As the numbers of students in humanities departments and liberal arts colleges drop dangerously low, we need to reframe the question of how to increase humanities enrollments to pose a far more important one: What do our students lose by not taking humanities courses?1 We argue that they lose too much. If we believe the mission statements of most humanities departments, what students lose when they do not take humanities courses includes critical reading and creative thinking skills, clear writing, historical and contextual understanding, and all the necessary skills employers say are key to advancement and that we assume to be crucial for democratic participation in a just society. If we believe all that, then we in the humanities must also take on the deep responsibility of ensuring that our courses do what we say they do. We must prepare our students to be empowered to think and to act critically in the contingent, precarious, overwhelming world we have bequeathed to them.

Now is the time for those of us teaching in the humanities to do more than take a defensive posture in what amounts to a global assault on the humanities. We are not interested in fueling polarizing arguments about the importance of humanities versus STEM. On the contrary: in this essay we argue that humanistic thinking and humanistic skills are indispensable for preparing our students for a technology-dependent world—and, in 2019, there is no other world than a technology-dependent one. The humanities are more crucial than ever in this world, which is dominated by simplistic and even dangerous technological imperialism, and the belief that problems caused by technology will be solved by technology. How do we in the human and social sciences take up this responsibility? How do we train activist, global citizens who feel empowered to demand and create better technologies for a more equitable future? Are the humanities up to the challenge of leading the way?

STEM alone cannot save us. Nor can STEM training alone help our students succeed. Anyone who still believes that simply learning how to code will train students for more than menial, contingent, and underpaid employment hasn’t been paying attention—or prefers not to look (see Gray and Suri; Semuels). Anyone who believes entry-level employees are promoted to executive positions—even in tech companies like Google—primarily on the basis of STEM skills hasn’t read the vast number of workplace studies that emphasize the role of so-called soft skills in advancement.2 We are all aware of the disaster of contingent, exploitive labor in academe; we need to be equally sensitive to the adjunctification of the many other professions that our students (undergraduate and graduate) will be attempting to enter. Our students can no longer count on stable, rewarding careers. Even obtaining an entry-level full-time job requires evidence of skills beyond a college diploma. In any number of surveys, employers insist they want beginning employees who possess the full array of written and verbal communication, project management, and collaboration skills across different skill levels, cultural backgrounds, and languages. That, again, is the territory of the humanities—or we say it is in our mission statements.

What we want to underscore is the relevance of active learning to our particular historical moment.

Numerous studies, including surveys of educators and experts in executive training and professional development, insist that college graduates lack the essential skills we as humanists have the unique opportunity to teach: people skills, communication skills, critical and interpretive skills, collaboration and project management skills.3 Other essential skills the humanities teach include working effectively in groups to solve problems together; reading and interpreting complicated data, events, and texts; undertaking original research; and understanding and making sense of ambiguity (the gray areas). Engaging in the humanities, too, fosters self-awareness, ethics, decision-making skills, good judgment, clarification of values, and the ability to know when and how to appropriately apply newly acquired skills beyond the classroom.

In this essay, we argue that if our humanities courses cannot deliver in these areas, something is seriously wrong. Humanists who care about the fate of our students—and, in fact, the fate of the world—should be taking our mission seriously and delivering on our promises. We need to ask ourselves (not in a general way, but as individuals in this profession) if we are really doing what we say we do in our humanities classrooms.

Below, we offer several relatively simple techniques and exercises that make it easy to create and sustain a student-centered classroom. We are hardly the first people to advocate progressive, engaged education.4 What we want to underscore is the relevance of active learning to our particular historical moment. We argue that preparation begins in the humanities classroom—all of our classrooms: small and large, at elite private institutions or large public ones, in discussion and lecture classes, and in any setting, including developmental classes at community colleges, general education courses, introductory literature courses, composition and creative writing courses, and graduate-level courses, even the most specialized doctoral courses when students are on the way to writing a dissertation.

