A scan of ads for English department chairs posted in recent editions of the MLA Job List (joblist.mla.org) reveals a bevy of necessary qualifications, framed as future-action-oriented calls for leadership. One notes that the successful candidate will be expected to “promote research and teaching excellence [and] support efforts to obtain external research funding.” Another states, “The ideal candidate is an active intellectual leader, adept at building and supporting multi-disciplinary partnerships with a diverse community [and is] knowledgeable in contemporary higher education issues (especially in relation to the humanities).” And still another asks for candidates with “[e]vidence of successful academic program planning, development, and assessment; experience cultivating strategic partnerships, and acquiring grant funding; significant fund-raising experience; a demonstrated commitment to diversity, collaboration and interdisciplinarity, including community and global outreach.”

Clearly, we want and need these skills in our department leaders—but how are we cultivating them on our campuses? Our resistance to seeing leadership roles beyond the department as opportunities rather than burdens limits our knowledge of how leaders—and disciplines—work across our campuses, knowledge we need to possess in order to build strong and forward-thinking units.

Using my experiences as a faculty member who has held major leadership roles outside both the English department and my own area of rhetoric and writing studies, I discuss why we need leaders who have facility with working across academia. To disrupt the accepted and often less-useful internal trajectory to department chair, we must acknowledge the value of external training and mentorship in what leadership work is and can be. We need to engage in what I call disciplinary dexterity, wherein chairs serve from a position of wider understanding of both the general operations of the university and the norms and practices of other fields and disciplines across our campuses. I argue that we should seek out and embrace what interdisciplinary administrative relationships can teach us and recalibrate our views of what a department chair does, is, or should be, as we reconceive upper leadership roles as prerequisite for the position of chair.1 Doing so will allow us to engage more deeply with the broader university to cultivate and diversify our department leaders, which in turn will help us learn valuable strategies for advocating for our colleagues and for the value of our discipline.

Interdisciplinary Leadership; or, How the Rest of the University Lives

As the chair of the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at the Georgia Institute of Technology, which houses an interdisciplinary-minded group of forty-three faculty members, forty-two postdoctoral teaching fellows in writing and communication, and six support staff members, I have taken the administrative pathway less traveled and—with apologies to Frost—it has been the difference. I am a first-generation faculty member who studied creative writing in graduate school but who, over the course of many years and several institutional roles, became a senior scholar in rhetoric and writing studies and a cross-trained academic administrator. As part of my journey through institutional types and geographic regions, I spent seventeen years as a first-year writing program director across three different universities before taking a succession of three extradepartmental leadership positions at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, where I served in two upper-level administrative roles (provost fellow for undergraduate education and associate dean of liberal arts) before serving as chair of a department in a field outside my own (philosophy). I thus took a backward path of sorts toward building a leadership profile. Given this, I want to challenge the typical path that dictates unit-level leadership as the best preparation for higher-level roles, instead arguing that flipping the script may better benefit the chair position and also the pool from which we draw our chairs.

What I learned across my leadership roles at Illinois has informed how I now lead and advocate for faculty members, students, and staff members. Even though at many universities today a typical English or language department contains an array of specializations, meaningful partnerships between humanities and nonhumanities units are not common. Our departments, to benefit their ways of being in the university, have much room to expand their definitions of humanistic work beyond their own borders. Having worked in four traditionally structured university English departments before arriving at Georgia Tech, I have observed that as a field English studies can be provincial and inward facing, not eager to expand its holistic scholarly and pedagogical identities. While scholars such as Gerald Graff, D. G. Myers, Steven Mailloux, and Thomas Miller (Evolution; Formation) have periodically charted English studies’ disciplinary histories, such work typically has reexamined the mix of components that constitute our research and teaching within English studies writ large. And little in these histories speaks to leadership strategies for our current times.2

This historical concern for the integrity of our discipline and for the sanctity of our research and pedagogical methods has meant keeping certain boundaries up to protect our work from dilution. This means when we debate our identity, we tend to turn upon each other rather than seek outside perspectives or partners. We might ask, Does writing and rhetoric studies have a place in departments dominated by literary studies? Do film studies scholars belong in media departments, art departments, or English or language departments? And what is “digital humanities” exactly?3 We are consumed with moving and reassembling our own existing parts, without enough attention paid to how other disciplines are looking across and beyond their borders, especially in their leadership roles and training.

