In August 2013, a few months before the twentieth anniversary of their armed uprising against the Mexican government on 1 January 1994, the Zapatistas decided to throw a party. Subcomandante Insurgente Moisés sent out word via the Zapatista Web site to “quienes se hayan sentido convocados” (“those who feel summoned”) to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the five caracoles (“autonomous municipalities”—literally, “snail shells”), each with its own rotating governing organization of women and men, the Council of Good Government (Junta de Buen Gobierno [JBG]) (“Fechas”).

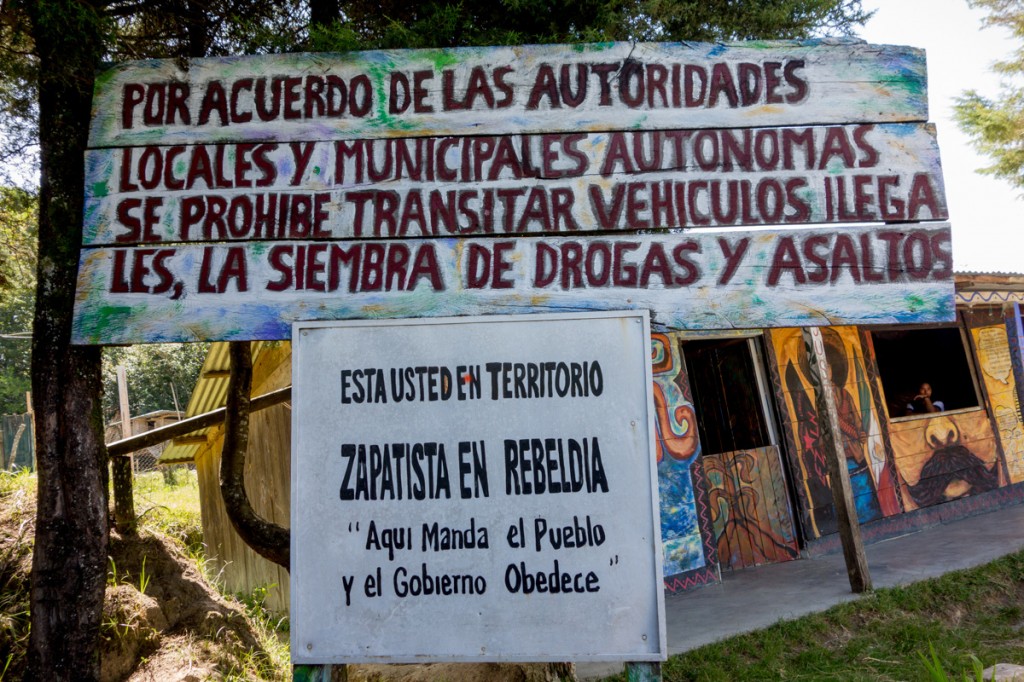

The caracoles provide basic services to the Zapatista communities, who are predominantly Mayan and receive nothing but trouble from the Mexican government. On the rainy night of the party, vans, trucks, and cars lined up far along the road that goes past Oventic, the caracol closest to San Cristobal de las Casas, Chiapas. A sign on the road said:

ESTA USTED EN TERRITORIO

ZAPATISTA EN REBELDIA

“Aquí manda el pueblo

y el gobierno obedece”

YOU ARE IN ZAPATISTA REBEL TERRITORY:

“Here the people decide, and the government obeys.”

