Itineraries

A week before the MLA 2014 Presidential Forum on the public humanities in vulnerable times, I walked through the corridors of the University of Michigan Department of English Language and Literature, reading doors.

I had decided not to look at my most public projects but to undertake instead a reading of the departmental space on campus, a space to which I have had the longest association. Ours is a big-tent English department in a passionately interdisciplinary and historically decentralized public research university. Many members of the department (myself included) are jointly appointed in at least one other department. Our ways of being public are as varied as our multiple affiliations. I do not see us as representative of some typical way of being an English department, though no doubt we are. Rather, I see this forum as an opportunity to argue that every department, in its own fashion, should think about how it represents (in all senses of that word) the public humanities.

My first step toward a closer look, with collaborators, at more departments is impressionistic. It is a preliminary reading of a few visual signifiers, in the department, of the professional itineraries of faculty members and students outside the department. It is an effort to bring public practices to the forefront of departmental conversations, so that we can ponder collectively the public activities, purposes, and alliances that keep many of us moving along a continuous figure eight that loops between on- and off-campus spaces.

In advance of the forum, my fellow panelists and I were invited by Marianne Hirsch and Laura Wexler to speak to several questions, including the following:

- What is the public face of the humanities, and how can humanities scholarship be publicly shared in vulnerable times?

- Why do you do the work you do? How do you think about the public?

- What are the opportunities that living in vulnerable times provides for the future study and practice of public humanities?

The charge to the panelists tilted toward the public humanities imagined as scholars addressing audiences of nonacademic strangers through public lectures and nonspecialist media. I do not address here the question of the humanities’ public face manifest in acts of public explanation.

By way of contrast and supplementation, I look at a way of doing the humanities across sectors. By “across sectors,” I mean activities that involve relations between academic institutions and private, public, or not-for-profit organizations. The shorthand phrase is “campus-community partnerships,” through collaborative public engagement situated, on the academic end, in courses, projects, or programs. The kind of work I am referring to is not generally about the humanities. In other words, its primary goal is not appreciation of and involvement in the humanities per se.

For me, public humanities projects have been about the power of words: multiple uses of artist statements composed by printmakers in Johannesburg; the Harriet Wilson Project in Milford, New Hampshire; the poetry of everyday life in third-graders’ close encounters with our local watershed; the Detroit arrival stories narrated by high school poets and their parents in the intergenerational Boomtown project of the Inside/Out Literary Arts Project; and the exploration with Sekou Sundiata, a poet and theater artist, of “the soul of America” in post-9/11 arts-mediated gatherings and a touring performance work.

My connection to the public humanities is grounded more in the public work of humanists, therefore, than in the public explanation of the humanities. The most compelling artifacts that I found on the department’s doors presented themselves as vocational statements—”callings to careers” (Boyte) in which “personal flourishing and broad public purposes are intertwined” (Proposal).

There is a lot to like in Christopher Newfield’s approach, which values public explanation in the working contexts of organizations, institutions, and “individuals in groups” who are committed to “cultural development.” For Newfield, cultural development fosters “creative capabilities, including the capability to originate, to cooperate, to improvise, to problem-solve.” He glosses cultural development in a way that offers a starting point for reflection on the public humanities in literary and cultural studies departments. The “interpersonal and cross-cultural” literacies he values include “crucial abilities in conflict resolution and the refusal of scapegoating, projection, and other psychological habits that escalate difference into conflict” and “radical, indigenous, and experimental understandings of the way individuals in groups create value and new possibilities together.”

I recently argued that we could understand this organizational, relational, and constructive type of public humanities in terms of how it mediates “between one place and another and between one kind of practice and another” (294). I suggested that this area of the humanities should be defined positionally as well as in terms of theories, methodologies, and content. From the standpoint of the positional humanist, then, what do I see in my tour of departmental doors? What do they tell us about the presence and absence of the public humanities in departmental life?

