Paula M. Krebs

The public humanities represent a capacious category, and these three articles illustrate a range of successful approaches. No matter what the approach, though, public humanities programs benefit the humanities in higher education. Such programs bring attention to the value of what we teach, as illustrated in Bill Nichols’s article about the ways Georgia State is taking language learning beyond campus walls. They extend campus resources to the community to show why funding for public universities is a public—not private—good, as demonstrated in Laura Anh Williams and M. Catherine Jonet’s piece about their popular feminist film festival in New Mexico. And the programs show the value of humanities research for a community’s understanding of itself, as Diane Kelly-Riley does with her work on the history of her Pacific Northwest company town, Potlatch, Idaho, and what happened to the community when its largest employer closed shop.

The more we bring our work to the communities around our campuses, the more our communities will understand the value of what we teach and study. We need the public to understand the value of the humanities—so parents will not be afraid to let students major in our fields, and so legislators will not call for abandoning our disciplines in favor of narrow workforce-preparation degrees. Connecting humanities education to career preparation, as Georgia State does, is a good resolution. But all this outreach work will only be fully embraced when it is fully recognized by institutional reward structures. So the next step is valuing outreach work in retention, promotion, and tenure cases. Share your best practices with us at Profession.

Free and Open to the Public: Film Festival Curation as Public Scholarship

Laura Anh Williams and M. Catherine Jonet

Originally created as an outreach strategy to highlight humanities scholarship and creativity in gender and sexuality studies, the Feminist Border Arts Film Festival (FBAFF) at New Mexico State University (NMSU) has become a continuously expanding endeavor since its inaugural season in 2016. The festival specializes in programming short films (fifteen minutes and under) created by student and professional filmmakers internationally. At its core, FBAFF is dedicated to promoting innovative feminist, LGBTQ+, BIPOC, and socially conscious filmmaking with the intention of circulating underrepresented perspectives, aesthetics, and approaches to contemporary geopolitics (“2019 Feminist Border Arts Film Festival”). In this way FBAFF offers a vital form of public humanities engagement: by circulating ideas through a video art exhibition, public screenings of short films, discussion with invited filmmakers, and our own artistic production decisions—such as curation choices, design elements, and festival-related filmmaking and media promotions.

By focusing on often excluded voices and experiences, FBAFF offers a platform for filmmakers who are committed to exploring nuanced, complex human and global issues.

In New Mexico, borders are everywhere. The state is home to twenty-three sovereign indigenous nations and NMSU is situated less than fifty miles from both El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. We created FBAFF with the goal of highlighting films that interrogate margins, power, and liminal experiences, and the festival creates a space where we can change public understandings of what constitutes powerful and inclusive filmmaking. FBAFF also contributes to the mission of our land grant university: serving the educational needs of New Mexico’s diverse populations. New Mexico is a state that, since 2014, has placed forty-ninth in Education Week’s annual Quality Counts report, which measures factors such as “college and career outcomes, K–12 achievement and school finances” (Burgess); the state also placed forty-ninth (in 2017) and fiftieth (in 2016) for childhood poverty rates (Edge). New Mexico is also a state that is proud of its film industry, nicknamed Tamalewood, and New Mexico has no shortage of industry-focused film festivals with celebrity screenings and VIP after-parties.

In the gulf between these disparate realities of struggle and stardom, FBAFF attempts to intervene. The festival’s venue for artistically driven films goes beyond a pursuit for profit; the films disseminate knowledge about the human experience of precarious subjectivities with which we—and our underrepresented viewing publics—identify. By focusing on often excluded voices and experiences, FBAFF offers a platform for filmmakers who are committed to exploring nuanced, complex human and global issues. In this way, attendees benefit from perspectives different from those in mainstream, studio-driven filmmaking. In return, attendees articulate their own perspectives. During the culminating program of each year’s festival, attendees offer feedback on the festival through an evaluation questionnaire and vote for award recipients in filmmaking categories such as “best in festival.” Audience suggestions help shape and reshape the festival each year—for example, in response to feedback, the festival has gone from two hours to more than fourteen hours of programming in its most recent configuration—and the awards help filmmakers circulate their work to other festivals, seek funding, and work toward getting distribution. Moreover, FBAFF audiences actively participate in the broader cultural conversations that interrogate notions of power, storytelling, and representation both in front of and behind the camera.