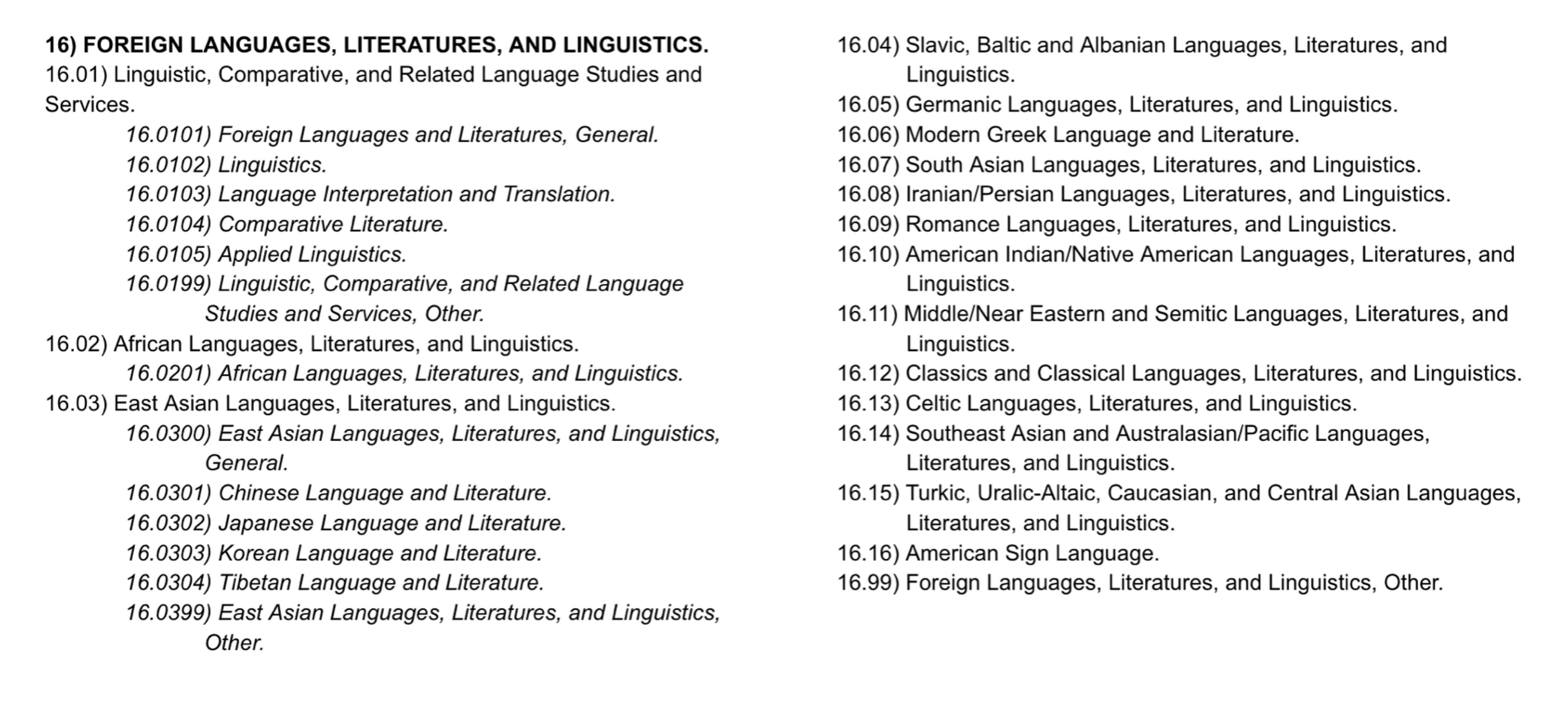

Having served as an associate dean whose portfolio included all undergraduate and graduate curricula across more than thirty departments and programs in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, I can now speak with some authority about how budgets of lab-based units work and how these costs affect both the range of their curricular offerings and who teaches them. I can explain the importance of community-based outreach for language degree programs and the difficulties of staffing and populating classes in lesser-taught languages, including European languages currently dropping off high school course lists (e.g., German). Having chaired a philosophy department, I can differentiate between the core ideological differences in philosophy subfields and how these matter when advertising general education courses in the field. And having worked in a provost’s office as well as a dean’s office, I can identify patterns and trends in enrollments across multiple fields outside the liberal arts, including engineering and business, and how those affect our humanities futures.