Essential skills may be foundational humanities skills, but rarely do we consider them foundational in our reward systems. That is, we are not typically encouraged to value these skills or to teach them deliberately. Essential skills are also, paradoxically, both easy to teach and, at the same time, not transparent. Most of us who were trained mainly by emulating our own professors find it difficult (at first) to reshape our lectures and discussion methods to include students in the building and leading of our classrooms—active learning situations that offer students an opportunity to master essential skills. It is often equally difficult for students to realize when and how they are mastering these skills. Rarely do we describe for students what and why they are learning. Yet reflection or metacognition (the structured, intentional consideration of what one has mastered and how one has mastered it) is one of the most important cognitive tools we can pass on to our students.

For the traditional humanities course to truly help students master essential skills, students need to be included in the learning process. In other words, simply mastering what someone else tells them to master is the opposite of gaining critical, creative, constructive abilities students can apply beyond the final exam, the course, and the diploma. To truly help students master essential skills, we need to lift the curtain and show them the string. Who decided this material was important to learn and why and how did they select this curriculum instead of many possible other ones? What criteria did they establish and use to make such decisions (and, in any situation, how does one establish and then implement such decisions)? What skills will this lesson build on and what skills will it build toward? Where will these skills be applicable in students’ everyday lives? Why are we covering this material at this particular moment in history/herstory? These are deep and powerful questions that change how students participate in the course and what they take away from it into the rest of their lives.

We cannot just do lip service to the rich, deep, critical, and creative thinking provided by the humanities, as described in our mission statements and our op-eds. We need to deliver the goods. We need to rethink our curricula, of course.5 That is crucial. At present, almost all departments (including those outside the humanities) are based implicitly on a model of self-replication: we teach so that our students will become college professors like us. That’s a false goal. It always has been, but it is now more irrelevant than ever. We need to do the very hard work in the humanities of taking the lead at our institutions to redesign our programs in ways that are relevant, urgent, meaningful, and indispensable to students’ lives, including work lives that do not resemble those of their instructors.

To truly help students master essential skills, we need to lift the curtain and show them the string.

This is an arduous process; it requires thoughtfulness and generosity and a willingness to be equal parts tough-minded and willing to give up one’s own turf for the greater good of preparing students who have little chance of replicating the profession of the professor. But even as we work toward the larger goal, we can begin to change the humanities through the way we teach and the way we talk about learning. We can do this, as individual instructors, in our own courses, literally tomorrow.

At even the most restrictive college or university, even those where learning has been reduced to outcomes and deliverables and requirements, any professor can begin to transform the humanities classroom into a site where students not only learn the content but also understand why the skills, tools, and methods of a course will be important to them beyond the grade and the final and how they can exercise these new muscles in other subjects and in the world beyond school.

The ideas we offer are not just for tenured, secure, full professors. Nor are they only for those with a lot of time to experiment. Investing the time in rethinking how one teaches does not require giving up one’s own research agenda. That, too, is a binary we find senseless and antithetical to the revised forms of thinking required to transform the humanities from something dismissed (wrongly) as peripheral to the absolutely essential.

Here are six ways to transform the humanities classroom to help students develop the essential skills that they need to meet the challenges of the world they have inherited.

I. Share the Floor

How It Works

Instead of lecturing first and polling the room for questions later, begin by sharing the floor: give students time to share their ideas about the topic for the day. Opt for a low-stakes-but-intensive activity such as the classic Think-Pair-Share (TPS) in which you ask a question and each student has time to write down a quick, individual response. Ninety seconds is plenty. Students then work with a partner and take turns sharing their responses and discussing them (another ninety seconds). Finally, they share what they discussed with the entire class either verbally—if you ask for volunteers to share—or by posting to the class wiki or blog or by handing in their writing (we use index cards; see fig. 1) for you to read and reflect on. You might even summarize salient points for the class later.6