Each year FBAFF has grown in new directions. In 2016, with the moral support of our department but few additional resources, our first festival screening took place in a reserved Technology Enhanced Active Learning classroom on campus, with a borrowed popcorn cart. Since that first year, FBAFF has fostered partnerships with NMSU’s Creative Media Institute, whose department head generously donates use of their digital media theater and popcorn cart each year, as well as with the University Art Gallery, whose director worked with us in 2018 to include a one-day screening of video art programming in their main gallery. Now in our fourth year, in addition to expanding our screening programs and continuing the video art exhibition, we have worked to maintain partnerships with filmmakers from prior years. With grant funding from the New Mexico Humanities Council, the Devasthali Family Foundation Fund, and the Southwest and Border Cultures Institute, FBAFF 2019 opened with a filmmaker showcase that featured a screening and roundtable discussion with four writer-directors, documentarians, and animators whose work has been presented at our festival in past years. Seeking out public funding has reinforced our commitment to the festival as an intellectual and creative endeavor with a public practice beyond the classroom and campus. As literary and cultural studies scholars, before FBAFF we had very little experience seeking external funding for our research and creative projects. The evolution and expansion of the film festival, as it has become a more fully realized endeavor, has made seeking out funding a necessity.

B. Ruby Rich describes the independent film festival as “the last refuge of democracy in this increasingly controlled and manacled world of ours, the last place where a true participatory discourse can prevail and where persons of deep-seated convictions and open minds can come to exchange views, surrender control, and be changed forever by what goes by on screen” (165). With FBAFF, we seek not only to expand the work we do as humanities scholars in gender and sexuality studies beyond our classrooms and majors but also to blur the distinction between town and university and create new viewing publics through the shared audience experience.

Before the festival each year, we spend hundreds of hours viewing thousands of submissions, facilitating a deliberative and purposeful curation process, and ordering final selections into a cohesive narrative trajectory for the screening program. Our curating and programming practices are an expression of our intersectional feminist and queer theoretical approaches—committed to interrogations of power, attuned to intersections of identity and difference, and invested in disrupting status quo politics of representation. In curating the festival, we put a wide range of works into conversation with one another to create thematic programs focused on important social issues such as the international refugee crisis or transgender embodiment in film. During the curation process, we weigh how a film fits with or extends the festival’s mission. We also gauge films by their ability to effectively and aesthetically communicate their perspectives to audiences while also being able to work alongside one another to form narrative threads throughout each program.

We embrace Rich’s description of the film festival as “a political intervention into the market monopoly, a counter-offensive of imagination and difference” (164). Our labor is inevitably rendered invisible by the film festival program, and this labor’s impact is difficult to quantify or describe in measurable terms for our annual performance reports. However, selecting, grouping, and assembling the submissions into a cohesive program with a narrative trajectory is itself a form of creative activity and scholarly dissemination. The University Film and Video Association recognizes the intellectual rigor of university-based film festival curation. It states, “university-sponsored film festivals secure niche films that emerge from independent artists. These films represent a valuable addition to the culture of new media and cinema and might not otherwise secure exhibition or dissemination” (UFVA Policy Statement 18). For us, the value of our labor rests in advocating for the social value of art. Against the grain of the commerce-driven entertainment industry, we work to generate and share a program of socially engaged, innovative filmmaking to promote and circulate humanities scholarship with often underrepresented and vulnerable viewing publics.

Works Cited

Burgess, Kim. “Study: NM Ranks 49th in Quality of Education.” Albuquerque Journal, 4 Jan. 2017, www.abqjournal.com/920639/study-nm-ranks-49th-in-quality-of-education.html.

Edge, Sami. “New Mexico No Longer in Last Place on Child Poverty.” Santa Fe New Mexican, 16 Sept. 2018, www.santafenewmexican.com/news/ local_news/ new-mexico-no-longer-in-last-place-on-child-poverty/article_ ef2ffc0a-c7cb-59ee-b7d6-6e668dcc065b.html.

Rich, B. Ruby. “Why Do Film Festivals Matter?” The Film Festival Reader, edited by Dina Iordanova, St. Andrews Film Studies, 2013, pp. 157–65.

“2019 Feminist Border Arts Film Festival.” New Mexico State University Gender & Sexuality Studies, 10 Mar. 2019, genders.nmsu.edu/film-festival/.

UFVA Policy Statement: Evaluation of Creative Activities for Tenure and/or Promotion. University Film and Video Association, July 2018, cdn.ymaws.com/ufva.site-ym.com/resource/resmgr/ufva_tp_policy_statement_jul.pdf.

