From June 2009 to June 2012 I served on the MLA Committee on Contingent Labor in the Profession (CLIP), chairing the committee during my last year. One of the greatest benefits of working on a professional committee of this sort is the opportunity to learn about the profession as a whole, beyond one’s own experience in specific appointments and institutions. Before I served on the CLIP committee, my beliefs about contingent labor had been formed while I taught French in a full-time non-tenure-track (NTT) position at a public university in the Midwest. Some of these beliefs were confirmed during the committee’s work, but I had to revise many of my assumptions as the committee studied national data and grappled with the diversity of experiences in higher education. I came away with a better understanding of what a voluntary membership organization like the MLA can and cannot accomplish on behalf of its members. While the MLA can collect and disseminate information at a national level and advocate certain professional norms, it became clear to me that tangible improvements to contingent employment in departments of English and modern foreign languages could be implemented only at the local level. Accordingly, in this essay I share national perspectives gained from three years of MLA committee work, then present a local illustration of employment practices in the university system where I worked for ten years.

The Committee on Contingent Labor in the Profession was created by the Executive Council in 2009 at the request of the Delegate Assembly of the MLA, and it was constituted through the year 2014, when it is certain to be renewed for a second term. The committee was charged with considering a range of issues, collecting information, and organizing convention sessions and publications regarding NTT faculty members and the departments that employ them. Four years after its inception, I can report that the committee has in fact done all of the above, but from the beginning it was not easy to decide what initiatives to pursue, nor was it obvious what actions would have the most positive influence on the profession.

Institutions of higher education across the United States are extremely diverse, and this diversity was reflected in the selection of our committee. The initial eight people were tenured and nontenured and worked both full- and part-time as instructors and administrators in departments of English and foreign languages. The committee included faculty members from a community college, from top-tier and middle-tier public research universities, from a large private university and a small liberal arts college. Some of us worked in unionized settings, and some did not. We had one Canadian member. There was only one way in which we were not diverse: we had all come through PhD programs. Two of us were ABD in 2009, and the rest held PhDs, whereas national demographics show that only about half of all faculty members in higher education hold the PhD. Most faculty members are now NTT and hold terminal MAs or other degrees (2004 National Study of Postsecondary Faculty [qtd. in Laurence]).

That we came from different institutions and appointments was immediately apparent as committee members introduced themselves and spoke about their working lives and concerns. We each had a different vocabulary: our Canadian colleague talked about “sessional faculty,” and the titles lecturer and adjunct carried different rights and responsibilities on different campuses. Committee discussions revealed that the highly unionized Canadian system did not correspond easily to the United States system, even in United States settings where unions were active. We all had varying degrees of access to information about our own institutions: committee members working at nonunionized public universities frequently had easy access to staffing information and other institutional data, whereas those working in unionized settings or private schools had less access. What each of us considered to be progress or good news for contingent labor varied considerably. When a community college administrator proudly said that her school had just eliminated a number of NTT positions to create a larger number of tenure-track positions with benefits, a committee member working off the tenure track replied that this scenario was his worst nightmare, because it meant that many like him were likely to be out of a job. Finally, what each of us hoped to accomplish on the committee varied: committee members with administrative responsibilities, accustomed to working through an institutional framework, returned more frequently to the idea of establishing practical recommendations related to hiring and evaluating NTT faculty members, whereas those who did not have access to administrative channels expressed skepticism that change could be effected through such institutional means—they hoped rather to find ways to empower individual faculty members. Given these differences, it was not easy to decide what action the committee should take to fulfill its charge.

One of the first steps we took was to inform ourselves about the national context for contingent labor. David Laurence, director of the ADE, was the MLA staff member assigned to our committee. As the MLA’s resident statistician, Laurence is adept at using government data sources to uncover pertinent and important information about the profession. At the committee’s first meeting in 2009, he reminded us that our experience on individual campuses was deep but narrow and not necessarily representative of national trends. To help us gain an overview of contingent labor, he presented us with an extensive PowerPoint presentation that included employment figures drawn from the Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) and National Survey of Postsecondary Faculty (NSOPF).

