There had been dissenting voices, the most notable that of the labor economist Allan M. Cartter, who was vice president of the American Council on Education from 1963 to 1966 and chancellor and vice president of New York University from 1966 to 1972. In a paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Statistical Association in 1965, Cartter examined the models that had been used to develop the projections of the 1950s and found them to be “poor predictors of actual developments” (26). Looked at in the light of what had happened over the years between 1954 and 1965, the models overstated the rate at which doctoral-level faculty would need to be replaced and understated the rate at which higher education would succeed in expanding doctoral education and the pool of candidates completing terminal degrees. Several years later, in a paper contributed to a 1969 compendium on the economics and financing of higher education prepared for the Joint Economic Committee of Congress, Cartter and Robert L. Farrell, of the Smithsonian Institution, could affirm even more strongly how wrong the projections of dire shortages—“4 or 5 teacher openings for every PhD available” (358)—had turned out to be. “We can look forward to the 1970s with confidence that there will be an adequate supply of available manpower to meet most critical needs in teaching, research, and specialized employment fields. Whereas for the last decade we have needed to channel about half of all persons receiving the doctorate into college teaching to maintain the quality of our staffs, in the 1970s less than a third will be required, and fifteen years from now it may require only one in five” (357).

The record of PhD completions in English and other modern languages is illustrative. In 1958, the federal government reported a total of 596 modern language doctorates on its annual census of new doctorate recipients, the Survey of Earned Doctorates (SED)—439 in English and 157 in other language and literature fields (classics excluded). Thirteen years later, in 1970, the fields’ doctoral programs, expanded in size and enlarged in number, awarded doctorates to 2,012 graduates, well over triple the number of 1958 (1,365 graduates in English and 647 in other modern languages). Through the 1960s, as doctoral programs were accelerating the production of modern language PhDs by more than 10% per year, on average, the MLA’s role continued to be helping departments identify qualified candidates for the many faculty positions they were desperately seeking to fill (MLA Office of Research 9 [fig. 3], 11 [fig. 5]). Each fall the association solicited vita sheets from students who had completed or were about to complete their doctoral programs and who were planning to attend the MLA convention (fig. 1). The vita sheets were gathered into binders for department chairs to review on-site at the convention, so that hiring departments could arrange convention interviews with candidates whose qualifications met their needs. At the 1969 convention, this system was overwhelmed by the large and still growing wave of PhDs and PhD candidates who arrived in Denver to compete for what had suddenly become a contracting number of professorial positions.

Fig. 1. A sample vita sheet for the 1967 MLA convention (Vacancies in College and University Departments of English for Fall 1968, vol. 1, no. 1, Nov. 1967, p. v, www.mla.org/content/download/10442/233861).↩

The shock of the 1969 convention is apparent in the consternation and spreading panic that rippled out from this abrupt reversal of fortune, as the 1970 report of the Commission to Study the Job Market appointed to respond to “what went wrong” in Denver suggests (Orr, 1192–93). One result was the reconstruction of the MLA’s job-related services. Beginning in the mid-1960s, the ADE and ADFL had initiated lists of “vacancies in college and university departments” to give department chairs who were experiencing difficulty filling faculty positions a way to bring the openings on their faculties to the attention of candidates (fig. 2). In October 1971, the vacancies lists were replaced by the Job Information List, which was conceived as a comprehensive survey and compilation of statements from departments about their hiring plans (fig. 3). Along with announcements of positions that were available and for which departments were seeking candidates, the new lists initially included statements that “no vacancies are anticipated or likely.” The idea was to give a statistical overview of the academic job market, direct job seekers to the available positions they were realistically qualified to apply for, and stem the flood of inquiry letters panicked candidates were blindly mailing to dozens, sometimes hundreds, of departments. The first English and foreign language lists note that statements were received from 55% of the English departments and 50% of the foreign language departments the MLA contacted; many entries consist of the short statement “no information received by press time.”