Why It Works

Rather than selective methods (where only two or three students raise hands in answer to questions), which tend to single out students who are most likely to replicate their professors, inventory methods are structured for what the American Psychological Association calls total participation (see fig. 2). Every student contributes something, and every student speaks and is heard by at least one other student and by the instructor. Inventory methods like TPS highlight the value of essential skills such as actively engaging and participating, taking a moment to collect one’s thoughts and then share them, and learning how to hear all available ideas in a group (not just those of the two or three people who tend to dominate classrooms—and business meetings, too). Inventory methods help students feel there is purpose in their education, not just in the education of the voluble few. These methods also show students that they are not passive receivers of information; they are thinkers and keepers of ideas, insights, and knowledge. Total participation helps students gain the confidence they need to apply knowledge, to develop independent problem-solving and research skills, and, when working in pairs or small groups, develop essential collaborative skills as well—especially (and this is key) if you, the instructor, reflect on this process as it unfolds and underscore what and how students are learning. (We have each followed a TPS strategy, for example, with a reflection in which we ask students where such a method might prove useful, and students have offered examples of everything from the workplace to the community center to the family dinner table.)

Fig. 1. Typical index card question for one of our Think-Pair-Share activities at the beginning of the semester. We try to do one quick, low-stakes “inventory” exercise every class period.

Fig. 2. Undergraduate students in a CUNY Peer Leaders and Mentors Program respond to their own student-generated poll. “Undergraduate Leaders 2016.” Flickr, uploaded by Futures Initiative, 28 July 2016, flickr.com/photos/132429829@N05/28873856176/in/datetaken/.

II. Welcome Students into the Learning Process

How It Works

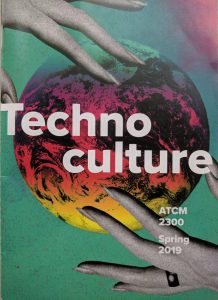

Make your syllabus into a warm welcome, not a rule book. Anne Balsamo, the inaugural dean of the new School of Arts, Technology, and Emerging Communication at the University of Texas, Dallas, does this in her two-hundred-student introductory Technoculture lecture course, an offering in the core curriculum of this STEM university. She makes her syllabus a readable, inviting booklet (see fig. 3) that not only outlines course content but also explains why and how skills such as researching, analyzing, and synthesizing are important both in and outside the class. Balsamo also, on facing pages of the syllabus booklet, includes the official university policies on, for example, academic honesty (a page detailing the “disciplinary action” the university prescribes) and protecting “your intellectual credibility.” The former explains what happens to a student who messes up. The latter honors students for their credibility and offers three “basic tips” for protecting one’s integrity: learning to love citations, giving credit where it is due, and reading Wikipedia critically.

Why It Works

By treating students not as kids or potential miscreants but as intelligent and honorable human beings, an inviting syllabus welcomes students into the methods and processes that we academics esteem. It also underscores why we value such things as intellectual integrity and citation and helps students develop the skills necessary to credit ideas they gain from other sources. It invites students to practice and apply methods and newly acquired skills while knowing that they are doing so. Treating a largely STEM student audience this way introduces the practices and values key to our discipline—and, we hope, to the world. In addition, students are encouraged to take pride in applying the principles well. These are essential skills and practices that will serve them in every area of life beyond the classroom.

Fig. 3. Front matter of the syllabus booklet for Balsamo’s Technoculture course.

III. Prioritize Student Goal Setting

How It Works

On the first day of class, create an activity that has students develop their own goals and learning outcomes for the course. You could start with a TPS activity, asking students to write down their goals for the year (see fig. 1, for example). You might also invite them into a shared Google Docs document where they can suggest changes to the learning outcomes on the syllabus. Or you could put students into groups of three or four and have each group come up with two or three aspirations for what they will accomplish together in this course. The responses can be shared on a whiteboard or some kind of collaborative tool (e.g., in Google Docs), and, with editing, these student goals can go onto an evolving syllabus as the learning outcomes for the course. Ideally, you and the students will refer back to these goals throughout the course to see how many are being achieved. (We are continually surprised and even inspired at the creativity and idealism of our students when we encourage them to aim high.)