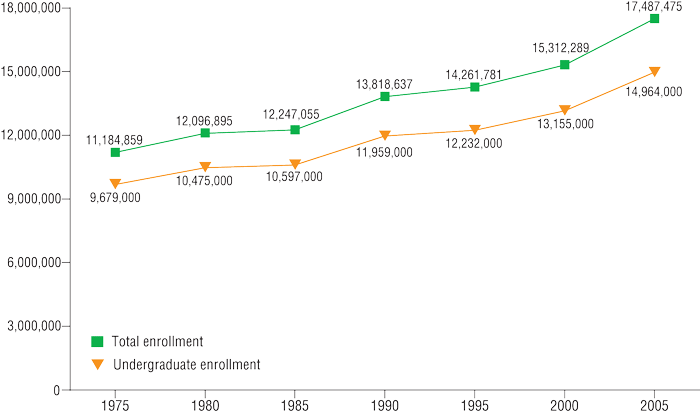

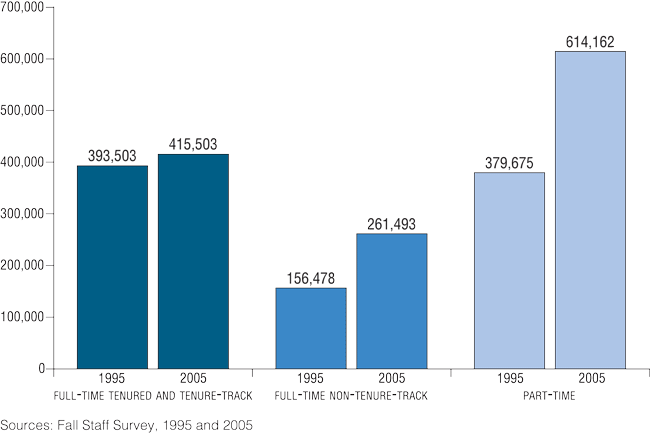

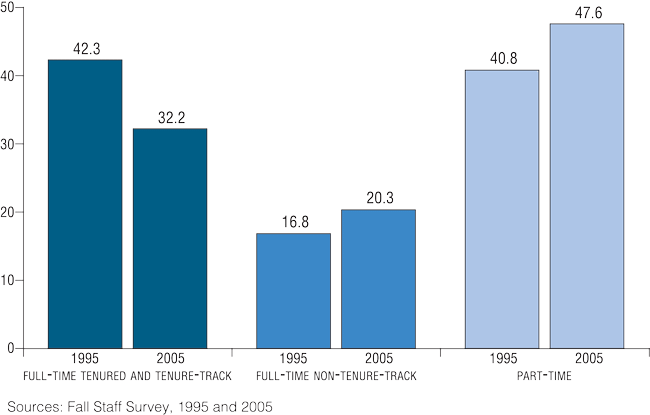

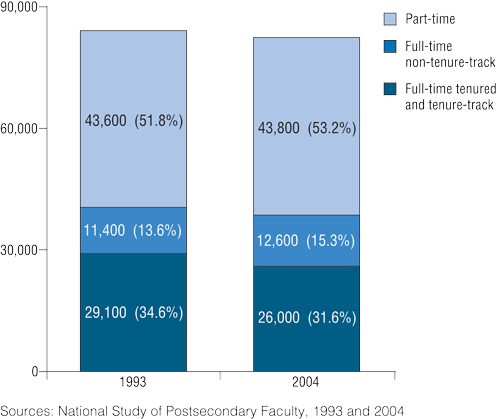

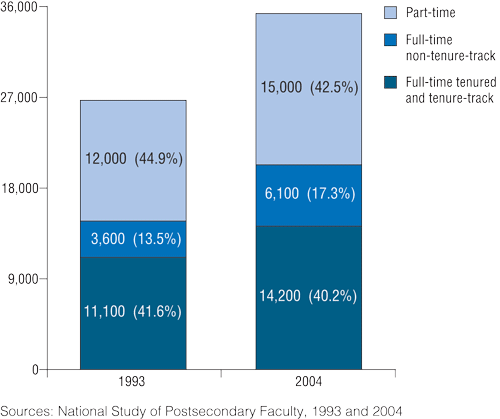

We learned that although it is very common to talk about the declining number of tenure-track faculty members in the United States, data show that overall there has been a decline in percentage but not in number (fig. 1b and fig. 2). Student enrollments have steadily risen in the United States since 1975 (fig. 1a). One would expect that there would be an increase in tenure-track faculty members to meet the instructional needs of these students, and that is indeed the case. The number of these teachers has risen since 1995 but not as fast as the number of NTT faculty members, of whom part-timers increased more than those working full-time. There are some notable disciplinary differences. English experienced a decline in the number of tenure-track professors (from 29,100 to 26,000 between 1993 and 2004 [fig. 3]). In foreign languages, there was an increase in that number (from 11,100 to 14,200 between 1993 and 2004 [fig. 4]). In both fields, however, there was a large increase in the number of NTT faculty members.

Figure 1a. Change in Student Enrollments, 1975–2005 ↩

Figure 1b. Change in the Number of Faculty Members in Different Employment Categories ↩