Doors

Philologists for Peace: Individual Statements

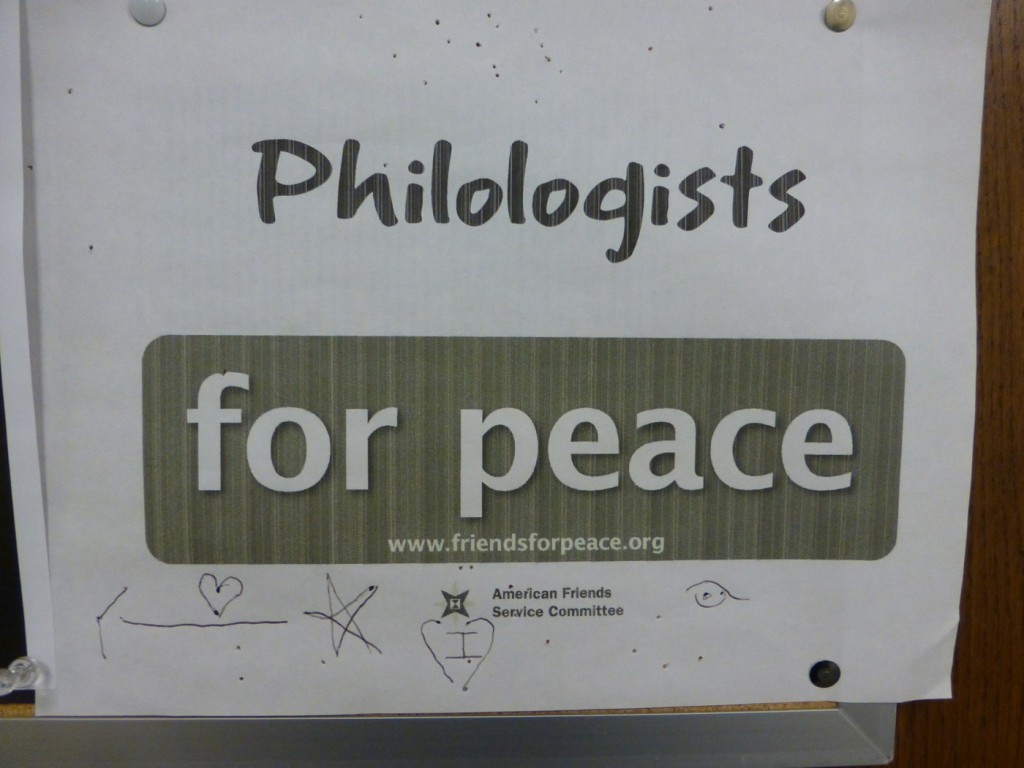

Karla Taylor, a Chaucerian, posts this sign on her door: “Philologists for Peace: www.friendsforpiece.org: American Friends Service Committee.”

In response to my e-mail query, she explained the post-9/11 context of this sign, “a pop-up Quaker organization”:

“Friends for Peace” . . . created a template sign that people could adapt for peace marches during the Iraq war. . . . People would carry signs “Grandmothers for Peace” or “Dentists for Peace.” I originally made the “Philologists for Peace” for our front window at home, and everyone in the neighborhood asked for the link so they could make their own. We had “Schoolteachers for Peace,” “Anthropologists for Peace,” and several others I no longer remember. (“Re: ‘Philologists’” [17 May])

This sign traveled from her office (where her role as philologist would seem to be located) to her residence. The visible claim of a connection between one’s profession and one’s politics spread as neighbors publicized their work identities in their front windows. The signage then migrated back (as it were) from home to office, when it ended up on Taylor’s office door.

The smile this sign induces has to do with the universal accessibility of “peace” juxtaposed with a member of the quintessential academic insider group “philologist.” (In a follow-up e-mail, Taylor remarked of the sign, “More people asked me ‘What’s a philologist?’ than any time before or since!” [“Re: ‘Philologists’” (19 May). Its most interesting feature is the use of the plural—“Philologists for Peace”—pointing to a small network of academic humanists who see themselves as intermediaries among several publicly significant arenas: the department, the neighborhood, and the antiwar march.

This hallway statement does not refer to public intellectualism per se or to a publicly engaged teaching or research project. Rather it asserts the meaningfulness of a declared work identity as a position from which a person speaks in protest or dialogue. Clearly, one function of the office door is to enact the tricky relation among the personal, the professional, and the political.

Areas of Study

Through that virtual front door, the department’s Web site, faculty pages point to other kinds of signage. The world enters the department’s official online discourse as content, the subject matter of “texts in their infinite variety”:

Our mission as educators is to enable students to become the finest readers and writers of literary texts that they can be. Because those texts in their infinite variety take as their subjects our fellow humans, our histories, and our cultures, we aim in effect to equip our students both to read the world, and write the future, with subtlety, acumen and precision. (“U-M English Mission Statement”)

There is no institutional reference to the public humanities on the department’s home page. I suspect that there is none on the home pages of most English departments. Likewise, there is no departmental area of study on the public humanities. But other terms point to what public humanities might mean for us.