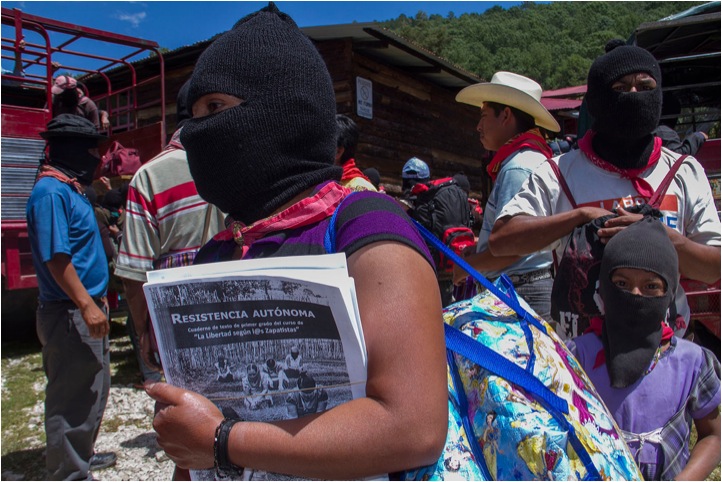

Past the unassuming metal gates that separate Oventic from the rest of Mexico, music reverberated from the loudspeakers. Standing in the pouring rain, the Zapatista men and women wearing ski masks and paliacates (“scarves”) asked people for their IDs. We, the visitors, waited under the tarp outside the Che Guevara gift shop and snack bar that bridges the caracol and the highway. Families and groups of indigenous peoples steadily entered. Some bought soft drinks and food at the entrance before moving past us toward the party. Alcohol is prohibited in all Zapatista communities. While some Mayans wore Western clothing—pants and sweatshirts—many were dressed in the native clothing of their various villages. The women from Chamula wore, against the cold and rain, their local thick black lambskin skirts and lovely embroidered tops under thin acrylic sweaters in all colors. Those from Zinacantán wore the beautiful blue-and-purple tops of their village. There were many other patterns from other regions, but I could not identify them (see Morris). To this day, the embroidery communicates meaning among indigenous peoples capable of deciphering them—“hidden transcripts,” as James C. Scott calls them (4–5), but in textiles. Bodily practices and the aesthetics of the everyday, for the Zapatistas, are never removed from politics. Sartorial style, especially the ski mask or the paliacate, the red bandana they wear, identified them all as Zapatista.

On view, from where I waited, were the contradictions and promise of the globalization and alter-globalization moments. Those who enjoy the economic and social mobility to travel come to visit those who fight to stay on their lands; Mayans in traditional clothing buy Coca-Cola in the Che Guevara snack bar while we Westerners buy their embroideries. The man who took our information wanted to know where we were from and why we wanted to be there. “To celebrate,” I said.

Indigenous resistance strategies have changed and adapted over the decades, some would say centuries, since the resisters started down el camino largo (“long road”) to autonomy. The Zapatistas have tried and experienced everything: the grassroots organizing of the 1980s; the armed warfare of early 1994; negotiations with the “bad” government, which produced the San Andrés Accords in 1996 (San Andres Accords), guaranteeing autonomy and rights to indigenous peoples; loss of faith in the Mexican government when it failed to honor the accords; the formation of an alternative “good” government and autonomous administrative centers in 2003; national marches throughout the country to make visible the Zapatista claims to justice and dignity (Otro jugador); closing the caracoles off from the world; opening them to national and international supporters; and now the invitation to celebrate and attend their escuelitas (“little schools”). Thousands of visitors came to Chiapas that August to live in the caracoles for a week and learn the Zapatista ways of living and thinking.1 The resistance movement works both on the macro and micro political levels: the celebration testified to the years of armed resistance against the Mexican government while the escuelitas worked in the micro arena of everyday politics in people’s homes.

Having finally been admitted, we walked down a slippery road to the official ceremony. A long line of civic representatives from the various Zapatista communities walked through the rain and stepped onto the platform—about thirty or forty men and women in traditional indigenous dress. Several young Zapatistas marched with the Mexican and EZLN flags (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional [“Zapatista Army of National Liberation”]) around the courtyard and stood at attentipon. The national anthem came over the loudspeakers, and young Zapatistas raised their arms in military salute. They too are “mexicanos al grito de guerra” (“Mexicans at the cry of war,” Mexico’s belligerent national anthem). The opening ceremony was all about military gestures. The Zapatistas, vulnerable not only as predominantly indigenous people but also as people living in active opposition to the national government, know that they need to be ready.

I focus here on vulnerability not as a condition or state of being but rather as a doing and a relationship of power. The Zapatistas’ vulnerability has been structurally imposed and economically organized from colonial times until the present. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was simply the last straw. But they adapt, they say, “para no dejar de ser” (“in order not to cease to be”) historical beings (“Nosotros”). The bottom line, using John Holloway’s terminology, is that indigenous communities’ “power-to” live, work, and flourish has been under constant attack by the government’s “power-over” their life, work, and well-being (12). How can resistance counter this making vulnerable?