Company Town Legacy: A Public Humanities Project Exploring Corporate Influences in Rural Idaho

Diane Kelly-Riley

What happens to a company town when the company leaves? This is the central question informing my public humanities project, Company Town Legacy, which focuses on the rural northern Idaho town of Potlatch, once home to the world’s largest white pine mill until the mill closed permanently in 1981 (Kelly-Riley). Company Town Legacy is a university and community partnership that reflects on the legacy of corporate influence and the challenges of economic revitalization, renewal, and restoration in the rural American west. The American west is romanticized and mythologized, but the reality of life in these rural areas is often overlooked or misunderstood.

How Corporations Influence Cities and Towns in the United States

Corporations across the United States influence the daily lives of workers and shape communities—for better or for worse. In New York City, Amazon’s recent proposed headquarters expansion was met with fierce backlash about the public subsidization of corporations and the effect on communities, and Amazon withdrew its proposal (Goodman). These concerns extend to rural areas too. The yogurt company Chobani, for example, established a large production factory in Twin Falls, Idaho, in 2017, where it has been recruiting and supporting refugee workers, largely Muslim, from Iraq, Afghanistan, and sub-Saharan Africa. The community has dealt with ongoing racial and cultural tensions between these new workers and existing community members. And The Washington Post reports that, “across the country, people in meatpacking towns and agricultural areas are wondering whether their communities will hold on to a supply of Hispanic workers and other foreign laborers crucial to those industries” (Harlan). While corporations may initially provide resources and jobs, they also leave behind financial and social damage and consequences for communities once the area is no longer profitable.

The Rise and Fall of Potlatch, Idaho

Many towns in the Pacific Northwest were established by industries—such as logging, mining, aluminum, railroad, and shipping—to serve corporate interests and were purposefully structured to recruit and retain workers at the turn of the twentieth century. The lives of residents were shaped by connections between corporations and local governments that structured everything—employment, health care, shopping, entertainment, education—from cradle to grave. The town now known as Potlatch was established by the Potlatch Corporation in 1905, according to Keith C. Petersen in Company Town: Potlatch, Idaho, and the Potlatch Lumber Company. Potlatch was a desirable location for river-based transport for many industries because the Palouse River flows through the area once indigenous to the Coeur d’Alene and Nez Percé tribes. The Potlatch Corporation built, owned, and ran everything inside the city limits until the early 1950s, when the corporation’s support was no longer sustainable.

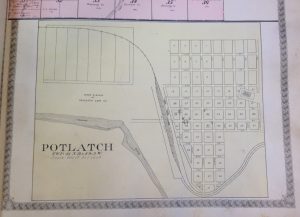

Even after corporations leave, their influence on town and city structures continues to unfold. The blueprints of company towns have been shaped in positive and negative ways. The 1914 plat for Potlatch shows the intentional stratification of residents by social, cultural, and economic status, which built economic disparity into the architecture of the town. Sixth Street was the dividing line between the bosses and the workers. The mill bosses lived in larger, fancier homes on Nob Hill, while the British, German, and Scandinavian immigrant workers lived—literally—below the bosses, in smaller homes north of Sixth Street; Greeks, Italians, Japanese, Chinese, and Irish were forced to live in the adjacent town of Onaway, Idaho, and were excluded from many of the amenities of Potlatch provided by the corporation (fig. 1). The class divide remains present in the geography of today’s Potlatch.

Fig. 1. 1914 Potlatch plat, from the Standard Atlas of Latah County, Idaho; published by Geo. A. Ogle and Co., Chicago, IL, 1914.

Inevitably, companies leave and residents are left to reckon with the lingering structure. The Potlatch Corporation sold its investments in homes and businesses and then withdrew all economic support in 1981 when the mill closed. In the three decades that followed, Potlatch went from a thriving, well-subsidized company town to one in which nearly two-thirds of the population met federal poverty standards. Today for most Potlatch residents, to live in Potlatch means to work elsewhere or to be among the few who are either agricultural landowners or independent logging contractors. The community of Potlatch has struggled to find ways to revitalize its economy.

Company Town Legacy in Potlatch

As an English professor at the University of Idaho who has lived in Potlatch for the past twenty years, I am aware of the overlooked struggles of people in rural company towns whose existence came into being solely to serve corporate interests. My project, Company Town Legacy, partners with the Potlatch Historical Society and the Return to Riverside Music Festival—a revival of a popular music venue in the form of an annual summer western music festival (“History”)1—to reexamine the stories and history of Potlatch as a way to inform our future.