There are other service avenues, such as membership on a college or campus-level hiring or promotion and tenure committee, where much can be gleaned about research standards and department operations across the university. Leadership experience outside one’s field helps one become a better chair in three ways: it teaches one to understand the tenets of interdisciplinary and other nonhumanities research as it informs cross-curricular structures, it teaches the principles of such structures in fields as they are articulated outside the humanities, and it reveals the evolution and growth of other disciplines in relation to one’s own. As an associate dean, I came to understand the workings of departments besides English, and I was also able to be at the center of creating cross-disciplinary degree programs among several of them—most valuable, perhaps, when joining computer science with humanities and social science courses for a dual program of study. Programs such as these have the tall order of taking both halves of the degree and making them something new and valuable to students in ways that they could not be when operating as programs independent of each other. Taking that experience into a department chair position provides limitless imagination for what an English degree, and the faculty members teaching in an English department, could do.

Interdisciplinary perspectives gained through other administrative work can influence cluster hiring and strategic planning, each of which requires expertise regarding future programs or growth initiatives that cross disciplinary boundaries. Research-intensive universities in particular emphasize joint appointments for faculty members who can provide new ways of doing research and teaching across units and can contribute to community and industry engagement with scholarship and programming. Had I not watched, while an associate dean, the development of multi-institution, workforce-centered initiatives or reviewed revenue-minded proposals from the humanities, sciences, and social sciences, I would have less understanding of how departments might draw upon these other disciplinary models for both internal and external revenue and expansion. Georgia Tech is undertaking a massive campus initiative in arts programming, Arts@Tech. My experience with imagining cross-disciplinary projects and research has helped me engage in these planning conversations about how our school—with its faculty in media arts—can contribute to this project.

Expanding Pathways to Department Leadership

Every day, department chairs must make micro and macro decisions that affect students and faculty and staff members, decisions that often radiate out to others across campus. Fierce advocacy for one’s own faculty can sometimes fail to take into account the larger ecosystem in which a department lives. Inexperienced chairs do not always recognize that a college’s strength is only as great as the sum of its departments. Leading at the college or campus level frequently teaches us that chairs are not able to be anyone’s advocate in particular but instead must be flexible allies for many. Even when faculty members are willing to chair, they can be quickly disheartened by the day-to-day reality of what such advocacy measures mean. For these faculty members, advisory guides such as Kevin Dettmar’s How to Chair a Department or David Perlmutter’s “Admin 101” columns in The Chronicle of Higher Education (www.chronicle.com/package/admin-101/) are helpful, as are pieces about chairing and academic leadership in the ADE Bulletin (maps.mla.org/Bulletins/ADE-Bulletin). Such publications, like cookbooks, introduce new administrators to the ingredients and techniques that go into successful leadership. Leading outside one’s department, however, provides firsthand experience of working the dinner rush.

As associate dean, I had the insider benefit of observing more than thirty department chairs for four years. I knew their general needs and concerns and what kind of higher-level actions they needed to take in order to keep their units healthy and productive. This helped me when I had to step in as chair of a department experiencing a gap in internal leadership options. I also learned, in the process, how philosophy, a fellow humanities field, has some of the same struggles as English—but not exactly the same. I’ll be drawing on these lessons for years to come.

Of course, it is quite rare to serve as a department chair outside one’s field.4 It is far more common to serve in second-line administrative positions in dean’s and provost’s offices or similar central campus or college units. My experience working in both these positions has taught me that, despite the schism between faculty members and administrators, there is a great deal of collaborative advocacy work happening with faculty members at both these levels. Serving as director of a general education program, for example, can teach one the ins and outs of curricular development from a campus-wide perspective. When I was in that role, I was hiring and in some cases mentoring faculty members to teach small, first-year seminars, while also working with our associate provosts on articulating the effectiveness of this program per its position as our QEP (Quality Enhancement Project) for our institutional reaccreditation.

Department chair work also requires a notion of how bodies that do not intersect with academic programming on a regular basis are still critical to a department’s well-being and stability. As a provost’s fellow, I had the opportunity to work across academic departments and almost every other college on our campus, and I also attended meetings of our Council of Undergraduate Deans, which taught me about admissions and recruitment processes; student services (housing, mental health, scholarships, and funding); and the role of other colleges in undergraduate education. Understanding recruitment, retention, and how students make the choices they do regarding majors (and how they make their decisions to attend one institution over another) is extremely important to knowing how to best grow one’s own programs. These meetings with student support offices also helped me develop important connections and networks that I would draw upon repeatedly in the future.

It is equally important for department chairs to know how shared governance operates beyond the unit level, which can help humanize the work that associate deans and associate provosts do. My experience as an associate dean working with chairs enables me, in my current role as chair, to better understand the fears and knowledge gaps of faculty members as we discuss these same processes, and it gives me strategies for presenting our cases as informed requests designed to benefit the college and campus as a whole.