The Zapatista’s political project, I saw for the first time, was not indigenous in form or content; it was the age-old struggle for good government. The entrance to the rebel territory marks the line between two interconnected political systems—both performative, both masked. One, the bad neoliberal government (I agree with the Zapatistas that it is bad), is characterized by violence, corruption, and greed. The other is good in that it examines the basic mechanisms of existing power—power not as a thing one has but as a practice of social relations—and asks, Who exerts the power? Who decides? Who gets left out? They then transform those practices and relationships into their core principles:

- participatory assemblies: “The people decide.”

- nondiscrimination: Zapatismo is nonnormative. Although the Zapatistas were long exploited as indígenas, their strategy refuses identity politics, be it ethnic, religious, gender, sexual, class, or linguistic. Their goal, again, is not about being but about doing, about joining the struggle for indigenous rights.

- collaboration: “Para todos, todo. Para nosotros, nada” (“For everyone, everything. For us, nothing”). Zapatismo values individual rights but acknowledges that individuals cannot do it alone and must exist as part of a collective: “Solos no podemos” (“Alone we can do nothing”).

Resistance here does not mean a rejection of government or a proposed outside to the political. It is a durational performance, and the Zapatistas are masters of the genre. By durational, I mean that the Maya, like many other Native American groups, have weathered attacks for hundreds of years. Durational is also the defining feature of the Zapatista resistance. Many sporadic uprisings and acts of contestation by indigenous peoples take place constantly throughout the Americas—we can think of the Idle No More movement in Canada, the ongoing Mapuche conflict in the southern tip of Chile and Argentina—but the Zapatistas have led an armed uprising and created their own communities and governing structures. Their struggle has eclipsed, as scholars belonging to other Native groups have acknowledged (e.g., Rivera Cusicanqui), other movements both in terms of scale and length of rebellion. The Zapatistas refuse to cede both the mechanics and the idea of state to self-serving political parties (Abrams). They will not be othered. They acknowledge the historical-political causes of their marginalization but manage its effects and affects. The anonymity imposed on them is performed powerfully through their masks; the silencing enforced on them is enacted through their massive silent marches. They call attention to their mask as one more in a complex system of masking, where politicians disguise themselves and their deeds behind imperatives of the state. When delegates from the Mexican government refused to negotiate with the Zapatistas unless they removed their masks, the Zapatistas answered, “But the state is always masked.” At least, the Zapatistas said, the Zapatistas knew that they were masked (Taussig 246).

That the performative force of these gestures resonates nationally and internationally is the only reason most of them are alive today.

Zapatistas have taken over the functions associated with state systems (Abrams 58): health care, education, management of resources, self-defense and control of the territory. They claim the strategy, the proper (propre), the space and time that belong to them, which as de Certeau puts it, “[serve] as the basis for generating relations with an exterior distinct from it” (xix). They decide who enters their territory, when, and under what circumstances. They control the entrances and the exits. Having handed over our papers, we wait for permission to proceed. We are entering their time zone.

Although the struggle to form a good government is not indigenous, the value system through which that struggle takes place most certainly is. Zapatistas inhabit an age-old Mayan system of equivalences, deep-rooted connectivity, and mutual recognition. Human beings, corn, snails, mountains, rain, and all else have their ch’ulel, the animation and interconnectedness of all things, human and nonhuman. A Zapatista who met with me during those days put it this way: “Ch’ulel refers to the life in everything. It’s the presence that constructs and completes everything that exists in the universe and that gives it its importance,” its dignity and “grandeur.” Mesoamericans started developing corn ten thousand years ago, and as a consequence they are the people of corn.

Monsanto wants to grow, not kill, corn, the transnational corporation claims, but it will kill corn’s ch’ulel. Genetically modified corn will become one more dead thing in the capitalist production of dead things. The challenge is “how to create a world based on mutual recognition of human dignity, on the formation of social relations which are not power relations” (Holloway 8). One way has been through the affirmation of an inclusive we, a nosotros that dialogues with other nosotros, other groups of people able to represent themselves. In our meaning-making systems we might imagine this communication as a discussion of occupiers from Occupy Wall Street with other Occupy groups that have organized themselves autonomously.