Why It Works

Today’s college students have been subjected to a lifetime of outputs, outcomes, and seemingly mechanical (and meaningless) standardized goals. Many of us, as instructors, churn out learning outcomes as if they were meaningless, too. Something magical happens when we turn a seemingly quotidian task into an invitation for students to voice their dreams for their education. The students may need coaxing. They definitely need to know that you believe in them. But if they trust you and the situation, they will take the opportunity and they will shine. Students need to unlearn years of being taught that they aren’t experts or innovators. Activities like this one guide them in taking ownership over their own education and taking themselves seriously as colearners. Balancing ambitious goal setting with practical expectations takes practice in the essential skill of project management. This is a perfect opportunity to guide students in translating their loftiest aspirations to practical, attainable goals. Moreover, this class-wide activity teaches students the essential skills of valuing both individual and community goals and of linking personal achievements to community success.

IV. Follow Major Lessons with Reflection Activities

How It Works

In addition to lifting the curtain before an activity, set aside time for student participation after a lesson, either for an independent reflection, TPS, or an exit survey. At the end of a lecture, Jonathan Sterne, who lectures to as many as six hundred students at McGill University, often asks a question and gives students a few minutes to jot down a response. 7 He has students sign and hand in the cards, and so they also serve as an efficient way of taking roll. His teaching assistants use the cards from their sections to guide small-group activities, and he uses patterns he finds in the answers to shape future lectures. We both, too, use exit tickets in most of our classes, large and small.8 Our favorite question: What did we discuss today that you will still be thinking about tonight? If there’s nothing, then what should we have discussed?

Whether you use a formal or informal method for reflection, the point is to have students recall something important that resonated with them from the class, something they would like to take with them into the world beyond the classroom. And if they can’t think of anything, ask them to write down a burning question, one that will keep them up at night. This alternative question prompts students to develop independent research skills. One reflection activity per class is ideal. And it is especially meaningful on the final day of class.

Why It Works

Following an activity or lesson with a metareflection creates a space where some of the most important and long-lasting lessons are committed to memory (see fig. 4). Even if students forget the content or activity itself, they are likely to remember their reflections about what they learned and about how to apply that knowledge in other settings. There is perhaps no more essential a skill than taking specific content learned in one context and applying it in another. Isn’t that one of the great, compelling reasons for reading literature? In a novel or a play, we learn how someone else navigates a particular situation; that lesson has particular meaning if we can relate to the situation and think about how we might or might not respond in the same way. In poetry, we see how a particularly creative and dexterous mind recombines words and images in a way that is powerful and beautiful and meaningful. Reflecting on the importance of the literary—and the uniquely essential role of the writer in society, throughout time—is something that can slip through the cracks when racing through content. Storytelling is an essential skill in every aspect of life—workplace, family, democracy. If a humanities class cannot teach that essential skill, then why bother?

Fig. 4. Poster from the Undergraduate Leadership Institute introducing the concept of metareflection or thinking about the skills we master through reflecting on our own and fellow students’ thought processes. “Meta-Cognition.” Flickr, uploaded by Futures Initiative, 19 Aug. 2015, flickr.com/photos/132429829@N05/20586409980/in/datetaken/.

V. Give Students a Say in the Curriculum

How It Works

The simplest way to do this is to ask students to vote on one event, piece of art or music, problem, text, topic, or unit to spend time on. There are myriad ways to involve students in the creation of the course. For example, you could ask for one-paragraph proposals in advance, written individually or in small groups, and then set aside time for class-wide presentations and discussion, followed by a poll or vote by ballot. This works best if students have had some time to get more familiar with the course content. We don’t recommend doing it on the first day. Whichever way you decide to structure the vote, you will need to make time for discussion, time to build the process into your syllabus, and time to include comments about how the process itself is part of the learning. We find that small group discussions that lead to class-wide discussion work best. We also find that every aspect of a course is enlivened and enriched when students choose even one small unit together. (After you feel comfortable having students choose a small part of the curriculum, you might even try something truly radical, such as having students create a whole unit or the last half of the course—or even the entire course. That takes a good deal of preparation, or scaffolding, but it can be done responsibly and with stunning impact.)9

Why It Works

Now that we have lifted the curtain by explaining research methods and best practices, by explaining how and why activities and lessons work outside the classroom, and by letting students in on cocreating learning outcomes, having students take a hand in actually designing the course and the syllabus is the ultimate exercise. Cocreation teaches essential leadership and entrepreneurial skills through both critical and creative thinking. It helps students master the essential skill of coming up with a realistic solution to a problem (e.g., choosing only one text that everyone can read in a week from the dozen or so that are proposed and then finding a responsible rationale for why they have made that choice and not a different one). Making room for students to set the direction for their community and then to work together and agree by consensus allows them to practice all the essential skills they will need down the road for effective professional teamwork.