Fig. 2. Cover of the November 1967 issue of the ADE and MLA’s Vacancies in College and University Departments of English for Fall 1968, the precursor to the JIL.↩

Fig. 3. Cover of the October 1971 issue of the English edition of the JIL (Modern Language Association, www.mla.org/content/download/10463/233987).↩

The trauma of 1969 has had a long afterlife in the profession’s collective psyche. Particularly sensitive is the sore spot touched whenever questions arise of just what occupational and career possibilities doctoral study in language and literature can lead to. What career options can doctorate recipients and their programs embrace as legitimate? What career outcomes might programs and graduates celebrate as shining examples of their success? Which do they mourn as the depressing signs of their failure? On this point, Cartter and Farrell concluded their contribution to the 1969 compendium by sounding a highly optimistic note:

The nation is accomplishing a goal that was thought unattainable a few years ago, by virtue of a strong partnership among public and private agencies. If the Congress had not acted with determination in the 1958–65 years to support graduate education, and if the States and the private universities had not been willing to invest untold millions in what they believed to be the highest priority task in the nation, the goal of insuring an adequate supply of the best brains and talents for college teaching, research, government and industrial service would not have been achieved prior to the 1980s. . . .

The projections of doctoral supply indicate that a rapidly increasing proportion of the total will be available for nonacademic forms of employment—in government, industry, and nonprofit agencies. This can only be viewed with satisfaction, as a mark that this nation has met its critical priority needs and can now begin to utilize this talent in a broader array of challenging tasks. If we are to revitalize the cities, improve the public schools, conquer pollution, improve health standards, explore outer space, and a hundred other tasks claiming our attention and energies, our strongest asset will be an expanding reservoir of highly trained talent. (374)

Citing this passage, the 1970 MLA report redirected Cartter and Farrell’s optimism to a determinedly pessimistic and depressed conclusion:

Unfortunately one of Cartter’s and Farrell’s conclusions has grim repercussions for us. “The projections of doctoral supply indicate that a rapidly increasing proportion of the total will be available for nonacademic forms of employment—. . .” Figures in our disciplines indicate that academic work employs over 90% of us; that is not because we choose it, but because that’s all there is to do. If more of us become available for nonacademic work, we won’t be using our degrees. (Orr 1187)

With this formulation, the commission’s report elevated appointment as a postsecondary faculty member into a normative marker as the sole employment outcome the fields’ doctoral programs and their graduates could—even should—possibly regard as legitimate or acceptable. The passage at once reflects and speaks to a culture of doctoral study bound to the doxa that only academic work qualifies, or can qualify, as employment appropriate to the doctoral degree; the logic requires all other employment to be by definition underemployment: “we won’t be using our degrees.”

And so prevailing sentiment across the discipline has continued to hold from that day to this. For students pursuing doctoral study in language and literature, a core aspect of acquiring scholarly identity and signaling acculturation into the profession consists of accepting and affirming a largely unspoken tribal understanding that “for us” postsecondary teaching remains “all there is to do,” the sole occupation in which those who complete the ordeal of earning the PhD know they have found suitable work.

The actual placement history, by contrast, points to other possibilities. The first six in the MLA’s series of PhD placement surveys revealed that through the 1970s and early 1980s significant and growing numbers of modern language doctorates were finding their way to professions outside academia. Across the six surveys, conducted between 1977 and 1985, 12.8% of new degree recipients in English, on average, and 17.0% of those in other languages had proceeded to work outside higher education directly after completing doctoral study. Among PhD recipients in languages other than English, the subset finding employment outside the academy immediately after graduate school reached a high point of 20.3%, for graduates who received degrees in 1978–79 (Huber, “MLA’s . . . Latest Foreign Language Findings” 68). Among new doctorate recipients in English, it rose as high as 15.3%, for the 1983–84 cohort (Huber, “MLA’s . . . Latest English Findings” 48). The brief resurgence of tenure-track faculty hiring in the late 1980s reduced the flow of graduates to placements outside higher education. And as employment opportunities in and also beyond academia contracted in the recession of the early 1990s, the postdoctoral fellowship, a negligible feature of the humanities career path up to 1990, started to claim a steadily rising share of placements, increasing, for example, from just 0.9% of English graduates in 1992 to 7.3% in 2010. Over the seven surveys in the placement series that the MLA has fielded since 1990 (the last covering 2009–10 PhD recipients), 7.6% of new PhD recipients in English, on average, and 10.2% of those in other languages have found employment in occupations outside higher education—about half the peak figures of the 1970s and 1980s.1

