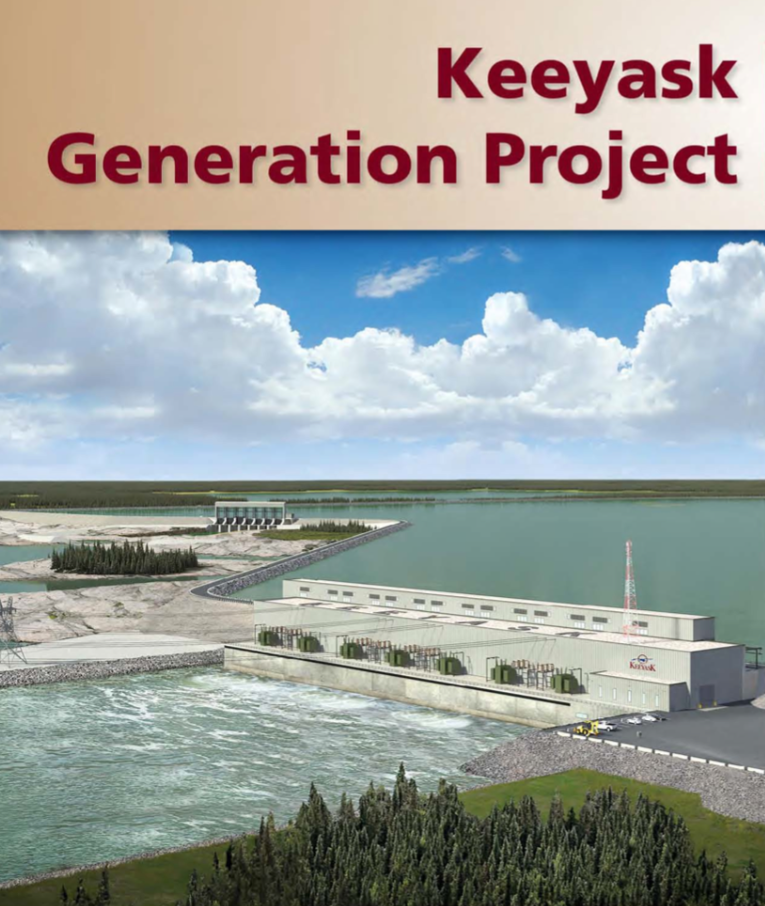

The Keeyask (Gull) Rapids on the Kitchi Sipi (literally the “great” or “grand river” but on the maps the “Nelson River”) in northern Manitoba (fig. 13) are the last natural spawning grounds of an endangered form of sturgeon. Along the river’s banks at this site, but not found by the archaeologists who searched for it, is an ancient, sacred offering stone. Figure 14 is an image of what the future holds for this place, the Keeyask Dam, a project designed by a crown utility, Manitoba Hydro, largely to produce electrical power for export to the United States.

Although the project involved a “partnership” agreement with elected leaders of four of the nearby First Nations, the agreement is flawed in many respects and will likely produce few benefits (a similar agreement for a nearby dam and First Nations community has led to an enormous debt load there, not likely to be alleviated for decades). Along with other nongovernmental organizations, a group of locally and university-based activists, to which I belong, engaged in a struggle through public hearings to prevent this project (fig. 15).

Under the name the Concerned Fox Lake Grassroots Citizens, this group made a strong effort to articulate the view of traditional harvesters and land-based Inniniwak (bush Cree) that the project was destructive and unnecessary. We spoke, but we were not heard. The Manitoba Clean Environment Commission recommended construction of the project, the province agreed, and the construction is, as this is being written, under way.

The image of Keeyask Rapids in figure 16 would reasonably be understood or seen as a representation of what we used to call “nature.” It is not an image of nature. It is an image of history. Perhaps history in Jameson’s sweeping sense:

History is what hurts, it is what refuses desire and sets inexorable limits to individual as well as collective praxis, which its “ruses” turn into grisly and ironic reversals of their overt intention. But this History can be apprehended only through its effects, and never directly as some reified force. This is indeed the ultimate sense in which History as ground and untranscendable horizon needs no particular theoretical justification: we may be sure that its alienating necessities will not forget us, however much we might prefer to ignore them. (102)

We refuse to be done with the issues created by restructuring the hydrology of northern Manitoba that will suit the exigencies of a regime based on capital accumulation. Too much is at stake. In the early summer of 2015 as I toured artists around hydroaffected communities, I met with the Inniniwak elder who had drawn me into this struggle, Noah Massan, and documented the devastation to his trapline, which I had visited in an untouched state the year before. Together, in tears, we vowed to fight on. Later that month we met with sixty people, academics and activists, nonaboriginal and indigenous, and planned the next phase of our struggle. The work of mourning must necessarily be brief: the work of alliance building, of dissidence and opposition, struggle and resistance, remains too urgent to allow for rest. Negotiating these sites involves the struggle to remember that there may be things in this world of a different kind of value that cannot be discussed in the terms proposed by the logic of capital accumulation and its brutal henchman colonialism. These sites, and the interpretive powers of the people who read them, open a world where the mode of valorization itself acts as a check on the avarice-laden assumptions of the dominant logic. May the bush sites and the bush stories discussed here open a window onto that world.

Works Cited

Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. 1951. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1973.

Coulthard, Glen. Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. U of Minnesota P, 2014.

Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. 1967. Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Johns Hopkins UP, 1976.

Jameson, Fredric. The Political Unconscious. Cornell UP, 1981.

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization. Harvard UP, 2012.

Taussig, Michael. Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man. U of Chicago P, 1991.

Vastokas, Joan M., and Romas K. Vastokas. The Sacred Art of the Algonkians: A Study of the Peterborough Petroglyphs. Mansard Press, 1973.

Wolfe, Eric. Europe and the People without History. U of California P, 1982.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.Posted July 2016