VI. Provide a Public Platform

How It Works

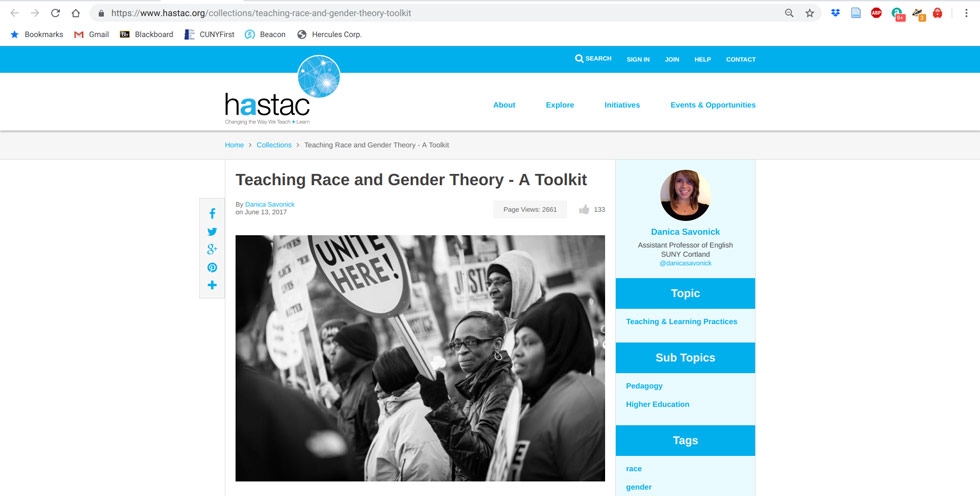

Whether writing to classmates on Blackboard or another tool like Slack or on an open platform (anything from WordPress to Twitter), students write differently when they write only for their professors than they do when writing for a wider audience, including an audience of peers. The research of Andrea Lunsford, professor emerita at Stanford, suggests that students are better writers in these peer contexts (see, e.g., Lunsford et al., “College Writing”; Lunsford et al., Everyone’s an Author; Ede and Lunsford). We especially advocate having students write for a community that is relevant to them. A good one is HASTAC, the Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory, the world’s first and oldest academic social network. Founded in 2001 (before Facebook or MySpace), HASTAC includes seventeen thousand network members dedicated to “changing the way we teach and learn” and has hosted 1,430 student HASTAC scholars over the years. Anyone who registers for the network—and it is free to do so—can post or comment. Any professor can create a class group on the Web site (e.g., see fig. 5), and students can post their own work either for other group members or open to the world, using their own name or a pseudonym.10

Fig. 5. Landing page on HASTAC for “Teaching Race and Gender Theory—A Toolkit.”

Why It Works

As soon as students write for an audience beyond the professor and the classroom and use some kind of technology to publish their work, they are mastering a range of essential skills. If they read the terms of service agreement carefully, they learn ethical and unethical uses of data—surely a survival skill today. They learn about security and privacy and also about publicity in a serious, academic, respectable context that can serve their future career and personal goals and can help them build a portfolio of public, online work that supersedes possibly traces of recreational online activity (such as an Instagram account). Public writing helps students understand how to write in a public voice, with an appreciation for audience and the essential skill of communicating what one knows to someone who, unlike one’s instructor, may not share their expertise. In addition, this assignment affords students a constructive opportunity to develop their professional public presence while learning how to protect their digital identities from unwanted surveillance.11 Understanding how to secure personal information online, and having the option to create and use a dummy account for additional protection, is critical to everyone’s future.