Megan Sweeney is one of several members of the department who use ethnographic methods. This approach is evident in her books Reading Is My Window: Books and the Art of Reading in Women’s Prisons and its companion edited volume, The Story within Us: Women Prisoners Reflect on Reading (“Profile: Megan Sweeney”). Ruby Tapia’s piece in the department’s newsletter points to her coedited Interrupted Life: Experiences of Incarcerated Women in the United States, a volume that covers advocacy on a number of human rights and policy issues, activist interventions, life writing, and research, including participatory action research (“Ruby Tapia”).

E. J. Westlake, a colleague in English and in theatre studies whose scholarship focuses on nationalist performance in Nicaragua, also uses ethnographic methods. Her stated interests include “public art, community-based theatre, pedagogy, and the interplay between public identity, political discourse, and performance narrative.” Previously, she worked in Portland, Oregon, as the cofounder and manager of Stark Raving Theatre. Like Sweeney, but in a different way, Westlake commutes between sites of cultural production as she “continues to write and adapt plays, including plays for young performers” (“E. J. Westlake”).

Following that keyword, performance, through these digital doorways takes us to Petra Kuppers’s faculty page and to a different set of methodologies and organizational relations. These too are shaped by the figure eight of cross-sectoral cultural production. Her most recent book is Disability Culture and Community Performance. Her list of area keywords includes the following terms: performance studies, disability studies, dance studies, community arts, ecology and performance/art practice, contemporary poetry, and indigenous studies or decolonizing methodologies (“Profile: Petra Kuppers”).

A colleague in the area of disability studies, Melanie Yergeau, concludes her contribution to the department’s newsletter by explaining her “double life as a disability rights activist” through the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network (“Melanie Yergeau”). Michael Awkward writes about race and cultural controversies. Sidonie Smith is coauthor, with Kay Schaffer, of Human Rights and Narrated Lives: The Ethics of Recognition. I could go on.

These self-portraits offer rich evidence of public humanities practices that we habitually call something else: life writing, digital culture, exhibition, performance, advocacy, documentary, ethnography. Even a small sampling of the available stories reveals a strong methodological flow between literary and cultural studies, on the one hand, and social movements, the arts, public history, and museum and memory studies, on the other.

For Credit

Alisse Portnoy displays on her office door a course description for her winter 2014 class (English 303) Rhetorical Activism and U.S. Civil Rights Movements.1 The course description itself is a rhetorical act of inclusion: “We welcome non-English concentrators” as well as majors, “people with backgrounds in politics” as well those fulfilling the college’s race and ethnicity or humanities requirements or the department’s requirement for a course on new traditions:

Language matters. . . . [In] U.S. history, and right now, around the world, freedom of speech costs people their freedom, their livelihood, and sometimes their lives. Yet it remains the best path for sociopolitical change. Why is that the case, and how does that work? We’ll study key texts in U.S. black freedom, women’s liberation, and gay rights movements to figure it out. How do people accomplish extraordinary things by speaking up and speaking out? What does it mean to move people to act—discursively? How does language define, normalize, sustain, reform, and even revolutionize the worlds in which we live?

References to the 2012 presidential campaign and to “sociopolitical change” that is happening “right now” do more than demonstrate the applicability of past to present. Portnoy seeks to convey to students the possibility of confidence in their own public agency through discursive action. Even though this class is not community-based, it is public.

In 2008, Craig Calhoun, then president of the Social Science Research Council, saw a “change in the zeitgeist, revealed in the sense of making things, this excitement around making and building institutions, rather than only commenting on the institutions.” He concluded, “You have a lot of the smartest young people trying to build something, and . . . that carries over to academia, where people are saying, ‘I want to do that. I want to create’” (qtd. in Ellison and Eatman viii–ix).

What can students do with their rhetorical activism? My tour of the corridors did turn up evidence of the “excitement” that Calhoun noted. The department acknowledges student interest in socially consequential learning. Outside the door to the main office, a bin labeled “Internship Credit” contains copies of a memo on managing the administrative side of internships:

Occasionally a student will have an opportunity to work with a company or an institution (paid or unpaid) as an intern. . . . Many English majors have found positions applicable to the major at magazines, newspapers, radio/television stations, law and public service offices. . . . Please read the following requirements and stipulations.