In creating Company Town Legacy, I’ve adopted approaches developed by Vanport Mosaic, a community-driven collective based in Portland, Oregon, that hosts year-round events (Vanport). Vanport Mosaic combines archival work and oral history preservation to produce theatrical and musical performances, documentaries, curated exhibits, and discussions. Extending Vanport Mosaic’s approaches to my teaching and research at the University of Idaho allows me to offer undergraduate and graduate students in English diverse pathways of study involving digital humanities and public engagement and to focus on rural settings.

One part of Company Town Legacy is collecting oral histories of people who attended Riverside Dance Hall. These oral histories were used as centerpiece discussion points for an inaugural event entitled Lager with Loggers, held in April 2019. This event combined humanities-based projects with live music and refreshments to promote the living and relevant role of these histories to community concerns. The goal of Lager with Loggers was to create a framework that memorializes and engages our community in historical events, that uses these remembrances as a way to understand what helped preserve and sustain the community after the Potlatch Corporation left, that highlights contributions of overlooked people and communities in these sustaining efforts, and that facilitates connections between the town and the land grant institution.

Another part of Company Town Legacy is preparing humanities students at the university for roles outside the academy. To this aim, I take advantage of the archives of the Potlatch Historical Society for undergraduate and graduate courses in digital humanities in the English department. Working with these archives gives students hands-on experience with primary source materials and emerging digital tools. Students gain technical experience scanning and recording metadata of images and documents as well as important experience working with members from the community, many of whom were laborers at the mill or worked in some capacity for the Potlatch Corporation. This work is also supported by the University of Idaho Center for Digital Learning and Inquiry’s digital initiatives collection (“Potlatch”). Participating students reflect on the representation of subjects, histories, and lived experience in and around Potlatch. They create several projects, including maps overlaying then-and-now images of Potlatch (Perrault et al.), a timeline of the creation of the town and mill (Dryden), an exploration of the role of women in the lumber camps (Stokes), and documentation of the dangerous practices used by loggers in the forests before the timber got to the mill (Thornton). Students have presented their projects to members of the Potlatch community and have had to consider how to compose their work for multiple audiences—community members who would view the projects in person as well as a broader audience of Web site visitors. These ongoing efforts take the history of an important, but smaller, rural Idaho town and reengage the community and university in ways that revitalize all our work together (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Shannon Dryden, a graduate student in English at the University of Idaho, looks through Potlatch Corp. time cards; 19 Mar. 2018.

Note

1. To address economic challenges, Potlatch established the annual summer western musical festival hearkening back to Riverside Dance Hall, once located along the shores of the Palouse River outside the borders of the dry company town. Johnny Cash even played at Riverside in November 1958, proclaiming, “Potlatch was the toughest damn town I ever played” (“History”). The revival of the music festival provided an opportunity to connect past to present and shed light on the community’s connection to its identity and potential economic restoration.

Works Cited

Dryden, Shannon. “Shaping a Company Town: A Critical Timeline of the Construction of the Potlatch Lumber Mill.” University of Idaho, Spring 2018, sdryden3.wixsite.com/phscompanytown.

Goodman, J. David. “Amazon Pulls out of Planned New York City Headquarters.” The New York Times, 14 Feb. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/02/14/nyregion/amazon-hq2-queens.html.

Harlan, Chico. “In Twin Falls, Idaho, Co-dependency of Whites and Immigrants Faces a Test.” The Washington Post, 16 Nov. 2016, www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/in-twin-falls-idaho-co-dependency-of-whites-and-immigrants-faces-a-test/2016/11/17/f243f0da-ac0f-11e6-a31b-4b6397e625d0_story.html?utm_term=.a6882fe9ff33.

“The History behind Riverside.” Return to Riverside, www.returntoriverside.org/. Accessed 5 May 2019.

Kelly-Riley, Diane. “About Company Town Legacy.” Company Town Legacy, 2019, companytownlegacy.github.io/about/.

Perrault, Joseph et al. “Potlatch, Then and Now.” University of Idaho, omeka.cdil.us/s/then_and_now/page/map. Accessed 5 May 2019.

Petersen, Keith C. Company Town: Potlatch, Idaho, and the Potlatch Lumber Company. Washington State UP, 1987.

“Potlatch Historical Society Collection.” Digital Initiatives / University of Idaho Library, www.lib.uidaho.edu/digital/phs/. Accessed 5 May 2019.

Stokes, Kit. “Flunkies and Loggerettes: Women in the White Pine Forest.” ArcGIS, www.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=cd897eb9ea4c4544af3e1972ec924745. Accessed 5 May 2019.