These are only a handful of techniques that honor the importance of the humanities in teaching essential skills (power skills, critical skills—not “frills”). The techniques help any instructor transform a humanities course (at any level, at any institution, including the most traditional) into an active learning environment, in ways both small and large. While we are undertaking the typically arduous, painstaking, and lengthy process of redesigning outdated departmental majors and minors, university-wide general education requirements, and interdisciplinary relations between the human and social sciences and the STEM departments on our campuses, we can walk into our humanities classrooms tomorrow and help our students understand and master skills that will change their lives. Will they learn art, classics, history, linguistics, literature, music, philosophy, and more? Will they learn how to read, to write, to perform? Of course they will. They will also learn why learning how to think and to do these things critically and creatively are constructive, essential components of their education and survival skills in a challenging world.

Notes

1. For the ADE report on the decline of undergraduates declaring English as a major, see Cartwright et al.

2. See the outcomes from Google’s Project Aristotle in re:Work (“Guides”) and outcomes from Google’s Project Oxygen in Impraise (“Project Oxygen”); for a narrativized perspective, see Duhigg; for outcomes from similar studies, see Woolley et al.; Rainie and Anderson.

3. For an overview of several recent studies that repeat this finding, see Wood.

4. Among the vast array of books and articles on progressive pedagogy, for further reading, see Davidson, New Education; hooks; Lang; Morris and Stommel; Shor.

5. See the PMLA forum on The New Education in the May 2018 issue (pp. 667–707), and Davidson, “New Education and the Old”; see also Warner.

6. For more on TPS, see Katopodis, “Dialogic Methods.”

7. See Dolan and Sterne on the importance of peer-to-peer conversation and the value of collaborative tools.

8. For more on exit tickets, see Katopodis, “Entry and Exit Tickets.”

9. For an example of more radical cocreation with students, see Katopodis, “Lesson Plan.”

10. For examples of course Web sites on HASTAC, see Davidson, “Black Listed”; Katopodis, “Mediating Race”; Savonick.

11. See Glass on protecting oneself from surveillance.

Works Cited

Cartwright, Kent, et al. A Changing Major: The Report of the 2016–17 ADE Ad Hoc Committee on the English Major. Association of Departments of English, July 2018, ade.mla.org/Resources/Reports-and-Other-Resources/A-Changing-Major-The-Report-of-the-2016-17-ADE-Ad-Hoc-Committee-on-the-English-Major.

Davidson, Cathy N. “Black Listed: African American Writers and the Cold War Politics of Integration, Surveillance, Censorship, and Publication.” HASTAC, 11 Sept. 2017, hastac.org/groups/black-listed-african-american-writers-and-cold-war-politics-integration-surveillance-1.

———. The New Education: How to Revolutionize the University to Prepare Students for a World in Flux. Basic Books, 2017.

———. “The New Education and the Old.” PMLA, vol. 133, no. 3, May 2018, pp. 707–14.

Dolan, Emily, and Jonathan Sterne. “Two Campuses, Two Countries, One Seminar.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 25 Oct. 2017, chronicle.com/article/2-Campuses-2-Countries-1/241542.

Duhigg, Charles. “What Google Learned from Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team.” The New York Times, 25 Feb. 2016, nytimes.com/2016/02/28/magazine/what-google-learned-from-its-quest-to-build-the-perfect-team.html.

Ede, Lisa S., and Andrea Lunsford. “Audience Addressed / Audience Invoked: The Role of Audience in Composition Theory and Pedagogy.” The Writing Teacher’s Sourcebook, edited by Edward P. J. Corbett, et al., Oxford UP, 1994, pp. 243–57.

Glass, Erin Rose. “Ten Weird Tricks for Resisting Surveillance Capitalism in and through the Classroom . . . Next Term!” HASTAC, 27 Dec. 2018, hastac.org/blogs/erin-glass/2018/12/27/ten-weird-tricks-resisting-surveillance-capitalism-and-through-classroom.

Gray, Mary L., and Siddharth Suri. Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass. Houghton Mifflin, 2019.