As a first job placement after graduate school, then, PhD recipients have long gone on to employment beyond academia and postsecondary faculty appointments, albeit on a modest scale and often enough in the face of indifference or even active hostility from the prevailing disciplinary culture. But the historical record of placements immediately after graduate school reveals only one part of the story. A more complete picture emerges when information is added about what happens to degree recipients as they move forward in their careers and working lives. We possess two snapshots of the occupations where modern language PhDs have their primary employment—the 1995 Survey of Humanities Doctorates conducted by the National Research Council as part of the Survey of Doctorate Recipients and a 2014 MLA study of employment outcomes for a sample of individuals who received a modern language PhD between 1996 and 2011. Since 1973, and most recently in 2015, the federally sponsored biennial Survey of Doctorate Recipients (SDR) has canvassed a sample of individuals who have earned a doctorate in engineering; biological, health, and physical sciences; and (but only from 1977 until 1995) the humanities. The SDR explores the demographics and career histories of respondents from the date they receive the degree to age seventy-six. (Supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the humanities participation in the SDR did not survive the reductions in the endowment’s budget in the mid-1990s.) The MLA study took a step toward filling the gap in our knowledge that the loss of the SDR created. With the support of a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the MLA office of research used Internet searches for public information to identify the employment status and occupations in 2013–14 of a random sample of 2,590 cases drawn from a universe of 1996–2011 PhD recipients with Dissertation Abstracts International records in the MLA International Bibliography.

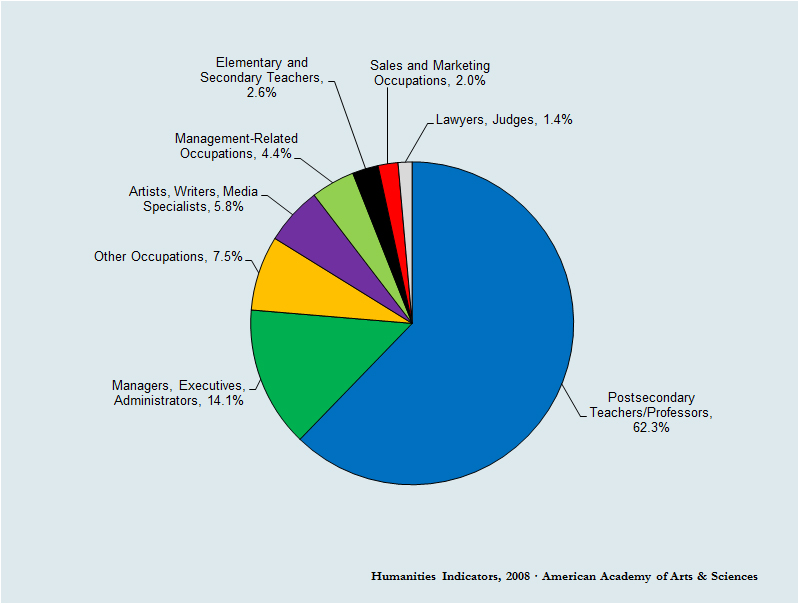

The report on the last SDR to include humanities doctorates, published in 1997, notes that, as of 1995, 60.9% of all employed humanities PhDs had postsecondary teacher and professor as their primary occupation. The other 39.1% were working as managers, executives, and administrators (12.5%); as artists, writers, and media specialists (4.9%); in management-related occupations (4.1%); as elementary and secondary schoolteachers (2.8%); or in other occupational situations (14.7%) (Ingram and Brown 40 [table 12]). The career paths of the subset of these humanities doctorates that held a PhD in English or other modern languages led to what even now may strike many as a surprisingly diverse array of occupations and employment sectors. Careers as postsecondary teachers and professors predominate, but far from exclusively—62.3% of PhDs in English and 64.4% of those in other modern languages held positions as postsecondary teachers in 1995; 78.1% and 77.7%, respectively, were employed by a postsecondary institution (37, 38). Presumably, the difference between the roughly 78% of modern language doctorates employed by postsecondary institutions and the just over 60% employed as postsecondary teachers and professors points to the substantial numbers who held what would later come to be called alt-ac positions in academic institutions but who were categorized as administrators on the 1995 survey.