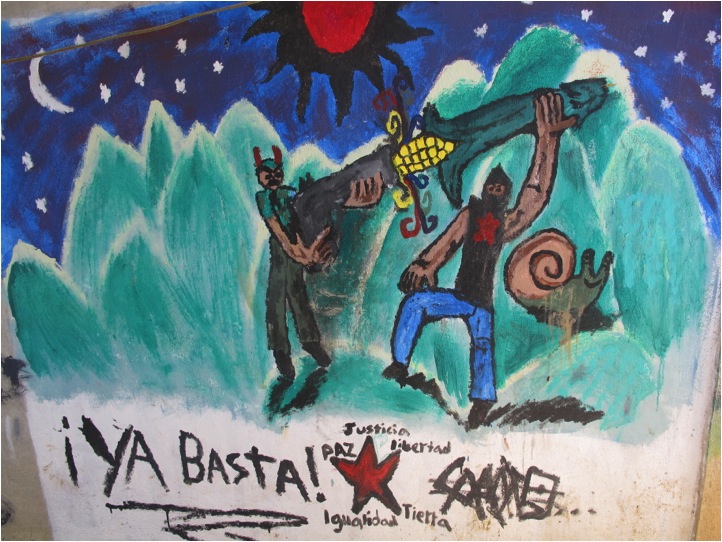

The caracol, as a social formation, enacts the system of equivalences. The paintings and sayings of each caracol encapsulate an entire worldview. Images of snails, often wearing humorous Zapatista masks, make their way into most of the murals, paintings, and textiles. Not only do the Zapatistas honor the slow and steady pace of the snail, the patience and expenditure required for all doing, but the snail shell serves as the design layout for their communal lands that spiral open from tight administrative centers. The unassuming snail also represents war in the classical Mayan glyphs,2 the war the Maya have long waged against colonial and imperialist masters and now with the bankers of those masters (Chase Manhattan made the elimination of the Zapatistas a precondition for a bailout after the economic disaster precipitated by NAFTA in 1995).3

At the celebration, a woman identified only as a member of the JBG addressed the crowd in Spanish: “Compañeras, compañeros, hermanas y hermanos de la sociedad civil, nacional e internacional” (“Companions, brothers and sisters of the national and international community”).4 Gender parity has been central to the movement even before the Revolutionary Law for Women passed in 1993. This parity is reflected not only in all governing roles, official positions, and educational practices but also in the very language: no word with a masculine ending for a person stands without its feminine counterpart, so hermanas (“sisters”) accompanies hermanos (“brothers”). The compañera from the JBG spoke of the struggles the movement has endured over the years: “It hasn’t been easy, these ten years of practice and building our autonomy. . . . It hasn’t been easy for many reasons, such as the lack of experience or lack of training in governing and self-governing.” But the need for resistance continues, she made clear, confronted as the Zapatistas are by a government that continues to deny them rights and liberty and that wants to take their lands. She said that they continue to learn how to resist and work for democracy, though the fruits of the struggle will not be reaped in their lifetime. She asked people of good heart and goodwill that compose civil society to support their struggle.

Was she referring to us, the visitors?

After the compañera finished speaking, another member of the JBG from another region took the microphone and delivered the same speech in Tzeltal. When he was done, another delivered it in Tzotzil. The speeches seemed interminable to me in the downpour, and I looked down at my ruined shoes in dismay.

Soon the speeches were over, and the flags were marched ceremoniously out of the central space. The next few minutes were all “¡Viva!,” “Long live the Escuelita Zapatista!,” “Long live national and international civil society!,” “Viva the grassroots communities!,” “¡Viva el subcomandante insurgente Marcos!,” “¡Viva el subcomandante insurgente Moysés!,” “¡Viva el comite clandestino revolucionario indígena!” (“Viva the clandestine indigenous revolutionary committee!”), “¡Viva el Ejercito Zapatista de Liberación Nacional!,” “¡Viva Chiapas!,” “¡Viva México!” The vivas got louder and louder. Joyous music started up and was followed by clapping. Soon all the representatives had marched off the podium, a long line of women and men walking single file, one after another, in their fine indigenous clothing. They moved quickly, though formally, through the pouring rain up the long road to the entrance of the caracol. The music, very tinny and brassy corridos (“ballads”) set to polka-type beats, sang of heroic opponents to bad governments.