Figure 2. Change in the Percentage of Faculty Members in Different Employment Categories ↩

Figure 3. Estimated Population of Faculty Members in English in Different Tenure and Employment Statuses ↩

Figure 4. Estimated Population of Faculty Members in Foreign Languages in Different Tenure and Employment Statuses ↩

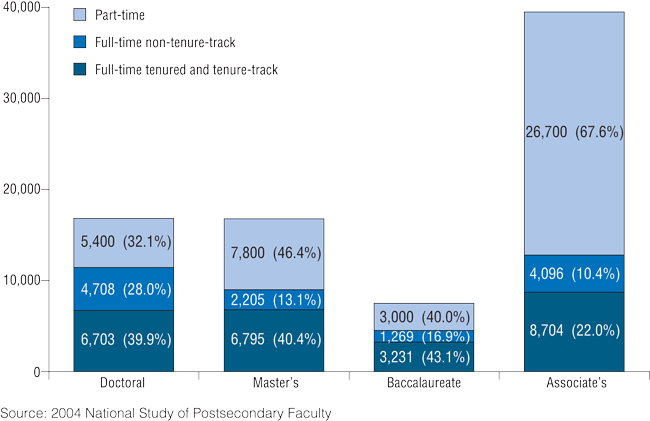

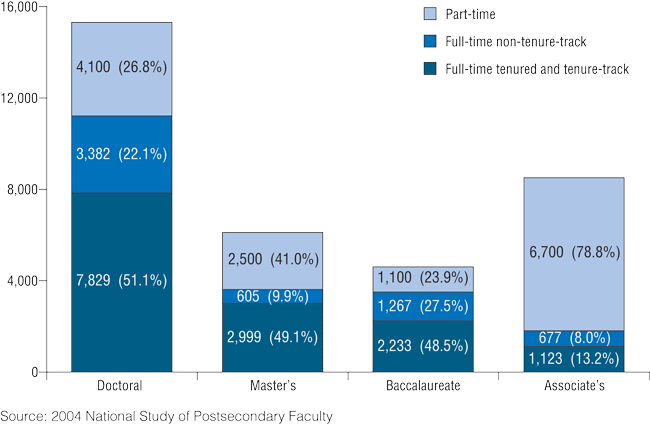

The total number of English faculty members teaching in two-year institutions, for every employment status and Carnegie classification of institution, is nearly equal to the number of English faculty members teaching at doctoral, master’s, and baccalaureate institutions combined (fig. 5). Significantly, most of those teaching at two-year schools—68%—are teaching part-time, off the tenure track, which suggests that efforts focused on community colleges will affect the lives of the largest number of NTT faculty members. The committee did not choose this route, however, probably because so few of us were involved with community colleges and because we knew there was considerable work to be done in the four-year institutions where we worked. Nonetheless, programs that grant MAs and PhDs in English should keep these figures in mind when thinking about where their graduates end up teaching.