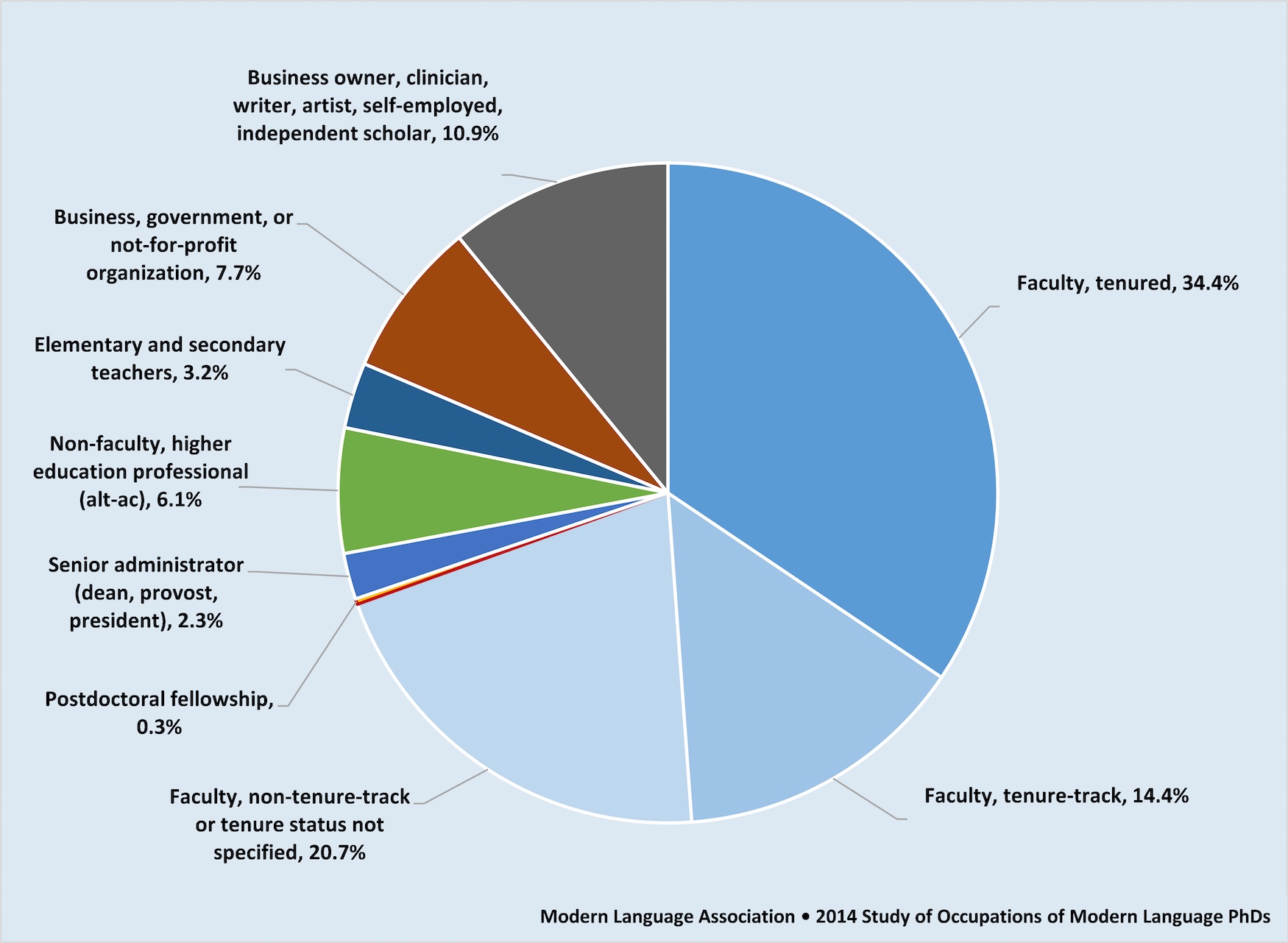

The occupational distribution looks similar in 2014 for the parallel population from the MLA study—employed PhDs who received their terminal degree from a doctoral program in a United States university and who were residing in the United States at the time of data collection. The MLA study found about 70% of modern language PhDs working as postsecondary teachers or professors, compared with from between 62% and 64% in 1995, as reported in the SDR. But an almost identical fraction were employed in higher education, whether in teaching appointments or nonteaching administrative posts—79% in 2014 compared with 78% in 1995.