But perhaps this is the most critical thing I learned while serving in college and university administrative roles before serving as chair: how to understand my department’s position in the larger ecosystem of our university and therefore how to be a champion for everyone in my portfolio, not just my departmental colleagues. This is a hard leap to make. But this is exactly the kind of thinking the best chairs do. We need to think expansively about a greater good for our units and their long-term health. Especially in a school such as the one I lead now, where faculty research specialties include digital media, game studies, film theory and production, theater studies, creative writing, British and American literature, African American studies, and rhetoric and technical communication, among others, one must be ecumenical about advocacy for faculty members, a skill learned best through real-world practice and training at higher levels of academia.

I want to close by encouraging institutions to rethink what leadership profiles—and leaders themselves—can and should look like. This is critically important to the diversity of the faculty members who hold these roles. It’s a fact that women and men of color and white women are underrepresented in academic administration beyond the department level, even as just over half of department chairs are women. Consequently, serving as chair becomes for many the last step in the leadership trajectories within their own departments, which results in a waste of their talent. This is a condition that organizations such as HERS (Higher Education Resource Service [www.hersnetwork.org]) seek to remedy and that external leadership programs—such as the ACC Academic Leaders Network or the Big Ten Academic Alliance Faculty Fellows program (which I participated in at Illinois)—can also help to address. Taking advantage of other national training and mentoring opportunities offered by professional organizations—including, for English studies faculty members, the MLA’s ADE Summer Seminar and MAPS Leadership Institute (www.maps.mla.org/Seminars)—is also critical for new chairs, as well as for other faculty members who may be serving in various departmental leadership positions and whose professional growth can benefit from the MLA’s programming.

Despite professional networking opportunities, faculty members from underrepresented groups who may have great promise for success in other leadership roles may still be burned out, passed over, or never even considered for such roles after serving their own department as chair, all the while being disproportionately assigned service roles. Considering chair candidates who have first done leadership work outside the department, and supporting and mentoring such candidates in their ongoing exploration of other key roles within their institutions, may widen these candidates’ portfolios for future leadership opportunities, including in English studies, while also balancing out who takes up internal and external service roles across campus.

Ultimately, we need informed and generous leaders who have the ability to lead with grace and vision. Leaders with institutional knowledge gained outside their own fields can better respond to the socioeconomic challenges of higher education that ultimately imperil all the humanities. We need to be flexible and open to reconsidering who leads us, how we chart the paths of those who become our leaders, and how much we can all benefit from disciplinary dexterity.

Notes

1 I use the term chair to mean chair or head, as the role may be either in a department (and may even exist side by side within the same institution, as such titles did at my former university, the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign). I do so with the knowledge that department chairs are typically framed as “first among equals” in their level of authority and decision-making, whereas department heads are, in contrast, endowed with veto power that can lead to less collaborative governance. This is an important distinction to make when considering leadership trajectories and pathways, but, for the sake of simplicity of terms, I use chair to stand in for both types of positions.

2 For example, Mailloux’s desire to see rhetorical hermeneutics as the center of our disciplinary practices does not challenge us to look at our own rhetorical practices when interacting with STEM or business disciplines.

3 The NEH’s Office of Digital Humanities, for example, is both expansive and inward facing, in that it “offers grant programs that fund project teams experimenting with digital technologies to develop new methodologies for humanities research, teaching and learning, public engagement, and scholarly communications. ODH funds those studying digital technology from a humanistic perspective and humanists seeking to create digital publications. Another major goal of ODH is to increase capacity of the humanities in applying digital methods” (“Office”).

4 For a good primer on this work, see Buller.

Works Cited

Buller, Jeffrey L. “Chairing a Department in Receivership.” The Department Chair, vol. 27, no. 3, winter 2017, pp. 3–5.

Dettmar, Kevin. How to Chair a Department. Johns Hopkins UP, 2022.

“Fast Facts: Working Women in Academia.” American Association of University Women, www.aauw.org/resources/article/fast-facts-academia/.

Graff, Gerald. Professing Literature: An Institutional History. U of Chicago P, 1987.

Mailloux, Steven. Disciplinary Identities: Rhetorical Paths of English, Speech, and Communication. Modern Language Association, 2006.

Miller, Thomas P. The Evolution of College English: Literacy Studies from the Puritans to the Postmoderns. U of Pittsburgh P, 2011.

———. The Formation of College English: Rhetoric and Belles Lettres in the British Cultural Provinces. U of Pittsburgh P, 1997.

Myers, D. G. The Elephants Teach: Creative Writing since 1880. Prentice Hall, 1995.

“Office of Digital Humanities.” National Endowment for the Humanities, www.neh.gov/divisions/odh.