Figure 5. Distribution of Faculty Members in English, by Employment Status and Institutional Type ↩

If we look at comparable charts for faculty members in foreign languages, we see that employment outcomes are quite different (fig. 6). Nationwide, fewer foreign language than English faculty members teach in a two-year institution. It also appears that foreign language faculty members are less likely to wind up in part-time NTT positions than English faculty members (with the exception of two-year institutions, where the percentage of part-time faculty members is higher for foreign languages than for English). Individual experience may not follow the national norm: I was working in a language department that had gradually become staffed almost exclusively by NTT faculty members, and before serving on the MLA committee I thought that my department represented a general trend in the discipline.

Figure 6. Distribution of Faculty Members in Foreign Languages, by Employment Status and Institutional Type ↩

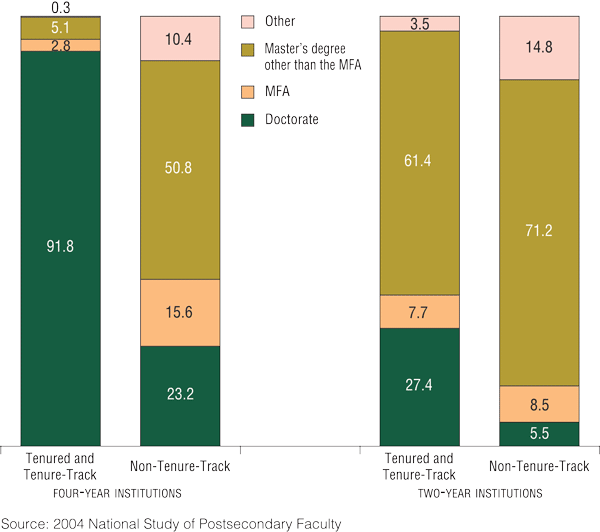

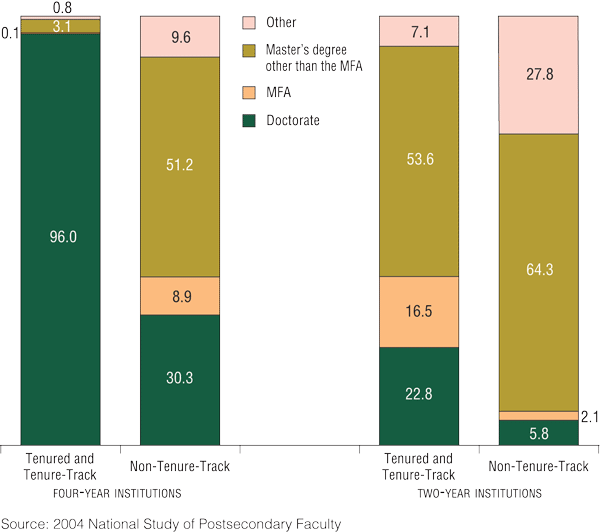

In the early days of our work as a committee, discussions occasionally touched on whether we should issue a call for conversion to tenure for all NTT faculty members. This impulse was checked, however, by information on the types of terminal degrees held by faculty members on and off the tenure track. In both English and foreign languages, more than 90% of tenure-track faculty members in four-year institutions hold the PhD, whereas less than a third of NTT faculty members in four-year institutions have this credential. This same proportion holds for faculty in two-year institutions (fig. 7 and fig. 8). This difference in credentials was an important consideration for the committee: it meant that to convert NTT faculty members to the tenure track, the credentials required for tenure-track positions on most campuses would have to be changed. In the end, we felt that tackling the definition of tenure was simply too large an issue for us to deal with and so channeled our energies in different directions.