The Humanities Indicators has compiled findings from the humanities portion of the 1995 SDR, reproduced in figure 4 and figure 5. Figure 6 shows corresponding findings from the 2014 MLA study. Together, the three charts make vividly apparent both the strong orientation toward careers in higher education among modern language doctorates and the diversity of their job outcomes across a spectrum of professional positions, whether as postsecondary faculty members and administrators; secondary and elementary school teachers; or professionals in business, government, and nonprofit organizations.

So the history points to two conclusions. People enter the long and arduous path of doctoral study in the humanities thinking of professorial careers as a primary goal; and those who complete a doctoral program actually find careers in a far broader range of occupations than postsecondary teaching, even if their first job after graduate school is a postsecondary faculty position, on or off the tenure track. The question, then, is not whether doctoral study can lead to careers beyond postsecondary teaching—it already does and has for decades. The question comes down to the view doctoral programs and their inhabitants take of what has long been that simple fact. Do the diverse career paths that PhDs follow inspire an enlarged sense of success and possibility, both for the individual graduate and for the doctoral program and its faculty? Or, as the 1970 MLA report puts the case, are we to resign ourselves to a pessimistic sense that placements and careers other than a career as a scholar-teacher in a tenured faculty appointment signal failure—failure on the part of the individual graduate, of the program and the members of its faculty, and also of the wider profession?

Fig. 4. “Principal Occupations of Employed English Ph.D.’s, 1995” (Humanities Indicators, 2008, www.humanitiesindicators.org/content/indicatordoc.aspx?i=311; fig. III-8d). Basis for percentages: employed PhDs who received their terminal degree from a university in the United States and who were residing in the United States at the time of data collection in 1995.↩

Fig. 5. “Principal Occupations of Employed Modern Languages and Literatures Ph.D.’s, 1995” (Humanities Indicators, 2008, www.humanitiesindicators.org/content/indicatordoc.aspx?i=312; fig. III-8e). Basis for percentages: employed PhDs who received their terminal degree from a university in the United States and who were residing in the United States at the time of data collection in 1995.↩

Fig. 6. “Occupations in 2014 of a Random Sample of Individuals Who Received a PhD in Modern Languages, 1996–2011” (Office of Research, MLA, 2014; unpublished data file). Basis for percentages: 1,969 PhDs who received their terminal degree from a university in the United States and who were employed and residing in the United States at the time of data collection in 2013–14.↩

It is important to increase both public and professional awareness of the actual diversity of humanist career paths, the range of professions where program graduates make their living, and the number of graduates working in those professions. But the placement facts may be of lesser import than the achievement of what has remained an elusive conceptual breakthrough: a robust account of the intellectual capacities and forms of specialized expertise exercised and advanced through humanistic study. To be at all influential, a concept of humanistic expertise needs to command wide recognition, both in public discourse about the humanities and in humanists’ professional discourse about themselves. Correspondent to such an account of humanistic expertise would be the idea of a humanities workforce.2 Humanistic expertise advances as scholarship advances and elaborates its capacities to learn from the objects it studies, whether those objects be the documentary materials of the cultural record or the evanescent performances of social action (Guillory). As a feature of public and professional discourse, the concept of humanistic expertise would mediate between the scholarly research space of academic work and the varied occupational niches connected to and reliant on it, however directly and recognizably or hidden and unacknowledged. In the absence of a concept of humanistic expertise, understanding of the link connecting educational attainment to occupational possibility becomes limited to the PhD as a formal qualification required to compete for a particular job. If a tenure-track appointment in a four-year college or university is the one job for which the PhD is required, career possibilities deemed suitable for those who pursue and attain the degree necessarily contract to the tenure-track appointment in a four-year college or university. The discussion gets stuck at questions like, “But for what jobs (besides a postsecondary faculty position) does someone need to have completed a PhD in literature?” or “What evidence do we have that employers would prefer someone who completed a dissertation and received a PhD to a candidate who holds an MA or BA?”