Then music came on over the speakers and an emcee called people onto the basketball court, now a dance floor. Couples came forward with black plastic tarps over their heads, ski masks covering their faces, and moved slowly, rhythmically to the music. The people I had come with joined in, dancing raucously and happily in the company.

To return to the Zapatista’s question: What were we doing there? Were we tourists? Maybe some of us there were wannabe revolutionaries. Another way to put it is that the party brought together a broad range of people, many of them from other activist networks and grassroots movements. Those accepting Moises’s invitation became a WE by attending.5 This performative gesture initiated a dialogue among these WE, a dialogue that protected the Zapatistas from extermination but that inspired us as well. Activists from decolonial, antiglobalization, environmental, and other movements continue to be inspired by the Zapatistas. WE also serves as a vital addition, a third part, to the binary established by the good and bad governments, in the creation of the civil society that determines who lives and who dies. Systems produce vulnerability, and other systems, networks, and equivalencies can be mobilized to offset some of the debilitating effects and affects. I came to “listen and learn,” as Subcomandante Marcos good-naturedly asked of us (Subcomandante Marcos), but I know too how much I have to unlearn in order to listen.

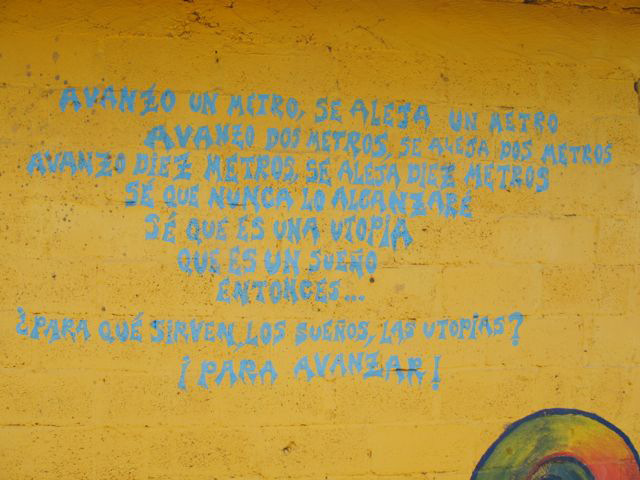

The rain, the mud, the poverty does not seem to quell or diminish the pride or determination of the Zapatistas. According to accounts they cite, Zapatista communities have achieved higher standards of health and education than other indigenous communities in Mexico. But Chiapas is still, twenty years after the uprising, one of the poorest states in the nation. It has more inequality now than then and higher rates of illiteracy (Ríos). Carlos Monsiváis, writing as he accompanied the Zapatistas on their 2001 march for dignity, noted that given the discrimination in Mexico, the obvious and indisputable call for education, food, health, and land seems utopian.6 The more the Zapatistas move forward, the farther the ideals of social justice seem to get away from them. But they keep moving. My experience in the caracol near San Cristobal de las Casas suggests to me that the sense of dignity palpable in the Zapatistas offsets many hardships. As they showed us, they make their own decisions and rules. Those who seek to interact with them need to abide by those decisions and rules. When the Zapatistas allow or invite us to enter their territory, they are hoping that we will act as witnesses and transmitters of their existence, their resistance, and their worldview. I say worldview rather than ideology because they are pragmatists, not ideologues. The evening celebration demonstrated that all indigenous peoples committed to resistance against bad government are welcome, regardless of the religious, linguistic, and regional tensions that often separate groups. Indigenous Catholics, Evangelicals, and even Muslims may fight one another throughout the state, but here they danced together.

And all night and throughout the week, the Mexican air force buzzed the caracoles, just in case we had forgotten that they could.

(Painted on the wall in Oventic, Chiapas)

Avanzo un metro, se aleja un metro

Avanzo dos metros, se aleja dos metros

Avanzo diez metros, se aleja diez metros

Sé que nunca lo alcanzaré

Sé que es una utopía

Que es un sueño

Entonces…

¿Para qué sirven, los sueños, las utopías?

¡Para avanzar!

I advance a meter and it advances a meter

I advance two meters, and it advances two meters.