Figure 7. Percentage of Faculty Members in English On and Off the Tenure Track, by Highest Degree Held and Institutional Type ↩

Figure 8. Percentage of Faculty Members in Foreign Languages On and Off the Tenure Track, by Highest Degree Held and Institutional Type ↩

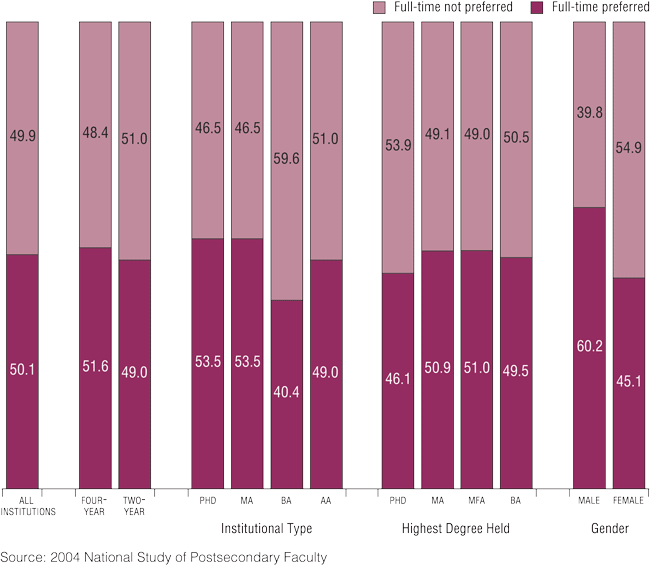

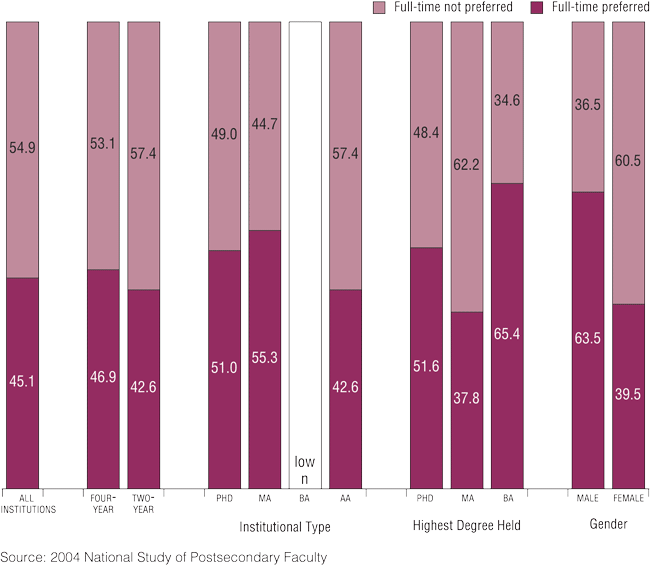

We also wondered whether it would be desirable to issue a call for reducing the number of part-time faculty positions and creating more full-time positions with benefits. Data culled from the 2004 NSOPF made us reconsider: they show the percentage of part-time faculty members in English and foreign languages who would prefer full-time employment. Overall, roughly half in both fields reported that they wanted to keep working part-time. There was a notable difference in this response by gender. About 60% of male part-time faculty members in both fields wanted to move to full-time work, but only about 40% of female part-time faculty members did (fig. 9 and fig. 10). These figures were a reminder to the committee that part-time employment meets the needs of many faculty members. A general call to convert part-time positions to full-time would therefore not be universally appreciated.

Figure 9. Percentage of Part-Time Non-Tenure-Track Faculty Members in English Who Would Prefer a Full-Time Position ↩

Figure 10. Percentage of Part-Time Non-Tenure-Track Faculty Members in Foreign Languages Who Would Prefer a Full-Time Position ↩

The data drawn from IPEDS and the NSOPF confirmed the diversity of experience that was represented among our committee members. Our problem was to identify initiatives that would be relevant for the profession as a whole, for both instructors of English and of foreign languages, in all types of appointments and institutions. Between 2009 and 2012, we undertook the following activities:

- We revised “MLA Recommendation on Minimum Per-Course Compensation for Part-Time Faculty Members” and provided a justification for the recommended figure, to explain the rationale for what remains a largely aspirational salary ($7,090 for a one-semester, three-credit course).

- We produced a policy document titled Professional Employment Practices for Non-Tenure-Track Faculty Members: Recommendations and Evaluative Questions, a nonprescriptive checklist designed to help departments assess and develop employment policies and to be useful to faculty members and administrators in different institutional settings.