Thornton, Rob. “Logging the Mountain.” Rob L. Thornton, roblthornton.wixsite.com/logging-the-mountain. Accessed 5 May 2019.

Vanport History. www.vanportmosaic.org/. Accessed 5 May 2019.

Embracing Tentacularity: Outreach, Advocacy, and Rethinking the Ecosystem of Language Departments

William Nichols

When I became chair of the Department of World Languages and Cultures at Georgia State University (GSU) in 2013, the situation in which the department found itself was not unlike that of many other language departments around the country. Severe drops in enrollments, especially for courses at the 3000 and 4000 level, meant not only decreases in credit hour generation but also signified losses in the number of majors (in French, German, and Spanish). Consequently, our department saw increasingly diminished resources that included canceled courses, the termination of academic programs (namely our master of arts in German), and the loss of faculty lines through nonrenewals. Facing low faculty morale and a pervasive feeling of marginalization within the college and university, we began to ask ourselves a series of questions with the hope of recovering a sense of agency: Who are our allies both on campus and off, both academic and nonacademic? Who could be our strongest advocates? What is the value of our academic programs and according to whom? What are the core values of our department? How are our values communicated through our mission and through our curriculum? Are those values in line with the strategic initiatives of the college and university? If we have a mission, do we deliver on it? And, most important, where do we want to go and how do we get there?

. . . we believe that the attention on language proficiency and cultural competency is an issue of social justice . . .

We asked these questions so that we could align the mission of the department with the strategic plans of the college and university, but also so that we could assert the relevance of our programs both in the academic community and in the city of Atlanta. By asserting language proficiency and cultural competence as the core values of our department, we affirm its central role in the internationalization initiatives of the college and university. Moreover, the language department directly serves GSU’s diverse student population by focusing on career opportunities that open with language study while also preparing students to be conscientious global citizens. To thrive, we had to embrace our role as public humanists, preparing students for the world and making sure we were engaged with that world.

New Department Initiatives

As part of that role, our department undertook a rebranding effort that began with the revision of the departmental mission statement and led to changing the name of the department from Modern and Classical Languages to World Languages and Cultures. We have similarly changed the names of concentrations within our major as well as course titles to better communicate their relevance to real-world issues and more overtly demonstrate their connection with other disciplines. In lieu of a university-wide language requirement, the department has sought to incentivize the study of language and culture through the creation of innovative academic programs like the certificate of language ability, a bachelor of interdisciplinary studies in Hispanic media, and soon a workplace intercultural communication certificate. Within our classes, some faculty members are experimenting with a cultural engagement component of the final grade as well as nontraditional assignments that may marry technological skills with language ability and critical thinking, foster collaborative engagement, and better mirror how students might use their language skills and cultural knowledge after graduation. In our department, we have also rethought what recruitment looks like by engaging our alumni and allies in the community who advocate for the relevance of our programs. Through collaborations with the Offices of International Initiatives, Development, Career Services, and other academic units like the School of Hospitality and the Institute of International Business, our department has brought in representatives and recruiters from the CIA, the FBI, Amazon, and Marriott as well as GSU language alumni working at Mercedes-Benz, Delta, Wells Fargo, and the city of Atlanta to connect language ability and cultural competence to a wide array of possible career paths. While many may bemoan the perceived professionalization of academia and complain that our programs, especially those in the languages, have been subsumed into the vocational mind-set of a neoliberal discourse, the department views the focus on careers as a viable way to assert the value of the study of languages and cultures, as well as the humanities more broadly. Moreover, at a university like GSU, a minority-serving institution with a high number of first-generation students and almost sixty percent of its student population on Pell Grants, we believe that the attention on language proficiency and cultural competency is an issue of social justice that empowers students with the necessary skills to engage the world, navigate its complexities, and question the dominant narratives that frame one’s understanding of self and other.

Creating Partnerships

Over the last five years, the Department of World Languages and Cultures has worked closely with other GSU departments within the College of Arts and Sciences, but we have also strengthened our interdisciplinary connections across colleges with departments like economics, public health, hospitality, education, and international business. We have worked closely with the university’s administrative departments as well to promote our department’s curriculum and programming and to combine resources for outreach and fund-raising efforts. As an urban research university in the heart of Atlanta, we believe that a large state institution like GSU must consider itself a public good with strong connections to the community. By looking outside the university, we have sought to create practical opportunities for students to apply their language skills through internships, externships, and service learning. A welcome effect of these community partnerships has been the development of strong allies in the public and private sphere who speak on behalf of our programs. Through connections with K–12 school districts and the Georgia Department of Education—specifically the Office of World Languages and Global Workforce Initiatives, the City of Atlanta, the Metro Atlanta Chamber of Commerce, the World Affairs Council of Atlanta, binational chambers of commerce, the Georgia Department of Economic Development, and others—the department has widened the reach and positive influence of GSU in the Atlanta metro area and in the state; we are bridging the divide between higher education and K–12 and breaking down the walls of the so-called ivory tower.