“Guides.” re:Work, rework.withgoogle.com/guides/. Accessed 3 June 2019.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. Routledge, 1994.

Katopodis, Christina. “Dialogic Methods in the Classroom.” HASTAC, 18 Feb. 2019, hastac.org/blogs/ckatopodis/2019/02/18/dialogic-methods-classroom.

———. “Entry and Exit Tickets: A Way to Share in the Intellectual Growth of Students.” HASTAC, 4 Mar. 2019, hastac.org/blogs/ckatopodis/2019/03/04/entry-exit-tickets-way-share-intellectual-growth-students.

———. “A Lesson Plan for Democratic Co-creation: Forging a Syllabus by Students, for Students.” Christina Katopodis, 12 Nov. 2018, christinakatopodis.net/2018/11/12/a-lesson-plan-for-democratic-co-creation-forging-a-syllabus-by-students-for-students/.

———. “Mediating Race: Technology, Performance, Politics, and Aesthetics in Popular Culture.” HASTAC, 16 Aug. 2018, hastac.org/groups/mediating-race-technology-performance-politics-and-aesthetics-popular-culture.

Lang, James M. Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons from the Science of Learning. Jossey-Bass, 2016.

Lunsford, Andrea, et al. “College Writing, Identification, and the Production of Intellectual Property: Voices from the Stanford Study of Writing.” College English, vol. 75, no. 5, 2013, pp. 470–92.

Lunsford, Andrea, et al. Everyone’s an Author. W. W. Norton, 2012.

Morris, Sean Michael, and Jesse Stommel. An Urgency of Teachers: The Work of Critical Digital Pedagogy. Hybrid Pedagogy, 2018.

“Project Oxygen: Eight Ways Google Resuscitated Management.” Impraise, 5 June 2019, blog.impraise.com/360-feedback/project-oxygen-8-ways-google-resuscitated-management.

Rainie, Lee, and Janna Anderson. “The Future of Jobs and Job Training.” Pew Research Center, 3 May 2017, pewinternet.org/2017/05/03/the-future-of-jobs-and-jobs-training/.

Savonick, Danica. “Teaching Race and Gender Theory—A Toolkit.” HASTAC, 13 June 2017, hastac.org/collections/teaching-race-and-gender-theory-toolkit.

Semuels, Alana. “The Online Gig Economy’s ‘Race to the Bottom.’” The Atlantic, 31 Aug. 2018, theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/08/fiverr-online-gig-economy/569083/.

Shor, Ira, editor. Freire for the Classroom: A Sourcebook for Liberatory Teaching. Boynton/Cook, 1987.

Warner, John. Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities. Johns Hopkins UP, 2019.

Wood, Sarah. “Recent Graduates Lack Soft Skills, New Study Reports.” Diverse, 3 Aug. 2018, diverseeducation.com/article/121784/.

Woolley, Anita Williams, et al. “Evidence for a Collective Intelligence Factor in the Performance of Human Groups.” Science, vol. 330, 2010, pp. 686–88.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.Christina Katopodis is a doctoral candidate in English; Futures Initiative Fellow at the Graduate Center, City University of New York; and adjunct instructor at Hunter College, City University of New York. She is the winner of the 2019 Diana Colbert Innovative Teaching Prize, the 2018 Dewey Digital Teaching Award, and the 2018 Digital Dissertation Award. She is completing her dissertation, which examines changing literary insights and representations of human and nonhuman sounds before and after the advent of sound recording technology. Katopodis and Davidson maintain a blog, Progressive Pedagogy, and are collaborating on a book about creating a student-centered learning experience.

Cathy N. Davidson is distinguished professor and founding director of the Futures Initiative at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, and DeVarney Professor Emerita of Interdisciplinary Studies at Duke University. Her most recent book is The New Education: How to Revolutionize the University to Prepare Students for a World in Flux. In 2019–20, she is serving as senior fellow at the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, focusing on the future of the humanities, transforming graduate education, and the importance of community college.

3 comments on “Changing Our Classrooms to Prepare Students for a Challenging World”