- In an attempt to make the MLA convention more accessible to NTT faculty members and recruit new members, we invited a limited number of local NTT faculty members to a focus group social event at the 2012 MLA convention in Seattle. This initiative was repeated in Boston in 2013. In both cases conference registration fees were waived for attendees, and the committee gained valuable insights from the comments of its guests. It is expected that this event will be repeated at each annual convention in years to come.

- We organized a special joint issue of the ADE Bulletin and ADFL Bulletin that will appear later in 2013. The issue presents several case studies of employment practices and initiatives related to contingent labor across the country.

The committee’s work continues under Karen Lentz Madison, the 2012–14 chair. In its most recent initiative in fall 2013, the committee began to make contact with accrediting agencies in hopes of encouraging them to take academic staffing practices into consideration during the accreditation process.

We found it difficult to effect tangible change on contingent labor issues at the national level, but there are examples of local initiatives where an institution implemented an improved employment policy—usually driven by the particular culture of a campus or department. One example comes from the university system in Missouri, where I worked for ten years. It is imperfect but pragmatic, and it was developed with input from human resource officers whom Maria Maisto, president of the New Faculty Majority, has identified as promising allies in efforts to improve academic staffing practices.

The Missouri model grew out of a new titling system for NTT faculty members that was developed through a collaboration begun in 2004 between the Interfaculty Council of the four campuses of the University of Missouri system (Columbia, Saint Louis, Kansas City, and Rolla) and Deborah Noble-Triplett, assistant vice president for academic affairs. Noble-Triplett holds a PhD in industrial-organizational psychology and previously served on the business faculty of the University of Missouri, Kansas City, where her research dealt with human resource issues in the private sector. When the council decided to acknowledge the contributions of NTT faculty members and improve inconsistencies in the employment practices affecting growing numbers of them in the University of Missouri system, Noble-Triplett was assigned to facilitate the necessary gathering of information, understand the diversity of experiences of this faculty population, and work with the council and with the campus provosts to develop new policies.

After two years, in November 2006, this collaboration resulted in a change to the rules and regulations of the university. Executive guideline 35 established four categories of NTT appointments, where there had been none before: research, teaching, clinical, and extension (“310.035”). (In the humanities, most are on the teaching track.) The ranks in each category follow the same logic as the tenure track and have similar titles. On the teaching track, for example, an instructor can be promoted from assistant teaching professor to associate teaching professor and finally to teaching professor. But while tenure-track faculty members must be active in three areas—teaching, research, and service—NTT faculty members are expected to be active in only two: teaching and service.

Executive guideline 35 goes on to specify many conditions of employment for NTT faculty members. It imposes clearly defined expectations for each position from the day of hire, states that searches for NTT faculty members should be similar to those done for tenure-track colleagues, provides options for contract length, and requires units to develop guidelines for annual performance evaluations based on a dossier rather than teaching evaluations alone. The guideline also specifies rules and time lines for reappointment decisions, provides for the creation of NTT promotion committees on each of the four Missouri campuses, and guarantees the academic freedom of NTT faculty members and urges their participation in faculty governance.

All these features of the Missouri model involve general employment practices that can be implemented regardless of discipline. They may seem self-evident, but before 2006 many departments had no policies of the sort. Whereas staff appointments and tenure-track appointments had always been highly regularized in the Missouri system, NTT faculty appointments had been left to individual department chairs who usually had little experience with employment law or conventional protocols for hiring and evaluating employees. This is where the expertise of the human resource office was particularly helpful.

I see several advantages to the Missouri guideline for NTT faculty members:

- The titling system is cheap to implement, and costs are generally slow to accrue.

- To a considerable extent the guideline has standardized appointments across the University of Missouri system, so that all NTT faculty members have an annual review and a contract.

- The possibility now exists for three-year contracts for some NTT faculty members, although this option has been discouraged in some units since the recession of 2008.

- Even without three-year contracts, a history of positive annual reviews and successive promotions contributes to a feeling of job security and gives a long-term career perspective for NTT faculty members.