I advance ten meters, and it advances ten meters

I know I will never catch up

I know it’s a utopia

That it’s a dream

So

What good are dreams? utopias?

To keep us advancing! (my trans.)

Notes

This essay is dedicated to José Esteban Muñoz, friend, colleague, and a cruiser of utopias.

The Zapatista Web site is http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2013/03/17/fechas-y-otras-cosas-para-la-escuelita-zapatista/. For more background information on the Zapatista movement, see Womack; Saldaña-Portillo. ↩

Stross notes the importance of the land and water snails in Mayan glyphs and the significance in their association with the earth and also with war: “Because both land snails and water snails are found in the Maya area and have different names, one cannot be sure whether we are dealing with the snail as earth or as underworld, but the ‘war’ expression probably indicates a land snail” (105). ↩

“The [Mexican] government will need to eliminate the Zapatistas to demonstrate [its] effective control of the national territory and of security policy” (Roett). ↩

I translated this statement from a video of the event; see also Gil and Mandujano. ↩

The Zapatistas and the artists working with them refer to these collectivities as WE. ↩

“Reconocimiento de los derechos a la educación, la vivienda, la salud, la tierra (a fuerza de discriminación, lo obvio, lo indiscutible, se vuelvo lo utópico)” (34). ↩

Works Cited

Abrams, Philip. “Notes on the Difficulty of Studying the State.” 1977. Journal of Historical Sociology 1.1 (1988): 58–89. Print.

Certeau, Michel de. The Practice of Everyday Life. Trans. Steven Randall. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984. Print.

“Fechas y otras cosas para la escuelita zapatista.” Enlace Zapatista. Enlace Zapatista, n.d. Web. 21 Feb. 2014.

Gil, José, and Isaín Mandujano. “Una década de caracoles.” Proceso 25 Aug. 2013: 34–36. Print.

Holloway, John. Change the World without Taking Power: The Meaning of Revolution Today. London: Pluto, 2002. Print.

Monsiváis, Carlos. EZLN: Documentos y comunicados 5. Círculo Ometeotl. Círculo Ometeotl, 2000–01. Web. 22 Feb. 2014. Colección problemas de México.

Morris, Walter. A Textile Guide to the Highlands of Chiapas / Guia textil de los altos de Chiapas. Chicago: Independent Publishers Group, 2012. Print.

“Nosotros: Interview with a Zapatista.” Interview by Diana Taylor and Jacques Servan. San Cristobal de las Casas, Aug. 2013.

El otro jugador: La caravana de la dignidad indígena. Ed. Ramón Vera Herrera. Mexico: La Jornada, 2001. Print.

Ríos, Viridiana. “Chiapas, peor que ayer.” Nexos. Nexos, 1 Jan. 2014. Web. 22 Feb. 2014.

Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia. “Micropolítica y zonas de autonomía en los Andes.” Andrés Bello Chair Lecture, King Juan Carlos of Spain Center, New York U, Feb. 2014. Address.

Roett, Riordan. “The Chase Manhattan Memo—Feb 9, 1995.” New Stuff. The Thing, n.d. Web. 3 Mar. 2014.

Saldaña-Portillo, María Josefina. The Revolutionary Imagination in the Americas and the Age of Development. Durham: Duke UP, 2003. Print.

San Andres Accords, January 18, 1996. Trans. Rosalva Bermudez-Ballin. The Struggle Site. Flag.blackened.net, n.d. Web. 21 Feb. 2014.

Scott, James C. Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts. New Haven: Yale UP, 1990. Print.

Stross, Brian. “Classical Maya Directional Glyphs.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 1.1 (1991): 97–114. University of Texas. Web. 22 Feb. 2014. <http://www.utexas.edu/courses/stross/papers/DirectionalGlyphs.pdf>.

Subcomandante Marcos. “Malas y no tan malas noticias.” Enlace Zapatista. Enlace Zapatista, Nov. 2013. Web. 26 Feb. 2014. <http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2013/11/03/malas-y-no-tan-malas-noticias/>.

Taussig, Michael. Defacement: Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1999. Print.

Womack, John, Jr. Rebellion in Chiapas: A Historical Reader. New York: New, 1999. Print.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.Posted March 2014