That internships for students are a top priority of the department for the university’s current capital campaign is an indication of the growing emphasis on engaged learning campus-wide. But the language of the memo diminishes the emphasis. It suggests that “occasionally” the unusually enterprising student “will have an opportunity” for an internship. The assumption is that this position will be “found” by the student herself or himself without guidance or provision by the department. It is true that unpaid, credit-bearing internships are a problem for colleges.2 But I still want to register the contrast between the lively celebration of student agency in Portnoy’s course description and the regrettably neutral tone in which the memo characterizes internships—neutral at a time when English majors everywhere are hustling to find internships relevant to the major in organizations vital to public culture, public policy, and community development, including the “magazines, newspapers, radio/television stations, law and public service offices” referenced in the memo. In this memo, student choice, not departmental encouragement, drives internships. The department allows that choice but does not integrate it into the curriculum.

As I pass by other hallway postings, it becomes clear that the memo’s public service agencies are already connected to some courses. William (Buzz) Alexander’s door displays a flier for a fund-raising auction to benefit the Nineteenth Annual Exhibition of Art by Michigan Prisoners, run by the Prison Creative Arts Project (PCAP), which Alexander founded in 1990 (see “Affiliated Courses”). Long based in the English department, PCAP is now a program of the Residential College, which is becoming the center for public engagement programs in the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts (LSA). The annual exhibition is one of a suite of PCAP programs operating in corrections institutions throughout the state.

Faculty members in several units teach PCAP courses. In the English department, these courses reflect the program’s goal of sustaining a “creative hub” that connects and supports participants: Revision in Theory and Practice (with the Michigan Review of Prisoner Creative Writing), the Atonement Project (in which students create “artistic products…as a means for starting conversations about reconciliation and atonement”), and the Portfolio Project (in which students facilitate the creation of arts portfolios by incarcerated youth) (“Affiliated Courses”).

The poster for the benefit auction asserts the value of both course-based engagement and iterative programs like the annual juried exhibition and an annual cycle of workshops, readings, performances, and symposia. This yearly strategy resists the episodic one-off projects of many community service-learning courses (including a few of my own) while valuing improvisation. PCAP courses have provided generations of interested students with an unofficial course sequence—a developmental learning experience. For two decades, it was our first and, for a long time, our only model for connecting a set of regularly offered courses to specific external partners: corrections facilities. How will it inform our understanding of the public humanities going forward?

Departments

The system-wide Office of Public Engagement at the University of Minnesota supports an Engaged Department Grant Initiative designed to further “the integration of public engagement into the programmatic features of the department,” research and teaching (“Engaged Department Grant Program”). Other colleges and universities offer similar programs, some of which also sponsor an institute attended by teams from departments funded in a given cycle. This is an excellent model, not least because of the conversations that necessarily precede the collective decision to write and submit a proposal. Funding incentives stimulate deliberative occasions, times when the department becomes a commons.

But we can have these discussions without such incentives, in faculty meetings, annual retreats, or symposia. In these settings, we can explore how exactly the public humanities becomes visible and audible in our departments—how it enters into departmental life. For example, my department could reflect on the gap, discussed above, between the representation of administrative process on the internship credit form and the public practices evident on faculty doors. Or the difference between the emphasis on traditional forms of literary studies in parts of the department’s mission statement and the declarative doorways of colleagues who are working outside that framework. Are these new areas moving more to the foreground? Should the mission statement highlight public-political rhetoric or collaborative performance or participatory off-site learning? At every level of higher education, discussions of the public mission of the university are under way. So are debates about the humanities. What about the public mission of the humanities department? Is it reasonable to raise this question? Is it possible to answer it?

What other questions would arise at an annual meeting convened to consider, say, an English department as a commons? Here are a dozen possible ones: What are the growing tips of publicly engaged teaching and scholarship in our respective areas? How do we read the field right now? What vocabularies are available to us as we discuss these matters? How can our departmental commitments to diversity and inclusion enhance our capacity to learn from and partner effectively with communities, and vice versa? If we riff on public history, what would public literary history look like in our settings? Do our community-based courses form a sequence? Is it time for a minor in the public humanities, a minor in literature and society, a minor in digital culture and social change? Have we moved beyond the disempowering assumptions of community service construed as giving (Robinson)?3 Is there pressure for public humanities options in the graduate program? Are tenure policies adequate to the complex projects pursued by faculty members, that complexity including the mix of texts and artifacts that projects yield? If faculty members and students are pursuing publicly engaged research and learning outside the department, through centers and interdisciplinary academic units, is the department impoverished or enriched by this pursuit? Should concerted publicly engaged teaching, scholarship, and community development focus on a specific location—for us, at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor?

The answers to these twelve questions matter. So, too, does the proposed occasion itself: a yearly intergenerational exchange, inclusive of many constituencies, that can alter the debate on the humanities in vulnerable times, one department at a time.