- The new titles (e.g., assistant teaching professor instead of lecturer) are perceived as adding prestige and have helped in the recruitment of new faculty members.

There are several disadvantages to the guideline:

- It takes time for faculty members to document their NTT colleagues’ performance or evaluate their progress toward promotion on an annual basis. The rewards or consequences of NTT promotion are limited in comparison to those of the tenure track. For example, there is no raise stipulated for promotion. Many NTT faculty members who are promoted do receive a raise that is separate from and greater than the annual merit raise, but there is no guarantee of it.

- That the NTT titling system re-creates the hierarchy that exists in the tenure system is unattractive to some NTT faculty members, who found the former lack of hierarchy to be more collegial.

- Because of the decentralized approach to implementation, the rights and responsibilities granted to NTT faculty members can differ dramatically from one department to the next. (I’m not sure how this inequity can be avoided, since universities are highly decentralized organizations.)

- These NTT positions do not reward research unless a faculty member is on the research track. There are legal reasons for this division, but in practice many faculty members on the teaching track have the same credentials as research faculty members and would like to be able to pursue projects for which they were trained. In the absence of support such as sabbaticals and course releases or recognition in the form of raises and awards, many are unable to pursue research projects on a continuing basis.

- The guideline does not yet address the working conditions of other groups of NTT faculty (e.g., part-time faculty members).

There have been some unexpected outcomes since the implementation of this new system in 2007. Almost immediately, the definition of faculty became more inclusive. When the Missouri system instituted paid family and medical leaves for faculty members in 2008, both those who were on the tenure track and those who were not were covered by the provision. NTT faculty members have also become more visible. On the Saint Louis campus, they have begun to serve on review teams for five-year departmental reviews, and these teams frequently meet with full-time and part-time NTT faculty members, just as they meet with tenure-track faculty members of different ranks. The experience of NTT faculty members is thus documented and assessed in official five-year review reports, becoming part of the public record.

Much work remains to be done on the University of Missouri campuses regarding academic staffing and the employment of NTT faculty members. The improvements I witnessed between 2003 and 2013, however, make me cautiously optimistic for the future, as do the many nationwide initiatives that came to my attention while I served on the MLA Committee on Contingent Labor in the Profession. I confess that, despite all the work that the committee put into its early endeavors, I have only a thin feeling of accomplishment. I am uncertain whether any of these activities has concretely improved the lives of faculty members working off the tenure track. I encourage colleagues around the country to take advantage of the documents generated by our committee and others at the MLA and to use them to implement change on their own campuses. To this end, I would like to draw attention to the resources available in the MLA Academic Workforce Advocacy Kit, where a wealth of information about current models and practices for academic staffing has been assembled for the benefit of colleagues in the profession. These tools can be used to improve the way academic labor is managed in a variety of institutional settings.

Note

I would like to thank David Laurence, director of ADE, for the figures included in this essay. Many thanks as well to Deborah Noble-Triplett, assistant vice president for academic affairs for the University of Missouri System, for helping me understand the Missouri guidelines for non-tenure-track faculty appointments.

Works Cited

Laurence, David. “A Profile of the Non-Tenure-Track Workforce.” ADE Bulletin 153–ADFL Bulletin 42.3. Forthcoming.

“MLA Recommendation on Minimum Per-Course Compensation for Part-Time Faculty Members.” Modern Language Association. MLA, Apr. 2013. Web. 12 Aug. 2013. <http://www.mla.org/mla_recommendation_course>.

Professional Employment Practices for Non-Tenure-Track Faculty Members: Recommendations and Evaluative Questions. Modern Language Association. MLA, June 2011. Web. 12 Aug. 2013. <http://www.mla.org/pdf/clip_stmt_final_may11.pdf>.

“310.035 Non-Tenure Track Faculty.” Collected Rules and Regulations. Inside UM System. Curators of U of Missouri, n.d. Web. 22 July 2013. <http://www.umsystem.edu/ums/rules/collected_rules/faculty/ch310/310.035_non-tenure_track_faculty>.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.Posted October 2013