Innovative Events

Because we believe in the power of the public university to engage society and affect the community, in 2014 the department applied for funding through Title VI in the Department of Education to establish a National Foreign Language Resource Center named the Center for Urban Language Teaching and Research (CULTR; cultr.gsu.edu). GSU’s language resource center is distinct from other such centers in the country because it emphasizes advocacy and career readiness throughout the K–16 continuum. CULTR’s two cornerstone events, the Global Languages Leadership Meeting and World Languages Day, aim to leverage GSU’s location to create a coalition of voices that articulates the value of language ability and cultural competence across the K–16 continuum. The Global Languages Leadership Meeting brings together business and private industry, nonprofit organizations, policy makers and government agencies, and representatives from the K–16 education continuum, all of whom have a vested interest in advocating for language learning. This event aims to forge strategic alliances and collaborations that reinforce the importance of language education.

The other event, World Languages Day, is organized as a global resource fair that invites employers to inform high school and college students about career opportunities available through the study of language and culture. CULTR has brought in partners such as Mercedes-Benz, Porsche, UPS, CNN, the CDC, Grady Hospital, the American Red Cross, the FBI, the CIA, the Peace Corps, the Social Security Administration, the AFL-CIO, and many others. In addition, Mercedes-Benz, McGraw-Hill, Vista Higher Learning, Pearson, Mango Languages, and others have contributed to the event as sponsors. With over a thousand students attending each of the four annual iterations of World Languages Day, this event allows potential employers to inform their future workforce directly, without faculty mediation, about the need for global skills and the opportunities that open with language learning, no matter what the career field. The Global Languages Leadership Meeting and World Languages Day have also established an effective model for advocacy and outreach that other universities have expressed interest in replicating around the country. Both events have propelled GSU to a national stage for language advocacy. In CULTR events, we’ve created connections with organizations like JNCL-NCLIS, ACTFL, and the American Councils through the participation of leading language advocates like Bill Rivers, Marty Abbott, Dan Davidson, and Richard Brecht. In other words, change can and should be implemented on a local level, but never in isolation from the larger context of language programs at the state, regional, and national levels.

I believe it is useful for departments to think of the various initiatives their unit undertakes as part of a fragile ecosystem in which efforts are interconnected within the department but also form part of micro and macro ecosystems. If we work in isolation or in opposition to other units or the community, we endanger our own survival by ignoring the more nuanced ways we may adapt to a changing environment. Rather, language departments should embrace tentacularity by actively seeking collaborations across units and colleges in ways that allow us to insinuate ourselves into other programs, disciplines, and initiatives in clear, convincing ways that assert our relevance but also, and more important, benefit our students. However, while a department may feel a sense of urgency to change, it is important to remember that, in a time of diminished resources, we do not have the luxury of wasting time, money, or energy. By embracing strategic planning and backward design, we can accomplish multiple goals with each initiative. And then we can hope to find our niche in the ecosystem and not only survive but thrive.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.Laura Anh Williams is associate professor of interdisciplinary studies and director of gender and sexuality studies at New Mexico State University, where she teaches courses on social constructions of sex and gender and on feminisms and popular culture. Her research specializations include food studies, contemporary Asian American literature, and critical refugee studies.

M. Catherine Jonet is associate professor of gender and sexuality studies in the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies at New Mexico State University. Her research in contemporary literary and film studies explores how affect and desire are constructed in creative media by queer cultural producers. She is the founder of the Feminist Border Arts Film Festival.

Diane Kelly-Riley is associate professor of English and associate dean for research and faculty affairs at the University of Idaho.

William Nichols is associate professor of Spanish literature and culture at Georgia State University and chair of the Department of World Languages and Cultures. He is the director of the Center for Urban Language Teaching and Research, a Title VI National Foreign Language Resource Center funded through the United States Department of Education. He served as the president of the Association of Departments of Foreign Languages in 2017 and was a member of the ADFL Executive Committee from 2015 to 2018.