Notes

I am indebted to my colleagues in the University of Michigan Department of English Language and Literature whose pathways to the public humanities stimulated these reflections: William (Buzz) Alexander, Michael Awkward, Petra Kuppers, Alisse Portnoy, Michael Schoenfeldt, Sidonie Smith, Megan Sweeney, Ruby Tapia, Karla Taylor, Theresa Tinkle, E. J. Westlake, and Melanie Yergeau. And thanks to Sarah Robbins for her discerning response to an earlier draft of this essay.

- Down the hall, on Alan Wald’s door, a poster recalls another act of rhetorical activism: the 2012 conference The Port Huron Statement in Its Time and Ours: “Voices of protest that shook the sixties. Activists, organizers, and visions of change / Remembered now, in times of crisis and dissent.” ↩

- The debate over unpaid internships concerns the question of whether colleges should grant academic credit for unremunerated internships, which are construed in the courts and in the press either as career-building summer jobs that only wealthy students can afford or as experiential learning that involves reflection and advising (McDermott). ↩

- “[S]tudents sometimes see service as an alternative to politics—a way of performing good works without the hard work of negotiating across differences or bureaucratic institutions, which suggests that service experience could actually undermine students’ sense of civic agency” (Robinson 20). ↩

Works Cited

“Affiliated Courses”. PCAP: The Prison Creative Arts Project. U of Michigan, n.d. Web. 7 Oct. 2014. <http://www.lsa.umich.edu/pcap/whatwedo/affiliatedcourses>.

Boyte, Harry C. “Reinventing Citizenship as Public Work.” Democracy’s Education: A Symposium on Power, Public Work, and the Meaning of Citizenship. Ed. Boyte. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, forthcoming.

“E. J. Westlake.” U-M School of Music, Theatre and Dance. U of Michigan, 2006–2014. Web. 6 Oct. 2014. <http://www.music.umich.edu/faculty_staff/bio.php?u=jewestla>.

Ellison, Julie. “Guest Column: The New Public Humanists.” PMLA 128.2 (2013): 289–98. Print.

Ellison, Julie, and Timothy K. Eatman. Scholarship in Public: Knowledge Creation and Tenure Policy in the Engaged University. Syracuse: Imagining Amer., 2008. Print.

“Engaged Department Grant Program.” Office for Public Engagement. U of Minnesota, 15 Oct. 2012. Web. 26 May 2014.

McDermott, Casey. “Colleges Draw Criticism for Their Role in Fostering Unpaid Internships.” Chronicle of Higher Education. Chronicle of Higher Educ., 24 June 2013. Web. 26 May 2014.

“Melanie Yergeau.” 2011 Alumni Newsletter. Department of English Language and Literature. U of Michigan, 2011. Web. 26 May 2014. <http://www.lsa.umich.edu/english/alumni/newsletter/newletter11-12_web.pdf>.

Newfield, Christopher. “Reflections on the Significance of the Public University: Interview with Christopher Newfield.” Public Intellectuals Project. Public Intellectuals Project, 26 Nov. 2011. Web. 26 May 2014.

“Profile: Megan Sweeney.” Department of English Language and Literature. U of Michigan, 2009. Web. 6 Oct. 2014. <http://www.lsa.umich.edu/english/people/profile.asp?ID=1035>.

“Profile: Petra Kuppers.” Department of English Language and Literature. U of Michigan, 2009. Web. 6 Oct. 2014. <http://www.lsa.umich.edu/english/people/profile.asp?ID=1244>.

Proposal for New Academic Plan. Northern Arizona University. Northern Arizona U, n.d. Web. 26 May 2014. <http://www4.nau.edu/avpaa/UCC-E13-14/2_102913/CivicEngMinor.pdf>.

Robinson, Alexandra. “Living Democracy: From Service Learning to Political Engagement.” Educating for Democracy. Issue of Connections (2012): 20–23. Web. 26 May 2014.

“Ruby Tapia.” 2011 Alumni Newsletter. Department of English Language and Literature. U of Michigan, 2011. Web. 26 May 2014. <http://www.lsa.umich.edu/english/alumni/newsletter/newletter11-12_web.pdf>.

Taylor, Karla. “Re: ‘Philologists for Peace.’” Message to the author. 17 May 2014. E-mail.

———. “Re: ‘Philologists for Peace.’” Message to the author. 19 May 2014. E-mail.

“U-M English Mission Statement.” Department of English Language and Literature. U of Michigan, 2009. Web. 6 Oct. 2014.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.Posted November 2014