This reductive logic defines the small box inside which the profession’s discussion of PhD career paths and possibilities has been confined. As a further corollary, widening the career horizon of doctoral programs, their students, and their graduates is frequently understood, or misunderstood, to entail diminishing their humanistic content and intellectual force, substituting preparation for careers apart from scholarship and teaching for the intellectual work necessary to scholarship and teaching. The result would be to turn doctoral study in literature into, for example, a lesser form of preprofessional training in management. Curricular revision of that kind is of course something a doctoral program could decide to pursue. But the reverse is also possible. We can think less in terms of qualifications signaled narrowly by the PhD as an attainment distinct from the MA or the MPhil or BA and focus more on the attributes and expertise developed through advanced humanistic study, whether or not that study leads to completion of the PhD (and hence of a dissertation). What matters is the intellectual work people do in pursuing humanistic study, the powers and capacities they acquire and deepen through that work, and how they carry these forms of humanistic expertise with them into the wider world. At stake are acquisitions of intellect—capacities for observation, description, judgment, analysis, and thinking; acuity in working with language and images; multilingualism; adept cross-cultural competencies that extend across time and geography in their reach—realized through long practice rising to the demands humanistic inquiries make in their distinctive specificity. Gathered under the homogenizing rubric of “transferable skill,” these attainments become far less visible than they need and ought to be. The question of advanced humanistic expertise and its uses in the world of work presents one form of the wider question of the public value of the humanities and humanistic scholarship. Far from pushing programs toward weakening the humanistic content of advanced study, the question of doctoral education and the careers that follow from it should be seized as an opportunity to affirm the social value of advanced study and the humanistic research space.

Notes

Works Cited

Cartter, Allan M. “The Supply of and Demand for College Teachers.” The Journal of Human Resources, vol. 1, no. 1, Summer 1966, pp. 22–38. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/145012.

Cartter, Allan M., and Robert L. Farrell. “Academic Labor Market Projections and the Draft.” The Economics and Financing of Higher Education in the United States: A Compendium of Papers Submitted to the Joint Economic Committee, Congress of the United States, US Government Printing Office, 1969, pp. 357–74, eric.ed.gov/?id=ED052764. ERIC ED052764.

Guillory, John. “Monuments and Documents: Panofsky on the Object of Study in the Humanities.” History of Humanities, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 9–30. University of Chicago Press Journals, www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/684635.

Huber, Bettina J. “The MLA’s 1993–94 Survey of PhD Placement: The Latest English Findings and Trends through Time.” ADE Bulletin, no. 112, Winter 1995, pp. 40–51. Association of Departments of English, ade.mla.org/bulletin/article/ade.112.40.

———. “The MLA’s 1993–94 Survey of PhD Placement: The Latest Foreign Language Findings and Trends through Time.” ADFL Bulletin, vol. 27, no. 3, Spring 1996, pp. 58–77. Association of Departments of Foreign Languages, adfl.mla.org/bulletin/article/adfl.27.3.58.

Ingram, Linda, and Prudence Brown. Humanities Doctorates in the United States: 1995 Profile. The National Academies Press, 1997, www.nap.edu/catalog/5840/humanities-doctorates-in-the-united-states-1995-profile.

Laurence, David. In Progress: The Idea of the Humanities Workforce. Modern Language Association, 2009. Humanities Indicators, archive201406.humanitiesindicators.org/essays/laurence.pdf.

———. “Our PhD Employment Problem, Part 1.” The Trend, MLA, 26 Feb. 2014, mlaresearch.mla.hcommons.org/2014/02/26/our-phd-employment-problem/.

MLA Office of Research. Report on the Survey of Earned Doctorates, 2012–13. MLA, Jan. 2016, www.mla.org/content/download/40535/1747214/rptSurvEarnedDocs12-13.pdf.

Orr, David. “The Job Market in English and Foreign Languages.” PMLA, vol. 85, no. 6, Nov. 1970, pp. 1185–98. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1261477.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.Posted April 2017